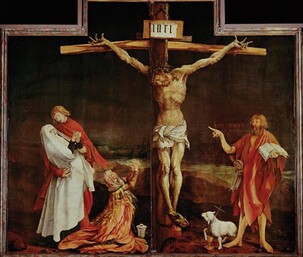

What kind of a crucifixion do we share in on this Good Friday? Is the cross a threat, a judgement, or even a weapon? Is it simply a site and symbol of death and destruction? Or is it a pathway of transformation, for us and for our world? To help us enter it as a pathway of loving transformation, I want to offer a few words around four different images of crucifixion, which may support us in our spiritual journeying today. Each is an image from the suffering of the last century of our modern world. Each, in different ways, represents the crucifixion afresh, and encourages us to know transformation. Let me first however, in introduction, share this great image of the crucifixion from Matthias Grünewald, painted for the Isenheim Altarpiece in the hospital chapel of St Anthony’s monastery. What do you see in it?...

0 Comments

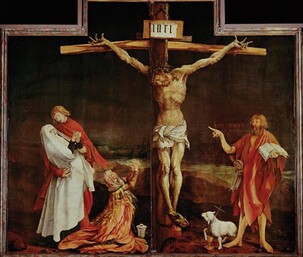

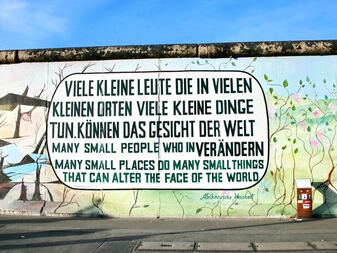

Over the past few years at this service we have tried to focus on those who are presumed to have been present at the last supper of Jesus, but who are invisible in the written accounts – especially those who were not male or in any kind of authority. In a city like Sydney, where the presence of women and sexually and gender diverse people in church leadership is questioned in many quarters, it seems important on this night to say, ‘we were there too’. With this is mind, I looked for images of women at the Last Supper and came upon this one by Jamie Beck. I know too little about her, but Google suggests she is an American photographer and author of the 2022 book An American In Provence. She worked in New York for various prestigious fashion houses before moving to France. During COVID with her husband Kevin Burg she created a series called Isolation Creation sharing one photo per day of the lockdown experience, creating something beautiful positive each day. They were sold with proceeds going to the Foundation for Contemporary Arts COVID19 Emergency Grants Fund...  green heart image by Adithya Vinod on Unsplash green heart image by Adithya Vinod on Unsplash Let us think about three things – about greenery, about the Sydney GreenWay, and about Hildegard’s Latin word ‘viriditas’, meaning greenness or verdancy, that informed out recent entry in the Mardi Gras parade. And let’s keep in the back of our minds a couple of questions – what connects Jesus’s entry into Jerusalem with Extinction Rebellion? Ad what might Hildegard and the GreenWay have to say to the vibrancy and future of the church in our own time?...  image: by Suzanne D.Williams on Unsplash image: by Suzanne D.Williams on Unsplash As a pioneer female priest, one of my wife’s achievements was becoming the first female Rector of the parish of Stanhope, sometimes known as ‘the Queen of Weardale’, high up on the roof of England. She added to a line going back to the year 1200, including some famous names in church history. For whilst, financially and in other ways, ministry in remoter rural areas is challenging today, centuries ago Stanhope was known as the richest living in the north of England for clergy. This was because, way back then, the Church of England drew tithes from local people, who, in the Durham Dales, were chiefly miners and poor farmers and agricultural workers. Not for nothing was this then a significant contributor to the Dales, and County Durham as a whole, becoming strongly Methodist. There is a wonderful little story however about one of my wife’s distinguished predecessors, Joseph Butler. Butler not only became Bishop of Bristol and then of Durham, but, alongside helping to develop 18th century economic theory, he is best known as one of the leading theologians of the day: so much so that the Church of England commemorates him each year on 16 June. Now Butler had been head chaplain to King George II’s wife, Caroline. Some while after he had moved to Stanhope, the Queen therefore asked around the royal court. ‘does anyone know what has happened to Butler? Is he dead?’ ‘No, ma’am’, came back the reply by one in the know, ‘he is not dead, only buried’. ‘Not dead, only buried’: what a wonderful phrase, and one resonating both with our Gospel reading (John 12.20-31), and with our reflections on Celtic Christianity this morning…  image from Museums Victoria on Unsplash image from Museums Victoria on Unsplash What do we make of the serpent of bronze on a pole which we hear about in today’s first reading? And what do we make of Jesus, pictured similarly symbolically in John’s Gospel, as a kind of snake, lifted up on a wooden pole? What do we make of the challenging stories of sin and salvation in our readings this morning?...  scene from Sense8 scene from Sense8 Ecstasy – what does that word mean to you? Ecstasy certainly has many associations! Some of these are deeply sacred, others far more profane. Each however has something in common: they are about standing out: standing out of the ordinary. For in its Greek origins, ecstasy means exactly that. ‘Ek’ means ‘out of’ and ‘stasis’ means ‘standing: hence ‘ek-statis’ – standing out, or away from, the norm. Ecstasy certainly therefore has important philosophical and theological aspects. Take, for example, the queer Cuban American theorist José Esteban Muñoz. I have been thinking about Muñoz because the theme of this year’s Sydney Mardi Gras is ‘Our Future’ and Muñoz gave a great deal of creative thought to imagining more loving futures. For Muñoz suggested that, in contrast to what he called ‘straight time’, at their/our best, queer people live and invite others into what he called ‘ecstatic time’. In other words, instead of living with the ‘normal’ expectations of time and this world, at their/our best, queer people seek to live and reshape this world differently. Instead of our pasts, our presents, and our futures being shaped by our birth families, and by ‘straight’ drives’ for power, children, inheritance, and wealth, at their/our best, queer people seek different kinds of happiness and societal arrangements. For, like other historically marginalised people, queer people have typically been ‘ecstatic’ people. We/they have stood outside of ordinary life and time: which is very much where our two main figures in our biblical story tonight come in – Naomi and Ruth – as striking models of the ‘ecstatic community’ into which God calls us…  a possible future Sydney Town Hall square: artist's impression for City of Sydney a possible future Sydney Town Hall square: artist's impression for City of Sydney ‘People assume’, said the tenth Dr Who,[1] ‘that time is a strict progression of cause to effect, but *actually* from a non-linear, non-subjective viewpoint - it's more like a big ball of wibbly wobbly... time-y wimey... stuff.’ Isn’t that Time Lord right? Time is much more fascinating than we ordinarily think. In today’s Gospel reading we are in this respect challenged deeply. For we are called to choose not only to address what is valuable in past, present and future: in what we call chronological, or measurable, time, deriving from the Greek word ‘chronos’. Rather we are brought face to face with ‘kairos’, another Greek word which means the ‘right or critical’, or meaningful, time. Πεπλήρωται ὁ καιρὸς, are the key words in Greek in Mark chapter 1 verse 15: words often translated as ‘the time has been fulfilled’ (or ‘is ripe’ - for, as the verse continues, ‘the reign of God has drawn near, (repent) turn around and believe the good news’…  on wings of an eagle (image by David Clode on Unsplash) on wings of an eagle (image by David Clode on Unsplash) One ancient way of approaching spirituality, especially in the Orthodox Christian traditions, is to speak of three kinds of birdlife. The first of these, sometimes known as the ‘carnal’ life, is represented by farmyard chooks. These birds peck at the dust, clucking around, and sometimes fighting each other: confined to an enclosure, with their products used by others or being fattened up themselves for slaughter and consumption. The second, sometimes known as the ‘natural’ life, is represented by the rooster. This bird, with more intellectual capacity, is able to rise above, and see beyond, the farmyard dust; and, whilst remaining tied to it, is able to influence and manage aspects of the world of the chooks, at least to a degree. The third bird however is the eagle: who flies free, majestic, and far beyond, the limited horizons of both the chooks and the rooster. Not for nothing has the eagle thus been highly revered, across many cultural and faith traditions, not least among many First Nations peoples: being typically regarded as symbolic of great and deep strength, leadership, and vision. Now, there is of course the danger in such analogies of forms of spiritual elitism, a disregard of the ‘ordinary’, and disdain towards the material. Yet, as we hear Isaiah 40 verses 21-31 today, we are encouraged to be lifted up as ‘on eagle’s wings’. So to what kind of bird do we choose to look? What kind of life do we choose?...  photo by Mark Konig on Unsplash photo by Mark Konig on Unsplash Jeanne d’Arc, the Suffragettes, Mahatma Gandhi, Rosa Parks, the Tent Embassy, Mardi Gras ‘78ers, Tiananmen Square protestors, Peter Tatchell, Bob Brown, the Occupy movement: what do these people have in common?... Would we consider that some, at least, of them have been prophets, or prophetic, in their words and actions? I think there is a case, on at least three grounds: firstly, because they have been typically disturbing to many, and certainly controversial; secondly, because, at the heart of their actions has been a claiming, and transforming, of space reserved, essentially as sacred, by others; and, thirdly, because they ask us to consider what is really true. This is also at the heart of today’s readings, which ask us to reflect on who, and what, is truly prophetic. But let us add some more people into this. How about those who refused to keep to government rules about gathering together and living appropriately during the COVID-19 lockdowns, or the invaders of the Capitol buildings in Washington on 6 January 2021, or the Christian Lives Matters folks who attacked us and others last year? Are they, in their own way, also prophets, or prophetic? After all, they too are typically controversial and disturbing. They also claim and seek to transform spaces which have been defined by others in different ways. And they too ask us to consider what is truly prophetic. For are we just consecrating our particular cultural and political preferences when we say some people or things are prophetic? Or is there something more to it?...  Interwoven Story-telling by Grace Williams (Community & Cultural Resource Officer, Leprena – UAICC Tasmania) Interwoven Story-telling by Grace Williams (Community & Cultural Resource Officer, Leprena – UAICC Tasmania) Twenty years ago now, I was working with the First Nations arm of the National Council of Churches, and was involved in organising a series of events called ‘Hearts are Burning’, each designed to re-ignite positive Christian engagement with First Nations people, and, above all, to help First Nations’ Christian voices to be heard. For the gifts of First Nations’ Christians are vital to any healthy futures for faith in these lands now known as Australia. As one of our keynote speakers back then, the late Aboriginal Bishop Jim Leftwich, would repeatedly, and strikingly, affirm, ‘the mission field has become the mission force.’ In other words, it is those who first received the Gospel in colonial, even imperial, form, who are typically now best equipped to speak genuine ‘good news’ in these lands today. That is part of why we mark today in the Uniting Church as the Aboriginal “Day of Mourning”: both to recognise the continuing impact of past imperial and settler colonial violence and also, crucially, to hear the voice of the Spirit speaking again today through First Nations peoples. It is therefore a huge delight to have Aunty Ali Golding with us again this morning, and, in a few moments, I want to hand over to her to offer her own reflections. For I do not intend to say too much myself this morning, except to share, very briefly, three questions which arise for me from our Gospel, as we mark this Day of Mourning… |

Authors

sermons and reflections from Penny Jones & Josephine Inkpin, a same gender married Anglican clergy couple serving with the Uniting Church in Sydney Archives

June 2024

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed