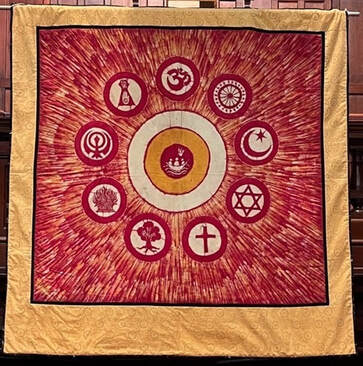

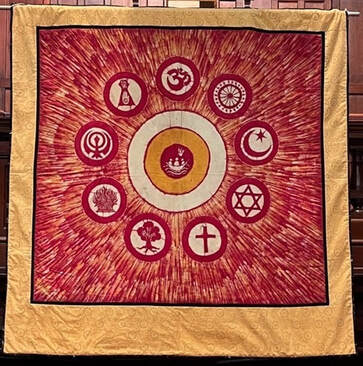

"What's in a name?”, said Juliet: “That which we call a rose. By any other name would smell as sweet.” Shakespeare’s famous lines speak of the power of names and designations. He presents Juliet, on her balcony, musing on the rose as a metaphor, in the context of her love for Romeo and the intense, age-old, conflict between two tribes - the Capulets (Juliet’s mob) and the Montagues (Romeo’s mob). Juliet proclaims that names have no ultimate meaning, other than those which people are willing to give them. As she puts it, in reference to Romeo: “Tis but thy name that is my enemy…. What’s Montague? It is nor hand, nor foot/ Nor arm, nor face. O be some other name/ Belonging to a man.” We do not, says Juliet here, have to be controlled by our names, by our tribes. We can choose how to live with them, and, in love, transcend them. Of course, Shakespeare’s story of the young lovers ends in tragedy. It is challenging to live with, and beyond, our names, our tribal identities. It can bring misunderstanding, opposition, and much worse. Yet is this not the path of true love, in the fullest dimensions of those words? Certainly, as we come today to bless our beautiful new interfaith banner, we do so in awareness of that same call to honour the different names of God, and not to let them control and divide us. For in the depth of all the world’s great wisdom traditions, true love, divine love, is not simply about reaffirming what is valuable in our tribal identities. True love is also about walking paths of inner and outer transformation together…

2 Comments

photo: Rachel Cook on Unsplash photo: Rachel Cook on Unsplash Do you identify with the conversion of Saul, later re-named Paul, which we hear read today? It does not fit us all. Yet it is certainly a striking story, which has powerfully influenced some, especially evangelical, Christian traditions. Indeed, it has sometimes become a classic model for becoming a Christian. It speaks, for example, of a remarkable repentance – or turning around, which is really what repentance means. It speaks of whole-hearted, whole-self transformation of life in Christ; and, above all, it speaks of the transforming power of God’s love and grace. All of this, we may say, are indeed important aspects of Christian Faith, and, as such, the story challenges us, like Saul/Paul, to consider the direction in which we are traveling and what is drawing us and companioning us on the way. All of these things also go to the heart of the sacrament of baptism which we were planning to share this morning. Unfortunately this has had to be postponed due to the baptismal candidate having contracted COVID-19. Nonetheless, it is still worth us reflecting today on the sacraments of baptism and of communion, which we do share together this morning. For, like Saul’s conversion, what do we make of them? How does God’s grace work through them, and in particular moments of our lives?… Good morning! It is a delight to be back here in Pitt Street after several weeks away on personal ‘sorry business’ and study leave. In the context of the continuing pandemic, it has certainly been what some might call an ‘interesting’ time, marking an important watershed in my own life and that of my wider birth family. In offering some reflections today, I would therefore like to begin by expressing my deep gratitude for the many, many. wonderful expressions of support from members of our Pitt Street community, and for the prayers which have been offered. I continue to be so grateful for the gift of loving relationships I am given as part of our life together, and I look forward to their further and deeper unfolding in the days to come. For relationship is such a core element of our lives, and never more important than at times of loss, grief, challenge and growth. As such, it is so absolutely foundational to the Day of Mourning we mark today, as well as to the trials of the pandemic world with which we continue to journey, and the struggles of our own particular lives. In the light of these things, my own recent and continuing journey, and of our readings today, I offer up relationship as one of three words which might be central to our considerations at this time.

One of my favourite contemporary spiritual songs is that which we heard before the beginning of our worship today – ‘I Am Mountain’ by Gungor (see YouTube link above). The lyrics are evocative of both rich ancient understandings and the best insights of modern life and science. They speak of profound presence, of the immanence and transcendence of the divine. They direct us to the heart of the life-giving spirituality of this Season of Creation. For, in Gungor's words, and ancient Christian orthodoxy proclaims, ‘there’s glory’ (‘beauty’ and ‘mystery’) in the dirt.’ As Christian, and other mystics, have affirmed, there’s ‘a universe within the sand, eternity within’ a human being. Often, we may indeed feel ourselves to be ‘wandering in skin and soul/ Searching, longing for a home’. Yet in truth, in memorable phrases, we are invited to see ourselves as:

Momentary carbon stories From the ashes Filled with holy ghost In the face of the climate emergency, we are also called, by ‘the light’, to ‘fight, fight for our lives’ - as we have also explored, particularly in last week’s reflections and discussions. However, above all, we are encouraged to acknowledge more deeply the wonder of the divine existence we share. For we are intimately related to our extraordinary world. All metaphors, as Gungor says, then begin to break down in the face of this astounding mystery and reality, as: Life is here now Breathe it all in Let it all go You are earth and wind… When you step out of your door in the morning, do you feel that you are stepping into a world of wonder in which you are intimately connected? Or, are you simply stepping into mere location? Is it just dead space which you are crossing so that you can get to where you need to go? Or, do you believe you are walking into a living universe? Those are questions which the great spiritual writer John O’Donohue used to ask and they lie right at the heart of the Season of Creation we have just begun this month. For it matters vitally how we view the world and where we locate God in relation to it. So much of our politics, our business and trade activities, and our lifestyles, are affected. If we believe that matter, material existence, doesn’t really matter to God, then we will end up acting in problematic ways. Or, as John O’Donohue used to say, if we do believe that when we step out we are walking into a living universe, then our walk ‘becomes a different thing’. So let us explore some of the theological paths which can underpin more loving and sustainable ways of living together on the Earth…

a shared reflection and invitation by Josephine Inkpin (J) & Penny Jones (P)... (P) We‘ve just heard two different accounts of Jesus’ resurrection, haven’t we?! (Mark 16.1-8 and John 20.1-18) So what we do make of that – and all the other resurrection accounts which cannot be simply conflated? More importantly, what does Resurrection mean to us – to you, to me, to all of us together? That is not a question which can be answered in a few minutes of Reflection. Jo and I have therefore decided to open up a dialogue, which we hope will encourage us all to share in the days ahead. For one thing which is absolutely clear about Jesus’ resurrection of is that it is related through a multiplicity of stories and symbols. These come from different people and biblical outlooks and they thereby also invite us to share our own experiences and insights into Resurrection. For Resurrection is an extraordinary reality we celebrate today. Yet it is not a simple ‘fact’, is it Jo? Isn’t it rather an invitation to see, and travel into, deeper experience, deeper love, and deeper mystery?…  When I was young, parts of the country in which I grew up literally blew away. Living in Lincolnshire, one of England’s greatest agricultural counties, I could see this whenever I traveled. For I grew up as a child at the time of the greatest destruction of England’s hedgerows, many of them very ancient. Indeed, hedgerows are, as the Campaign to Protect Rural England has put it, ‘the most widespread semi-natural habitat in England’, and, more poetically, ‘the vital stitching point in the patchwork quilt of the English countryside’.1 They not only provide character, but essential life to all kinds of creatures, and help protect the soil itself without which there can be no sustainable farming yields. As a child however, I would see such features regularly ripped away, and a vast desert of landscape created, with vital topsoil whirling up in dust storms and carried away. Such soil frequently blinded us, reflecting the blinkered industrialised agricultural thinking which had produced it. It was an early lesson to me of how if we mistreat the land out of which we come and are fed, we also destroy ourselves. How then are we to live, without seeking the forgiveness of the land itself, and renewing creation together?...  Years ago in the east end of London, I met a remarkable little old lady. She was what some call a ‘bag lady’: a homeless woman who carries her possessions with her, perhaps in just a pair of plastic bags. Her story was typical of many homeless people, although very unique, like that of every homeless person. In this lady’s case, she would tell a very brief biographical tale on a kind of continuous loop. This began with the words ‘I was a Barnados girl’, which, when repeated would start her off again on her abbreviated life-story. Was she then a sad person lost in a tiny, poor and vulnerable world, cut off from the rest of us? No, not exactly. For, in some ways, she was more in touch with existence than most, if not all of us. For this seemingly poor and aged waif had an amazing quality: namely the ability to see the plants and the animals alive around her, even in the middle of such a busy and environmentally threatening city as London then was. If you walked along with her for just a minute or two, she would point out, and open your eyes and ears to, the animal and plant life you almost always missed: the grass and the sometimes beautiful flowers which pushed through the concrete and the cracks; the birds and the insects and the urban wildlife, which, sometimes incomprehensibly, managed to thrive in the otherwise all-too-human jungle of the city. Almost everyone else was too busy, or too self-obsessed, to ‘consider’ these ‘lilies of the field’ and ‘birds of the air’. It took a similarly overlooked human being to notice and to celebrate these astonishing signs of God’s resistance. And, as she drew you into such contemplation and celebration, you thereby discovered the presence of mystery and grace. Are homilies necessary in Holy Week? I wonder. Even more than at other times, our liturgical patterns are shaped so much by the Passion narrative as a whole that interrupting it with other words can seem somewhat intrusive. For the main thing is to enter into the narrative and drama of the Holy Week and Easter mysteries. We do not have to understand everything, or even say or do anything. We are simply invited into the narrative to become part of it and to allow the drama to form the core of our lives. For our task in the whole of our Christian lives is to become more like Christ, in Christ’s life, death and resurrection: to be Christ-formed, cross-formed, resurrection-formed. So it is not a doctrine of the cross we seek to know today. It is its claim and shape in our own lives. Maybe however, just a few words can help us on that journey?...

Making a transition is rarely easy, is it? Currently I’m conscious of many changes in which I am involved, some of which will take much time, wisdom and energy to unfold. We are, of course, in the very midst of such a change this morning, as Penny and I lay down our callings here, and as all of us open ourselves to the new things that God will do with us in the future. As such, this is a special, and precious, moment, as all holy transitions are. For the test, and the fruit, of God’s love is often found where we experience change. After all, as we see again, strikingly, in our Gospel reading today, our God is a God of a new creation, always calling us forth into new life and growth. Like John the Baptist, some of us are called to let go and pass on the baton. Like the disciples we are all called to ‘come and see’ where Jesus is calling us. Like Simon, we may be called to new names and purposes. Don’t you agree Penny?... |

Authors

sermons and reflections from Penny Jones & Josephine Inkpin, a same gender married Anglican clergy couple serving with the Uniting Church in Sydney Archives

June 2024

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed