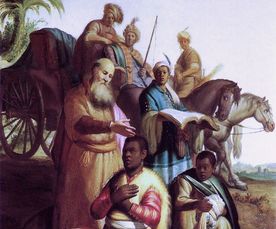

‘Do you understand what you are reading?’ Philip’s question in Acts of the Apostles chapter 8 is such a great one, and it echoes down the centuries. Do we understand what we are reading when we read scripture? Whether we are conservative or varying degrees of liberal, it is easy to think we do. But do we really? This question is one reason that we have a sermon, or homily, or, as this community likes to call it, a reflection, in worship. For, as the eunuch responds, how can we understand unless we have a guide? The alternative is just using scripture as a looking glass, reflecting only our own faces, hopes, fears, and presuppositions. Note well, a guide to scripture is not a simple giver of answers, and certainly not determinative for all times and places. For we continue to reflect on scripture, again and again, precisely because God’s living Word, capital ‘W’, is revealed in scripture but is not fixed within its small ‘w’ words. Rather, as the great biblical interpreters have always said, God’s living Word emerges out of scripture in the encounter of human beings with the text, as guided by one another, our contexts and our deep Tradition, through the power of the Holy Spirit, the ultimate guide and inspirator. This is crucial to recall, lest we are tempted to believe that scripture is too easily understood: whether over-exalted into an idol or a supposed instruction manual, as conservatives are sometimes drawn to do; or reduced to a mere item of intellectual curiosity or piece of cultural heritage, as progressives are inclined to do. Either way, that loses the real subversive power of faith which scripture can hold for us, particularly in stories such as of the Ethiopian eunuch: which, in my view, is one of the most subversive of all in scripture, not least in its queering dimensions…

0 Comments

Over the past few years at this service we have tried to focus on those who are presumed to have been present at the last supper of Jesus, but who are invisible in the written accounts – especially those who were not male or in any kind of authority. In a city like Sydney, where the presence of women and sexually and gender diverse people in church leadership is questioned in many quarters, it seems important on this night to say, ‘we were there too’. With this is mind, I looked for images of women at the Last Supper and came upon this one by Jamie Beck. I know too little about her, but Google suggests she is an American photographer and author of the 2022 book An American In Provence. She worked in New York for various prestigious fashion houses before moving to France. During COVID with her husband Kevin Burg she created a series called Isolation Creation sharing one photo per day of the lockdown experience, creating something beautiful positive each day. They were sold with proceeds going to the Foundation for Contemporary Arts COVID19 Emergency Grants Fund...  In essence, Christmas is quite a queer thing - don’t you think? I don’t really mean its added oddities, like the 19th century, mainly English, extras, like the carols we sing, and the 20th century, mainly American, extras, like the exaltation of Santa. Those are aspects of Christmas down under which are part of our eclectic multiculturalism, even if they partly reflect our settler colonial culture and tend to work better in the northern hemisphere. For we have more than a little work still to do in listening to the Spirit in these lands now called Australia, including turning many of Christmas traditional symbols upside down and inside out. But that is less of a challenge when we truly celebrate the queerness of Christmas, especially in its original, biblically recorded, forms. For the stories of Christ’s birth - God made flesh - are, like queerness, full of extraordinary features, and very difficult to pin down. Indeed, the very idea that God is made flesh was, and is, a horror to many people. That means that matter matters, and, not least, our bodies matter – and every little bit of them – and caring for one another and our planet matters, because ‘matter matters’ and everything shares in this divine matter. Meanwhile, the idea that God is born in, and with, marginal and outcast bodies still seems so absurd and objectionable to many. For the biblical stories and symbols present God’s queer love: the ultimately irresistible power of Love which overturns all the neat boxes and boundaries of our oppressive world, and its typical ways of thinking. So, rather than trying to straighten out Christmas, as many people try to do every year, I believe that we are far better simply to enjoy its very queer ride: which involves keep adding to the oddities of this time of year, with fresh joy and creativity; and letting its divine queerness shine in us…  Plautilla Nelli - The Last Supper (c 1550) Plautilla Nelli - The Last Supper (c 1550) In many ways I hope that when you picked up your liturgy sheet tonight and saw the Renaissance picture of the Last Supper you saw nothing unusual. It’s Maundy Thursday – of course we’ll have a picture of the Last Supper. Some of the art historians among you however will I think have recognised that this is no ordinary painting. This is in fact – as far as we know - the first Last Supper by a female artist – Plautilla Nelli, a contemporary of Michelangelo, Titian and Tintoretto and influenced of course by Leonardo da Vinci who died some five years before her birth in Florence...  One of the most memorable voices of my English schooldays was that of the great cricket commentator John Arlott. He reported on many things, and was also a poet, wine-connoisseur, hymn-writer, part time politician, anti-apartheid spokesperson and renowned host of dinner parties. His distinctive radio tones and brilliant turns of phrase illuminated English summers and some other special occasions, notably the great Centenary Test Match in Melbourne in 1977. Thousands of miles away I remember being curled up through the night listening under the covers to John’s words. His descriptions were typically unforgettable: such as that of the scene of Dennis Lillee’s destruction of the English first innings, where, he said, even the ‘seagulls were standing in line like vultures’, and also Derek Randall’s heroic second innings fightback – an innings as inimitable as John’s own expressions. Gordon Greenidge, the great West Indian batsman, even named him ‘the Shakespeare of commentators.’ Above all, however, I will always cherish John Arlott’s vigorous standing up for our common humanity, not least over apartheid. He had learned to move on from his English colonial upbringing from Indian cricketers, not least the wonderful Vijay Merchant. Famously then, he was involved at the forefront of cricket’s anti-apartheid struggles. Indeed, as early as 1948, visiting South Africa, he refused to fill in the section marked ‘race’ on the departure form, except to put the word ‘human’. ‘What do you mean?’, said an angry immigration officer aggressively. ‘I am a member of the human race’ came back the reply. Eventually he was just told to ‘get out’. How I wonder would John Arlott fare today with resurgent racism, nationalism, and the exclusivism of so many immigration policies? What price human unity today? What, in this Week of Prayer for Christian Unity, does faith have to contribute?...  As each of us comes to worship today, how are we going in our lives and faith? Are we ourselves wrestling with challenging things in our lives, and with God? Are we bearing wounds? Are we seeking blessing, or feeling blessed? In what ways are we perhaps ‘God’s Wrestlers’, ‘God’s Wounded’, ‘God’s Blessed’? These are but three different ways of approaching the great Hebrew story we encounter today in our lectionary (Genesis 32.22-31) - the story we may call Jacob’s Wrestling with the Angel, or alternatively, Jacob’s Wounding, or Jacob’s Blessing...  Taking up today’s Gospel (Luke 15.1-10), I want to speak about three things: queer sheep, the value of women’s coins, and rainbow repentance; about how queer sheep need revaluing; about how women’s coins challenge Church and world to rainbow repentance; and about how rainbow repentance involves renewing pride in queer sheep. Firstly though, let me speak of a cartoon highlighting these themes. For, like a good picture, an insightful cartoon can paint a thousand words…  Amidst the storm and heat, is there anything else to say about marriage from a Christian point of view? Well, yes, as larger dimensions are often ignored in marriage debates, not least among we Christians who claim to ‘know’ what the scriptures ‘teach’. So much has been couched in terms of modern individualistic bourgeois values that one wonders how many people have actually read, and pondered, either the history of marriage, or the scriptures that make some people, on different sides of the arguments, so jumpy. Actually, the official Australian Marriage Equality body did not really help during that awful postal survey. Whilst its aims were (for me at least) manifestly just, the mainstream campaign was not only reluctant to engage with controversy directed against gender diverse persons, but it was frustratingly often built on limited ideas of marriage as the choice merely of two individual persons, reflecting conventional contemporary norms of ‘couple-dom’. Now, admittedly, this was in the context of civil marriage alone. Yet, in this, in its assumptions about marriage, it was not so different from narrow ideas certain Christians seem to have. Instead, when we look at the Bible and Christian Tradition as a whole, we find something much, much, bigger. Today’s reading from Isaiah chapter 62 is a powerful expression of this. For, in Isaiah, as elsewhere in the Bible, marriage is not so much about an individual’s bourgeois expression of identity and legal and moral relationship to another individual. Nor is it ultimately really much about sex or gender, though those human aspects are caught up in biblical conceptions in a series of different ways. Rather, marriage is a profound symbol of divine relationship, involving the transformation of everything. For, as Isaiah 62 verses 1-5 makes startlingly clear, biblical marriage is about the marrying of all things, bringing healing and the restoration of justice and peace. Indeed, marriage as a vehicle of transformation is not only about whole communities rather than individual persons alone, but it is also not simply about human beings alone. It is also about the marrying of land, and creation as a whole: the fullness of the ‘new creation’ prophesied in Isaiah and fulfilled in Christ. Our little human relationships, if hugely precious, are ultimately just elements in this. For it it is thus so much more radical than any conventional conception of marriage…  Storms about sex and gender increasingly rage around, and, importantly, within us. In the face of this, what stories are we telling ourselves, and living into? How are we negotiating the tempests of faith, fact and false news? Where are we headed and what hope do we have? Let us take time to consider. For the sea of faith of which we are a part is in much turmoil because of sex and gender waves. It is likely to remain so, and even grow more turbulent. What options are among us then, and, most vitally of all, where is God in all of this?  If the 3 ‘Rs’ have been said to be the foundation of learning, then there is a case for saying that the writer of Acts of the Apostles gives us 3 ‘Ps’ as the foundation of Christian identity and mission. For in Acts chapter 8 we read today’s passage about Philip and the eunuch. This is immediately followed, in chapter 9, by the story of Paul’s conversion and acceptance into the Christian community. Then, in chapter 10, we have the story of Peter’s strange dream which leads to his conversion to the full acceptance of Gentiles without demands. Typically these stories are treated separately, as discrete events in the life of the early Church. Yet I wonder. May they not actually be interconnected, as part of one truly remarkable story told by Acts? For in these stories we see something of how the early Jewish Christian sect became a highly engaged and outward looking community of radical inclusion: embracing the outcast, the oppressed and the oppressor, from whatever race, religion or other identity they came. This was a truly extraordinary shift in attitude and practice. Of course the seeds were very much present in the Hebrew scriptures and, above all, in the praxis of Jesus. Yet it still represents perhaps the greatest conversion in all Christian history: beyond, for example, the Church’s turn around on slavery or on the full acceptance and ministerial empowerment of women. No wonder therefore that the writer of Acts gives us three powerful stories to help us grasp the point. Sadly we sometimes divide them off from one another and tend to lose this dynamic. Peter and, especially, Paul’s stories then lose some of their context and bite. In the case of today’s story, of Philip and the eunuch, we can overlook it altogether. To do so may be to miss vital lessons for our mission and Christian self-identity today... |

Authors

sermons and reflections from Penny Jones & Josephine Inkpin, a same gender married Anglican clergy couple serving with the Uniting Church in Sydney Archives

June 2024

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed