‘Do you understand what you are reading?’ Philip’s question in Acts of the Apostles chapter 8 is such a great one, and it echoes down the centuries. Do we understand what we are reading when we read scripture? Whether we are conservative or varying degrees of liberal, it is easy to think we do. But do we really? This question is one reason that we have a sermon, or homily, or, as this community likes to call it, a reflection, in worship. For, as the eunuch responds, how can we understand unless we have a guide? The alternative is just using scripture as a looking glass, reflecting only our own faces, hopes, fears, and presuppositions. Note well, a guide to scripture is not a simple giver of answers, and certainly not determinative for all times and places. For we continue to reflect on scripture, again and again, precisely because God’s living Word, capital ‘W’, is revealed in scripture but is not fixed within its small ‘w’ words. Rather, as the great biblical interpreters have always said, God’s living Word emerges out of scripture in the encounter of human beings with the text, as guided by one another, our contexts and our deep Tradition, through the power of the Holy Spirit, the ultimate guide and inspirator. This is crucial to recall, lest we are tempted to believe that scripture is too easily understood: whether over-exalted into an idol or a supposed instruction manual, as conservatives are sometimes drawn to do; or reduced to a mere item of intellectual curiosity or piece of cultural heritage, as progressives are inclined to do. Either way, that loses the real subversive power of faith which scripture can hold for us, particularly in stories such as of the Ethiopian eunuch: which, in my view, is one of the most subversive of all in scripture, not least in its queering dimensions…

0 Comments

image: Kamala Bright on Unsplash image: Kamala Bright on Unsplash ‘Tell me the old, old story, when you have cause to fear.’ Yes? No? Maybe? How do you respond to that: and, more broadly, to faith, and God, in Jesus, as story? Many years ago, on the radio, one of the radical thinking clergy of the Church of England was asked about how they understood God. ‘God’, they said, ‘is the poem in which I live my life.’ Yes? No? Maybe? Does that resonate with you? Many people, secular and faith-based, would be quite dismissive. Stories, and poems not least, they would say, are typically fanciful and not factual, fabricated and too often false. Of course, that kind of response generally lacks self-awareness and is very narrow, and, often, quite ideological. Apart from not recognising that different expressions of life have their own characteristics and validity, they typically miss the way in which story, metaphor, and symbol, exist within all areas of knowledge. Science for example is full of different models, and ideas like evolution are themselves stories. Scientists are right in saying that life-giving stories are helped by empirical verification. Yet, without stories as such, it is impossible for human life and consciousness to exist. That is something that liberals and progressives, especially in faith spaces, have often missed. It is not enough to point out the weaknesses in a tired traditionalist story: whether that be about creation, sexuality, or anything else. Even more importantly, we also need to tell a new story. Populist politicians, like rabble-rousing religious preachers, know this well. Facts are malleable but stories, once established, persist: whether they are particular ways of understanding the body, the nation, the world, and, of course, God. All of us therefore have stories, conscious and unconscious, running through our heads: some of them planted there long ago, some of them picked up from the latest social media frenzy; some of them giving life-giving purpose to our lives, others providing scripts that limit us but which are hard to shake off. What then is our story?...  image by Josh Eckstein on Unsplash image by Josh Eckstein on Unsplash Some of you may have noticed a change to our worship space today. The baby has gone – transformed it seems into a scallop shell. I am passing it around among you as I speak and I invite you to hold it for a few moments if you wish... ...Now, what strange alchemy is this, you may ask? What does this signify? We’ll come back to that. For now, just be aware that we are being subtly, and not so subtly, redirected, from the outer to the inner; from the seen to the unseen; from creation to re-creation; from the incarnation to the resurrection. This is a theological progression that demands that we go back to the beginning – to the creation of light in the story of Genesis as we heard, and to the beginning of the gospel as the author of Mark proclaims it just a couple of verses earlier than today’s text, ‘the beginning of the good news of Jesus Christ, the Son of God’...  One of the great things about theology from the margins is how it brings the Bible alive in liberating ways. Therefore, as the young gay Sydney Anglican Joel Hollier puts it, for many queer folk like he and I, ‘we’re not queer despite the Bible. We’re queer because of the Bible.’ As we read the Bible ‘with queer eyes’, more and more sexually and gender diverse people are renewing the very elements which gave the Bible power in the first place: seeing and exploring the extraordinary diversity and dynamic of goodness in creation and human bodies; the central call to justice and infinite compassion for all; the redeeming power of love in the face of suffering and death; and the resurrection promise of new life and flourishing found in the transforming work of the Holy Spirit in the world. That is one reason why, personally, I’m so over the old arguments about sexuality and gender, not least the so-called ‘clobber texts’. Honestly, why on earth would we waste time on others’ hang-ups, when we’ve such good news to explore and share? In this, today’s reading from the Acts of the Apostles (Acts 9.36ff) is a striking example. For in Tabitha/Dorcas, we find a startling model of discipleship from the margins: truly, an evocative, entrepreneurial, exemplar…  Over the last few weeks I have had the wonderful, if challenging, experience of sharing in leading the God, Humanity and Difference course at St Francis’ College. This has included looking at a wide range of human differences: including those of race, disability, gender, sexuality, faith, culture, history, and socio-economic position. We have heard from a variety of voices from across our Church and world: including Canon Bruce Boase (as an Aboriginal priest, as we explored Reconciliation issues) and, not least, Elizabeth and Ann from our very own congregation here (as we explored faith issues related to disability). In addition, we have been blessed by the insights of the rich mix of backgrounds and experiences within the class itself, including students originally from Sudan and Korea. Sometimes this has meant that we have met fresh questions and ideas which will require some working out. For our God-given human differences are not always easy for us all to live with. We can see that clearly in some of the conflicts and controversies of our Church and world today. Yet, as we have discovered in our course this semester, if we hold them prayerfully, and work with them with intelligence and compassion, they are powerful gifts to us for healing, new life, and flourishing together. For properly to hear each of us, speaking our own witness to God in our own way, is to let the Holy Spirit fly free in fresh experiences of Pentecost… When are where did you receive a ‘call’ to a new ministry in the Church? Did it come gradually upon you, or was there a particular turning point? For what it is worth, in my case it has probably happened over a period of time. However I do remember getting on a train in rural Lincolnshire to travel to Birmingham to stay with some friends. Such a cross-country journey can often be a little grueling, for UK train lines which do not involve London are typically less speedy and more complicated. So it was that five hours of stop and starts provided me with plenty of time for reflection, at the end of which a new sense of vocation had been planted in me. If Margaret Thatcher had no time for the old nationally owned British Rail, God clearly did! In what way though, if any, do our own calls to ministry compare with those of the disciples in today’s Gospel (Luke 5.1-11)?...

Shall we agree to disagree? No, we won’t. That has been the answer to that question through much of human history, hasn’t it? Isn’t it still the answer today in many places and in many parts of our own lives, including within the Anglican Communion today? As human beings we really struggle with the idea of unity on any other basis than what seems good, and restricted, to us. We see this played out, time and time again, in politics, in the great events of the world, in contested issues within the church and other community groups, and in our own family and personal lives. So praying for Unity and Reconciliation, as we do today, is a real challenge. For what kind of unity and reconciliation are we actually praying? Is it that our will, or God’s will, be done? Is a different answer to the question ‘shall we agree to disagree?’ part of this? I have been reflecting on these things over the last few days in relation to three key issues which have touched my heart: namely the terrorist bombing in Manchester, the campaign for Marriage Equality (a keynote Brisbane meeting of which I attended this week), and Australian Reconciliation. Each raise thorny problems if we look at them in certain ways. Yet they offer us encouragement to true unity with genuine diversity if we regard them in other ways. For how do we picture unity? It makes all the difference how we see it… One of the most memorable, transforming, and ultimately deeply poignant sermons I ever heard was at theological college, over thirty years ago, when I was what we now call a formation student. The address was given by an American student who was with us for a short while. It was on the subject of Peter’s dream in the Acts of the Apostles and the remarkable turnaround in the early Church which we hear about in Acts chapter 15 today. Far from being remote events, my fellow student brought them alive in an intensely powerful way. This, you may understand, was during the last tumultuous days of controversy before the ordination of women in the Church of England and in the first real stirrings of pain and freedom among LGBTIQ+ people across the world. Yet, challenging though those things were, and still are some even today, they are nothing, my fellow student pointed out, to the radical transformation we find in these texts from Acts. For centuries, almost forever really, we, the Gentiles, with our characteristics and our lifestyles, lay outside full inclusion in the body of God’s community. Yet Paul, Peter, and even James, the bulwark of Jewish Christian foundations, came to welcome us as equals in the life of salvation. In contrast, how much lesser such a conversion is asked of us, said my fellow student. So can we, as Peter, as Church, embrace today those who also who, like the Gentiles long ago, not only come to us, but even flourish among us, against the odds, against our human-fashioned, provisional rules?...

A few weeks ago I asked a local rabbi what was the Jewish ‘take’ on Saul of Tarsus, otherwise known to Christian as St Paul. The rabbi said that there really wasn’t a view. Now he may not have quite understood what I was asking, or perhaps he was simply trying to be diplomatic and avoid controversy. For surely, over the centuries, Jews have had something to say about Paul, particularly when he has been regarded, in some Christian quarters, as an archetypal model of Jewish conversion. The rabbi’s response however was also suitably chastening. Christians may rightly hold Paul in high regard, even some awe. Why though would Jews have much consideration for him? He left the faith and, in doing so, no longer belonged to Jewish history. Judaism essentially simply moved on. Christians must therefore be careful not to read into our understanding of Jewish-Christian relationships particular aspects of St Paul which are precious to us. This is certainly something to be borne in mind when we hear biblical passages like this one from Acts chapter 13 today. Jewish-Christian relationships have always been much more complex than many people have often wanted them to be, and this is clear from the history of the first Christian centuries…

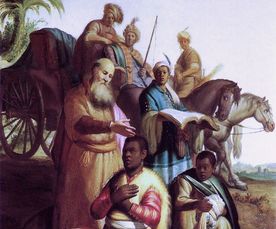

If the 3 ‘Rs’ have been said to be the foundation of learning, then there is a case for saying that the writer of Acts of the Apostles gives us 3 ‘Ps’ as the foundation of Christian identity and mission. For in Acts chapter 8 we read today’s passage about Philip and the eunuch. This is immediately followed, in chapter 9, by the story of Paul’s conversion and acceptance into the Christian community. Then, in chapter 10, we have the story of Peter’s strange dream which leads to his conversion to the full acceptance of Gentiles without demands. Typically these stories are treated separately, as discrete events in the life of the early Church. Yet I wonder. May they not actually be interconnected, as part of one truly remarkable story told by Acts? For in these stories we see something of how the early Jewish Christian sect became a highly engaged and outward looking community of radical inclusion: embracing the outcast, the oppressed and the oppressor, from whatever race, religion or other identity they came. This was a truly extraordinary shift in attitude and practice. Of course the seeds were very much present in the Hebrew scriptures and, above all, in the praxis of Jesus. Yet it still represents perhaps the greatest conversion in all Christian history: beyond, for example, the Church’s turn around on slavery or on the full acceptance and ministerial empowerment of women. No wonder therefore that the writer of Acts gives us three powerful stories to help us grasp the point. Sadly we sometimes divide them off from one another and tend to lose this dynamic. Peter and, especially, Paul’s stories then lose some of their context and bite. In the case of today’s story, of Philip and the eunuch, we can overlook it altogether. To do so may be to miss vital lessons for our mission and Christian self-identity today... |

Authors

sermons and reflections from Penny Jones & Josephine Inkpin, a same gender married Anglican clergy couple serving with the Uniting Church in Sydney Archives

June 2024

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed