image: Kamala Bright on Unsplash

image: Kamala Bright on Unsplash

image: Kamala Bright on Unsplash image: Kamala Bright on Unsplash ‘Tell me the old, old story, when you have cause to fear.’ Yes? No? Maybe? How do you respond to that: and, more broadly, to faith, and God, in Jesus, as story? Many years ago, on the radio, one of the radical thinking clergy of the Church of England was asked about how they understood God. ‘God’, they said, ‘is the poem in which I live my life.’ Yes? No? Maybe? Does that resonate with you? Many people, secular and faith-based, would be quite dismissive. Stories, and poems not least, they would say, are typically fanciful and not factual, fabricated and too often false. Of course, that kind of response generally lacks self-awareness and is very narrow, and, often, quite ideological. Apart from not recognising that different expressions of life have their own characteristics and validity, they typically miss the way in which story, metaphor, and symbol, exist within all areas of knowledge. Science for example is full of different models, and ideas like evolution are themselves stories. Scientists are right in saying that life-giving stories are helped by empirical verification. Yet, without stories as such, it is impossible for human life and consciousness to exist. That is something that liberals and progressives, especially in faith spaces, have often missed. It is not enough to point out the weaknesses in a tired traditionalist story: whether that be about creation, sexuality, or anything else. Even more importantly, we also need to tell a new story. Populist politicians, like rabble-rousing religious preachers, know this well. Facts are malleable but stories, once established, persist: whether they are particular ways of understanding the body, the nation, the world, and, of course, God. All of us therefore have stories, conscious and unconscious, running through our heads: some of them planted there long ago, some of them picked up from the latest social media frenzy; some of them giving life-giving purpose to our lives, others providing scripts that limit us but which are hard to shake off. What then is our story?...

0 Comments

Maybe what she wanted to do was punch Him (God) But she couldn’t So Sarah laughed Didn't Suzanne Terry put it well in her poem 'Sarah Laughed'? How many of us have wanted to punch God, or worse, for what has happened, or not happened, to ourselves and others? In Genesis chapter 18, Sarah laughs out of her deep experiences of sorrow, anger, and utter frustration, with God. After all she has experienced, as a childless migrant woman, in an ancient patriarchal culture where child-bearing was so important, how dare God turn up and now declare fresh hope. Why take so long to give this gift? Why put Sarah through such trials? We can easily identify. As elsewhere in the Bible, we are not presented with a simple moral or spiritual inspiration. Rather we encounter a very human struggle, with which we are invited to wrestle. Suzanne Terry’s poem is a product of this. For she was responding to a book entitled Those Who Wait: Finding God in Disappointment, Doubt and Delay. This, like other writings by Tanya Marlow, seeks to explore how we live with the realities of suffering…  photo: by Ashin K Surash on Unsplash photo: by Ashin K Surash on Unsplash Today’s reading from Luke begins with the often-repeated phrase ‘don’t be afraid’. It is a phrase so often repeated that it has given me pause for thought this week. Do the Scriptures encourage us all the time not to be afraid, precisely because the people for whom they were written were in fact constantly afraid? They would have had good reason to be. As far as we can tell most early followers of Jesus were subject peoples living in occupied territory. The might of Rome was a constant threat, taxes were high, financial insecurity inevitable, and it was not as though they had the securities of modern medicine, analgesics, and antibiotics. Moreover, the expectation of Christ’s imminent return, coupled with an increasing impatience at its delay sounds an anxious apocalyptic note throughout the pages of the New Testament. But what about ourselves? Are we also afraid? Religion has after all for centuries traded in fear – fear of God’s punishment and condemnation, sweetened by the promise of salvation for those who truly believe, (some have called that ‘pie in the sky when you die’); treasures in heaven beyond the reach of moth, rust, and thieves – and after the last few months in Sydney I’d want to add mould! So, are we also afraid? This is an important question as we enter a period of considering our mission as a congregation. If we are afraid, what are we afraid of? – remembering that fear is not all bad. It is a great motivator to action. But the encouragement of the gospel is not to be afraid, but to act from a different place – a place where we don’t have supposed ‘treasures’ to defend; a place where we are set free from the need to control and secure; a place indeed as the letter to the Hebrews calls it, of faith...  I can trace my beginnings to a river. For once upon a time in England, in the difficult days of the depression just before World War Two, two men and a woman boarded a ferry across the Mersey – yes, just like the song! One of the men recognised the woman and introduced him to his friend, the other man. Every day as the three of them made their commute by ferry they would meet, and the woman and the second man grew closer. The second man went to war, but in 1942 he came home on leave and they were married. Then, or perhaps it was a different time of leave, the two of them went to the cinema, but the bombs fell as so often at that time. They sheltered under the great Liverpool St George’s Hall in the air raid shelter. But fearful of missing the last ferry across that river, they took a chance and raced to the shelter near the ferry terminal. That was the night the St George’s air raid shelter took a direct hit and all who had sheltered there were killed. Their need to catch the ferry saved the woman and the second man. In 1944 the woman gave birth to a baby – that child is my older sister. The river, and the ferry that crossed it brought my parents together, and without it, I would not be... Fear and faith, chaos and calm – these are the poles around which this powerful story revolves. No wonder that this story is told in all three of the synoptic gospels. For these are things that we all recognise in our own lives and the lives of others. This is not just a miracle story from long ago. This is our story, both as individuals and as communities. The fear and the faith, the chaos and the calm, they all play out in our daily lives. This is a story that has real, physical actual details. It is also a story whose motifs resonate at the level of dream energy and the deep unconscious...

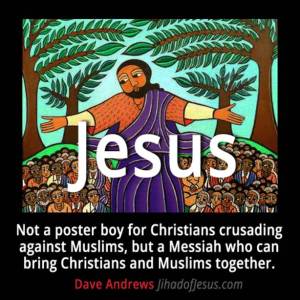

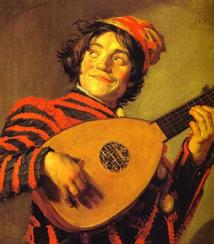

I want to talk about being locked shut and about being breathed open. And I want to explore what it might mean, as Jackie will do today (as she comes to baptism as an adult), to begin again. ‘The doors of the house where the disciples met were locked for fear of the Jews’. Those early disciples were a pretty terrified bunch. Even as the possibility that Jesus could be alive was dawning on them, they remained uncertain, afraid of being arrested and killed. It seems to me likely that they met secretly for a long time. The texts of the New Testament compress what was probably a lengthy process, into the shorter units of symbolic time. But whether these things happened over a few hours and days, or many years hardly matters. What matters is that a change occurred and a new beginning became possible...  What is your favourite Easter story I wonder? I read a lovely one the other day. A teacher had asked her young pupils to write a line or two about what they were going to do over Easter. The children started scribbling away until one little boy put his hand up. ‘How do you spell gun?’, he asked. A little bemused, the teacher replied, ‘G-U-N’. The boy started writing and then put his hand up again. ‘And how’, he said, do you spell die?’ A good deal more perturbed, the teacher replied, ‘D-I-E’, and then she added cautiously, ‘what is it you are going to do?’ ‘Oh’ said the little boy, ‘it is going to be fun… we’re gun die eggs’. Well, a number of folk among us have certainly dyed eggs for today: just one of the many wonderful symbolic traditions which have grown up over the centuries around Easter. Indeed, some of these are perhaps as curious as the little boy’s spelling and grasp of language. They are certainly diverse, rather like the variety of ways in which the Gospel writers and St Paul speak about the Resurrection. Does that matter, do you think? My sense is that that is precisely as it should be. For the Resurrection of Jesus Christ is like an explosion, the impact and implications of which can never be understood and lived out by one tidy account or explanation. Rather the meaning of Easter is only something we grow into, day by day, year by year, as we reflect upon the different ways our Bible and Tradition speak of it, and, crucially, as it comes alive for us in our own lives and times…  What do you think of when you hear the word ‘jihad’ I wonder? For many people the word ‘jihad’ conjures up images of conflagration, disturbance and violence, doesn’t it? Across the world today, there is certainly a very small minority of Muslims who not only think in that way but who actively seek to inflict such images on others and use them to oppress and destroy. The consequence is appalling violence in many places. Of course, that is a hideous betrayal of what mainstream Islam has always understood ‘jihad’ to be. Yes, it has meant active struggle, even active violent struggle, if absolutely necessary, for truth and justice. Yet above all, it means ‘struggling, striving, applying oneself, persevering’ in the way of God. This may mean active, outer, physical struggle (usually nonviolently), but the ‘greater jihad’, as it is has been termed, is the inner, spiritual, struggle of human beings to live in relationship with God. In which case, this, to some degree, is not so far from Christian ideas of what we call ‘discipleship’ or ‘the way of Jesus’. For ‘discipleship’, or ‘the way of following Jesus’ is also a way of struggle: an inner, spiritual, struggle to grow in relationship to God, and an outer, active, struggle to help realise God’s truth and justice in the world. If we see that, then we may be able to understand the challenging words of Jesus in today’s Gospel as a call not to destructive conflict, but to a ‘jihad’, or sacred struggle, for compassion and ultimate healing of our broken lives and world…  Once upon a time, the story goes, there was a court jester. For many years he was very popular with the king. The jester made him laugh and brought joy and well-being to everyone he met. That country was indeed a kingdom of joy and well-being. Then things started to go wrong in the kingdom. The king’s chief advisers, the politicians, became greedy and unjust and the people grew fearful and violent. Their humour they had became dark and cruel. The jester’s wit was no longer appreciated, especially when he spoke in ways which seemed to give comfort to the poor and marginalised. A campaign grew among the powerful to get rid of him. So the king, though he still remembered liking the jester very much, agreed to condemn him to death. To honour his past regard however, the king said that the jester could choose how he was to die. ‘For example, I could have you hung, drawn and quartered’, the king said, ‘or thrown to hungry wolves, or boiled alive, or shot at dawn by a firing squad, or, like the aristocracy, you might have your head chopped off with a silver sword. It is your choice: there are many ways. How would you like to die? You choose and I will decree it.’ So the jester thought for a brief moment and then answered, as quick as a flash: ‘ in that case, my Lord, I would choose to die..’ He paused… ‘by old age.’ And the king roared with laughter and gave the jester his wish. Now what, you may say, has that to do with our Gospel reading this morning? Well, just this: in a sense, that jester embodied three key aspects of Jesus’ teaching - firstly, by not fearing; secondly. by not clinging to possessions or position; and thirdly, by above all remaining awake to the presence of God’s kingdom, whatever happens at any moment. For this is the gift of Jesus, the greatest spiritual Jester of our lives: the One who shares the divine laughter and the invitation to share in the true kingdom of God’s love...  How do we respond to death? I don’t ask that as a negative question but because it is at the heart of our Gospel – our Good News – today, and throughout this Holy Week. It is an unavoidable question, however much we try to avoid it: for, as the old proverb has it, two things are certain in life: death and taxes. Yet, more meaningfully, Christians believe, how we respond to death is at the heart of how we find life in this world, which is the ultimate meaning of our Gospel and the culmination of this Holy Week in the Resurrection. So, as we hear today’s Gospel reading (the story of Christ’s Passion according to Luke) - in three parts - let us reflect upon the challenge of death, so that we may find life again more fully, as Jesus offers it to us… |

Authors

sermons and reflections from Penny Jones & Josephine Inkpin, a same gender married Anglican clergy couple serving with the Uniting Church in Sydney Archives

June 2024

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed