Giovanni di Paolo, “St. John the Baptist in Prison Visited by Two Disciples,” ca. 1455-1460 (photo: Public Domain) Giovanni di Paolo, “St. John the Baptist in Prison Visited by Two Disciples,” ca. 1455-1460 (photo: Public Domain) Try as I might, I have always found John the Baptist to be an off-putting, and certainly a disturbing, figure in the Christian story. And I have tried. For I was ordained deacon in St John at Hackney, a church named after John the Baptist, and I served in the community there. Each year, we would have our patronal festival, and try to find ways to see how the Baptist could relate to our usual church life. To be honest, it was easier than in the past. For St John at Hackney was originally a very high society church – indeed, the focal borough church in Hackney - and its impressive churchyard still contains many notable figures, such as the Baden Powell family, from whom the worldwide scouting movement issued. By the 1980s however, Hackney was both London’s poorest and most multicultural borough, and our congregation was very different; all part of the Anglican Church’s journey in the inner cities from being the church of ‘the great and the good’ to being one of the ‘marginal and the odd’. Over half of our congregation also drew their origins from West Africa or the West Indies. Well, maybe John the Baptist might have felt somewhat at home, being on the prophetic margins of his society. Yet his appearance and demeanour would still have marked him out. Indeed, even some of the more radical and vibrant of our congregation would have struggled with some of his language of repentance and its tone. Similarly, I suspect that we would not be wholly comfortable with him here. For John the Baptist was most certainly a ‘disturber of the peace’ in very uncomfortable ways. Indeed, the story of his violent death we heard this morning is hardly the most attractive within the Bible. So what do we make of it, and of the Baptist’s significance within our faith journey?...  Where, to what, and, perhaps most importantly of all, to whom do you, do we, belong? These are core questions at the heart of faith, and of life itself. Let me therefore begin with a little quiz question, to which those who know 1980s popular music may be able to respond. Who sang the following words? If it helps, think of it sung falsetto by a redheaded young man: You leave in the morning with everything you own in a little black case Alone on a platform, the wind and the rain on a sad and lonely face Mother will never understand why you had to leave But the answers you seek will never be found at home The love that you need will never be found at home The song is Smalltown Boy, sung by Jimmy Somerville, from the British synth-pop band Bronski Beat’s album Age of Consent. It came out in 1984, at the height of Margaret Thatcher’s political power, and, for folk like me – not least small town kids like me – it was emblematic both of protest against oppression and of the creative, joyous, expression of queer courage and change. Indeed, among other things, Bronski Beat also headlined ‘Pits and Perverts’, a concert in London’s Electric Ballroom to raise funds for the Lesbians and Gays support the Miners campaign: an event featured in the film Pride. Smalltown Boy also reached number 8 in the Australian charts and it is but one symbol of the historical struggle which has led, finally this week, to a formal apology from the New South Wales government for the horrendous abuse and violence that has been inflicted on queer people, and not least on gay young men who were told, in no uncertain terms, that they did not belong. Yes, let us celebrate that! Today Smalltown Boy is a celebration of what was largely still a declaration not to be crushed, but to survive, and thrive. For as Jimmy Somerville sang: Pushed around and kicked around, always a lonely boy You were the one that they'd talk about around town as they put you down And as hard as they would try they'd hurt to make you cry But you never cried to them, just to your soul No, you never cried to them, just to your soul Soul power eh? As Jesus, another smalltown kid, taught, and showed, this is ultimately at the heart of any life-giving change. For it is where we find our true belonging…  ‘Do you understand what you are reading?’ Philip’s question in Acts of the Apostles chapter 8 is such a great one, and it echoes down the centuries. Do we understand what we are reading when we read scripture? Whether we are conservative or varying degrees of liberal, it is easy to think we do. But do we really? This question is one reason that we have a sermon, or homily, or, as this community likes to call it, a reflection, in worship. For, as the eunuch responds, how can we understand unless we have a guide? The alternative is just using scripture as a looking glass, reflecting only our own faces, hopes, fears, and presuppositions. Note well, a guide to scripture is not a simple giver of answers, and certainly not determinative for all times and places. For we continue to reflect on scripture, again and again, precisely because God’s living Word, capital ‘W’, is revealed in scripture but is not fixed within its small ‘w’ words. Rather, as the great biblical interpreters have always said, God’s living Word emerges out of scripture in the encounter of human beings with the text, as guided by one another, our contexts and our deep Tradition, through the power of the Holy Spirit, the ultimate guide and inspirator. This is crucial to recall, lest we are tempted to believe that scripture is too easily understood: whether over-exalted into an idol or a supposed instruction manual, as conservatives are sometimes drawn to do; or reduced to a mere item of intellectual curiosity or piece of cultural heritage, as progressives are inclined to do. Either way, that loses the real subversive power of faith which scripture can hold for us, particularly in stories such as of the Ethiopian eunuch: which, in my view, is one of the most subversive of all in scripture, not least in its queering dimensions… Jesus is the good shepherd. Hopefully we all know that. Those of us who went to Sunday school learnt this in the first lesson often accompanied by a picture of a rather anaemic looking Jesus with flowing locks, cuddling a snowy white lamb who had clearly never done a day’s manual labour in their life! Is that right?...

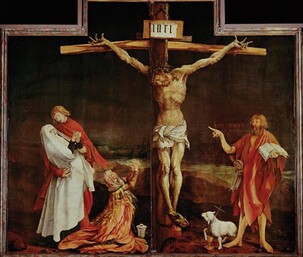

image: Kamala Bright on Unsplash image: Kamala Bright on Unsplash ‘Tell me the old, old story, when you have cause to fear.’ Yes? No? Maybe? How do you respond to that: and, more broadly, to faith, and God, in Jesus, as story? Many years ago, on the radio, one of the radical thinking clergy of the Church of England was asked about how they understood God. ‘God’, they said, ‘is the poem in which I live my life.’ Yes? No? Maybe? Does that resonate with you? Many people, secular and faith-based, would be quite dismissive. Stories, and poems not least, they would say, are typically fanciful and not factual, fabricated and too often false. Of course, that kind of response generally lacks self-awareness and is very narrow, and, often, quite ideological. Apart from not recognising that different expressions of life have their own characteristics and validity, they typically miss the way in which story, metaphor, and symbol, exist within all areas of knowledge. Science for example is full of different models, and ideas like evolution are themselves stories. Scientists are right in saying that life-giving stories are helped by empirical verification. Yet, without stories as such, it is impossible for human life and consciousness to exist. That is something that liberals and progressives, especially in faith spaces, have often missed. It is not enough to point out the weaknesses in a tired traditionalist story: whether that be about creation, sexuality, or anything else. Even more importantly, we also need to tell a new story. Populist politicians, like rabble-rousing religious preachers, know this well. Facts are malleable but stories, once established, persist: whether they are particular ways of understanding the body, the nation, the world, and, of course, God. All of us therefore have stories, conscious and unconscious, running through our heads: some of them planted there long ago, some of them picked up from the latest social media frenzy; some of them giving life-giving purpose to our lives, others providing scripts that limit us but which are hard to shake off. What then is our story?...  image: Brandy Martell, 400 block of 13th St near Frankland St, Oakland image: Brandy Martell, 400 block of 13th St near Frankland St, Oakland ‘Tell all the truth', wrote the poet Emily Dickenson, 'but tell it slant’. For ‘The Truth must dazzle gradually/Or every one be blind.’[1] That is pretty much Mark’s Gospel’s account of resurrection, isn’t it? Whilst other resurrection stories were attached later, the two earliest, and arguably the best, manuscripts of Mark’s Gospel stop abruptly at verse 8 of chapter 16, with women fleeing from an empty tomb and ‘saying nothing to anyone, for they were afraid.’ Furthermore, the text simply stops in mid-sentence, with the little preposition which means ‘for’. Mark’s Gospel, at least, is clear that resurrection is both truly astounding and impossible to convey straightforwardly. For how do we describe resurrection? How do we communicate resurrection? How do we live resurrection? The nature of resurrection is that it involves strange truths of transformation: which require, like so much great art, ‘telling it slant’; which rest on mystery; and which revolve around deep, lived, experience. For art, mystery, and experience: these three things are at the heart of the strange truths of resurrection we exult in today, as witnessed to by our readings and key images this morning, and the continuing life of you and I, and all who follow Christ…  What kind of a crucifixion do we share in on this Good Friday? Is the cross a threat, a judgement, or even a weapon? Is it simply a site and symbol of death and destruction? Or is it a pathway of transformation, for us and for our world? To help us enter it as a pathway of loving transformation, I want to offer a few words around four different images of crucifixion, which may support us in our spiritual journeying today. Each is an image from the suffering of the last century of our modern world. Each, in different ways, represents the crucifixion afresh, and encourages us to know transformation. Let me first however, in introduction, share this great image of the crucifixion from Matthias Grünewald, painted for the Isenheim Altarpiece in the hospital chapel of St Anthony’s monastery. What do you see in it?...  green heart image by Adithya Vinod on Unsplash green heart image by Adithya Vinod on Unsplash Let us think about three things – about greenery, about the Sydney GreenWay, and about Hildegard’s Latin word ‘viriditas’, meaning greenness or verdancy, that informed out recent entry in the Mardi Gras parade. And let’s keep in the back of our minds a couple of questions – what connects Jesus’s entry into Jerusalem with Extinction Rebellion? Ad what might Hildegard and the GreenWay have to say to the vibrancy and future of the church in our own time?...  image: by Suzanne D.Williams on Unsplash image: by Suzanne D.Williams on Unsplash As a pioneer female priest, one of my wife’s achievements was becoming the first female Rector of the parish of Stanhope, sometimes known as ‘the Queen of Weardale’, high up on the roof of England. She added to a line going back to the year 1200, including some famous names in church history. For whilst, financially and in other ways, ministry in remoter rural areas is challenging today, centuries ago Stanhope was known as the richest living in the north of England for clergy. This was because, way back then, the Church of England drew tithes from local people, who, in the Durham Dales, were chiefly miners and poor farmers and agricultural workers. Not for nothing was this then a significant contributor to the Dales, and County Durham as a whole, becoming strongly Methodist. There is a wonderful little story however about one of my wife’s distinguished predecessors, Joseph Butler. Butler not only became Bishop of Bristol and then of Durham, but, alongside helping to develop 18th century economic theory, he is best known as one of the leading theologians of the day: so much so that the Church of England commemorates him each year on 16 June. Now Butler had been head chaplain to King George II’s wife, Caroline. Some while after he had moved to Stanhope, the Queen therefore asked around the royal court. ‘does anyone know what has happened to Butler? Is he dead?’ ‘No, ma’am’, came back the reply by one in the know, ‘he is not dead, only buried’. ‘Not dead, only buried’: what a wonderful phrase, and one resonating both with our Gospel reading (John 12.20-31), and with our reflections on Celtic Christianity this morning… |

Authors

sermons and reflections from Penny Jones & Josephine Inkpin, a same gender married Anglican clergy couple serving with the Uniting Church in Sydney Archives

June 2024

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed