‘Do you understand what you are reading?’ Philip’s question in Acts of the Apostles chapter 8 is such a great one, and it echoes down the centuries. Do we understand what we are reading when we read scripture? Whether we are conservative or varying degrees of liberal, it is easy to think we do. But do we really? This question is one reason that we have a sermon, or homily, or, as this community likes to call it, a reflection, in worship. For, as the eunuch responds, how can we understand unless we have a guide? The alternative is just using scripture as a looking glass, reflecting only our own faces, hopes, fears, and presuppositions. Note well, a guide to scripture is not a simple giver of answers, and certainly not determinative for all times and places. For we continue to reflect on scripture, again and again, precisely because God’s living Word, capital ‘W’, is revealed in scripture but is not fixed within its small ‘w’ words. Rather, as the great biblical interpreters have always said, God’s living Word emerges out of scripture in the encounter of human beings with the text, as guided by one another, our contexts and our deep Tradition, through the power of the Holy Spirit, the ultimate guide and inspirator. This is crucial to recall, lest we are tempted to believe that scripture is too easily understood: whether over-exalted into an idol or a supposed instruction manual, as conservatives are sometimes drawn to do; or reduced to a mere item of intellectual curiosity or piece of cultural heritage, as progressives are inclined to do. Either way, that loses the real subversive power of faith which scripture can hold for us, particularly in stories such as of the Ethiopian eunuch: which, in my view, is one of the most subversive of all in scripture, not least in its queering dimensions…

0 Comments

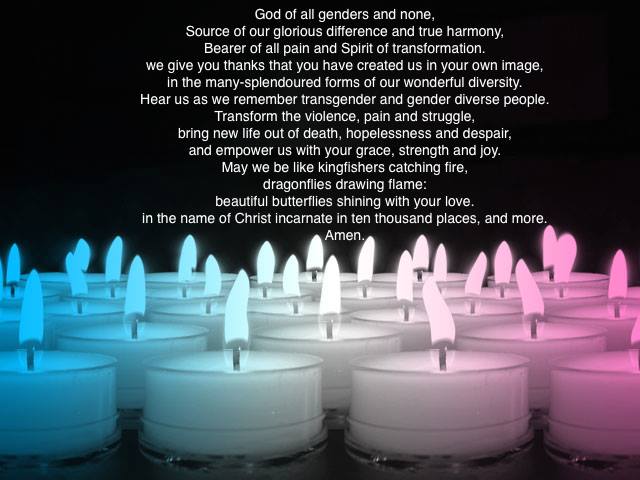

scene from Sense8 scene from Sense8 Ecstasy – what does that word mean to you? Ecstasy certainly has many associations! Some of these are deeply sacred, others far more profane. Each however has something in common: they are about standing out: standing out of the ordinary. For in its Greek origins, ecstasy means exactly that. ‘Ek’ means ‘out of’ and ‘stasis’ means ‘standing: hence ‘ek-statis’ – standing out, or away from, the norm. Ecstasy certainly therefore has important philosophical and theological aspects. Take, for example, the queer Cuban American theorist José Esteban Muñoz. I have been thinking about Muñoz because the theme of this year’s Sydney Mardi Gras is ‘Our Future’ and Muñoz gave a great deal of creative thought to imagining more loving futures. For Muñoz suggested that, in contrast to what he called ‘straight time’, at their/our best, queer people live and invite others into what he called ‘ecstatic time’. In other words, instead of living with the ‘normal’ expectations of time and this world, at their/our best, queer people seek to live and reshape this world differently. Instead of our pasts, our presents, and our futures being shaped by our birth families, and by ‘straight’ drives’ for power, children, inheritance, and wealth, at their/our best, queer people seek different kinds of happiness and societal arrangements. For, like other historically marginalised people, queer people have typically been ‘ecstatic’ people. We/they have stood outside of ordinary life and time: which is very much where our two main figures in our biblical story tonight come in – Naomi and Ruth – as striking models of the ‘ecstatic community’ into which God calls us…  I thought it might be helpful this morning to bring along a favourite bowl of mine. It was made by an artist friend Kerry Holland, whose paintings and bowl sculptures on the theme of The Visitation is currently on exhibition in Pitt Street Uniting Church. She also made this one, which she gave to me as a gift when I came out as transgender, affirming my authentic gender identity a few years ago. It is precious to me for that reason but also because, like all of Kerry’s bowl sculptures it is unique, with its own particular shape, story, and constellation of colours. In that sense, it is like each human being: an exquisitely unique and special divine creation. The more I reflect upon that, and upon the nature of a bowl itself, the more I am also drawn into the love of God. So I would like to share with you some ways in which each of us might helpfully use a bowl as a prayerful way into appreciating ourselves and others and holding together what can easily be misused in the Gospel parable (Matthew 25.31ff) which we heard read just now. For, whilst that passage is in some ways quite straightforward in the challenge it offers us, it is also presents some questions, particularly in the way it divides people into two black and white binary groups, one of which receives blessed things and the other total condemnation… Jesus wept. In English, that phrase is the shortest verse in the Bible, although - as ἐδάκρυσεν ὁ Ἰησοῦς - it is not the shortest in the original languages. Nonetheless, what expressive power it has. It is certainly appropriate to recent events. What with the AUKUS deal, with its expensive, and nuclear, submarines; Nazis on the streets of Melbourne; continuing anti-trans violence; right wing Christian attacks on our own community and others; and the latest IPCC report, as if earlier ones were not enough; Jesus wept indeed. This passage has also been on my heart for some time. Not least it came to mind when I saw a recent transport ad. ‘End Extreme Poverty’ it said and it brought me up with a shock. For wasn’t that the cry of other past campaigns in which some of us have shared, such as the Jubilee campaigns to end the debt of poorer countries, and the Make Poverty History campaigns of the ‘noughties’ (2000s) with their vaunted Millennium Goals? At that time, some of us may remember, there was an ecumenical campaign, led by a former colleague of mine, called the Micah Challenge. Meanwhile, working with the National Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Ecumenical Commission, I recall being involved in our own Make Indigenous Poverty History campaign, with our own Millennium Goals, several of which have been part of the Closing the Gap initiatives since. As part of that, with an Aboriginal Christian leader, I co-wrote a little reflection on the Gospel story we heard this morning. Yet are we that further forward on many First Nations issues too? Well may we say Jesus wept. Where though is the pathway to life?  There was once a monk who, whenever he passed a mirror, would look into it, wink, and say: ‘so, you old rogue, who are you today, and what are you up to?’ It is a lovely example of what, at its best, today’s queer theology asks. It is at the heart of what Mark Jordan was saying in our contemporary reading today (‘In Search of Queer Theology Lost’). In a striking manner, it also helps lead us into this week’s great Gospel story of the Transfiguration and its meaning(s) for us. For the monk, queer theology, and our Gospel, each challenge us to deeper, more refreshing, ways of living and understanding life and faith. Each disturbs settled identities. Each offers us fresh insight into God: into divine Love and Be-ing, which can never be confined to any one identity, time or place. As one of my favourite memes has it, ‘God is always transitioning’ – or at least, our understanding of God. As, and when, we grasp that, we also share in transfiguring Love… How do you regard dragonflies? In the poem we heard earlier (As Kingfishers Catch Fire), the poet Gerard Manley Hopkins not only encourages us to be like them, but, in so doing, to be like Christ. Not everyone has always agreed however. In early colonial Australia for example, white fellas tried to kill dragonflies, just as they/we tried to kill so many other life-giving things that they/we did not understand. Those early colonialists saw dragonflies flying around and landing on their valuable horses, and they saw the horses moving and flicking their tails. So they thought the dragonflies were biting and making them crook. The colonialists were making things worse. The dragonflies were actually eating the mosquitoes and the gnats that were troubling the horses. They were life-givers, saviours even, not devils in disguise. In so many positive ways, dragonflies are thus evocative symbols for transgender people today. For, on this Transgender Day of Remembrance, we do well to attend to how bearers of light have been treated as embodiments of darkness. We do well, as our Gospel today (Luke 23.32-43) reminds us, to remember how Jesus was not crucified alone, and how others are also crucified today. And above all, we do well to affirm that it is only in recognising the light, in strange places, that we find salvation and hope for us all…

How do we picture transfiguration? Do you like the transfiguration mandala of Jack Haas for example? It is better than many as a prompt for reflection today. For the story, symbol, and spirituality of Christian transfiguration is rich and profound. Yet it can be a puzzle and portrayed in very limited dimensions, and can then seem quite distant to some of us. Let me therefore offer four pathways into the reality and meaning of Christ’s Transfiguration: four pathways on the model of the spirituality wheel of which Penny Jones spoke to us a few months ago, and to our Ministers Retreat this week. For transfiguration, as Jack Haas suggests, is like a biblical mandala, of enriching colour and creativity for our lives: a kaleidoscope revealing divine transforming love…

photo: United Nations ‘Towards a Planet-wide Culture of Non- Violence’ photo: United Nations ‘Towards a Planet-wide Culture of Non- Violence’ One of my favourite stories of transgender resistance to oppression comes from India. A group of hijra people were being harassed and humiliated. Of course, this was/is nothing new. Whilst hijra have their gender officially recognised on the Indian subcontinent, they are outcasts among outcasts, typically living on the margins, in the very poorest quarters, and they stir a range of reactions in others. Like all marginalised people, behind their own remarkable brave lives lies terrible and very real fear, and many sad stories: of the sex trade and exploitation, of cruel and/or dangerous castrations, of being cast out and shamed.[1] In one community this shaming grew intolerable. Exclusion, humiliation and actual physical and sexual violence grew exponentially. What could the hijra do? The law, politicians, even religious leaders, did not care. They were actually deeply complicit. Then, after one particularly awful day, the hijra hatched a plan. In the early hours of the morning, after stripping off their undergarments, they would walk, en masse, to the houses of the worst abusers, rattling pots and pans, bells and whistles, and anything they could put their hands on, seeking to wake up the whole neighbourhood, and make the maximum impact. This they did, raising a mighty commotion. Then, they waited whilst the worst offenders, particularly the leading fathers of the community, opened their doors and windows, and came out to see what the terrible din was all about. Standing in line, shoulder to shoulder, the hijra together then took hold of the hems of their dresses, and, with an extraordinary shriek and song of pride, lifted them up, and displayed their genitalia, in all their glory. All those who watched on were taken aback, not only with shock, but with shame. For the hijra had turned the tables on them. The shame now rested on those who were rightly shameful. The powerless had, if only temporarily, transformed the powers that oppressed them, into tools of life and liberation...  ‘The Body doesn’t lie’, they say. Well, certainly it can powerfully reveal and prompt us to the truth. Years ago, for example, I remember a yoga teacher asking me to curl up into the foetal position and give myself a hug, expressing my love for myself. But I simply couldn’t manage it. I took up position, but my arms just wouldn’t do it. Even when I actively exercised my mind to give myself the appearance of a hug, my body would not obey. For you cannot simply command love. It has to be received, acknowledged, and embodied. Or, to put it another way, love has to be breathed in and breathed out. All of this takes us to the heart of Jesus’ teaching about the commandments (in Mark 12.28-34), and to the core of the Biblical tradition… |

Authors

sermons and reflections from Penny Jones & Josephine Inkpin, a same gender married Anglican clergy couple serving with the Uniting Church in Sydney Archives

June 2024

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed