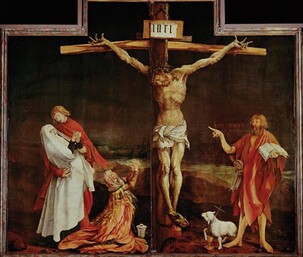

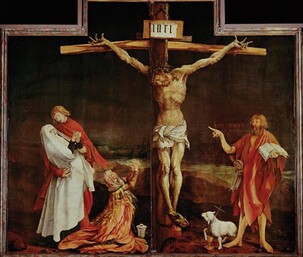

What kind of a crucifixion do we share in on this Good Friday? Is the cross a threat, a judgement, or even a weapon? Is it simply a site and symbol of death and destruction? Or is it a pathway of transformation, for us and for our world? To help us enter it as a pathway of loving transformation, I want to offer a few words around four different images of crucifixion, which may support us in our spiritual journeying today. Each is an image from the suffering of the last century of our modern world. Each, in different ways, represents the crucifixion afresh, and encourages us to know transformation. Let me first however, in introduction, share this great image of the crucifixion from Matthias Grünewald, painted for the Isenheim Altarpiece in the hospital chapel of St Anthony’s monastery. What do you see in it?...

0 Comments

image: by Suzanne D.Williams on Unsplash image: by Suzanne D.Williams on Unsplash As a pioneer female priest, one of my wife’s achievements was becoming the first female Rector of the parish of Stanhope, sometimes known as ‘the Queen of Weardale’, high up on the roof of England. She added to a line going back to the year 1200, including some famous names in church history. For whilst, financially and in other ways, ministry in remoter rural areas is challenging today, centuries ago Stanhope was known as the richest living in the north of England for clergy. This was because, way back then, the Church of England drew tithes from local people, who, in the Durham Dales, were chiefly miners and poor farmers and agricultural workers. Not for nothing was this then a significant contributor to the Dales, and County Durham as a whole, becoming strongly Methodist. There is a wonderful little story however about one of my wife’s distinguished predecessors, Joseph Butler. Butler not only became Bishop of Bristol and then of Durham, but, alongside helping to develop 18th century economic theory, he is best known as one of the leading theologians of the day: so much so that the Church of England commemorates him each year on 16 June. Now Butler had been head chaplain to King George II’s wife, Caroline. Some while after he had moved to Stanhope, the Queen therefore asked around the royal court. ‘does anyone know what has happened to Butler? Is he dead?’ ‘No, ma’am’, came back the reply by one in the know, ‘he is not dead, only buried’. ‘Not dead, only buried’: what a wonderful phrase, and one resonating both with our Gospel reading (John 12.20-31), and with our reflections on Celtic Christianity this morning… Jesus wept. In English, that phrase is the shortest verse in the Bible, although - as ἐδάκρυσεν ὁ Ἰησοῦς - it is not the shortest in the original languages. Nonetheless, what expressive power it has. It is certainly appropriate to recent events. What with the AUKUS deal, with its expensive, and nuclear, submarines; Nazis on the streets of Melbourne; continuing anti-trans violence; right wing Christian attacks on our own community and others; and the latest IPCC report, as if earlier ones were not enough; Jesus wept indeed. This passage has also been on my heart for some time. Not least it came to mind when I saw a recent transport ad. ‘End Extreme Poverty’ it said and it brought me up with a shock. For wasn’t that the cry of other past campaigns in which some of us have shared, such as the Jubilee campaigns to end the debt of poorer countries, and the Make Poverty History campaigns of the ‘noughties’ (2000s) with their vaunted Millennium Goals? At that time, some of us may remember, there was an ecumenical campaign, led by a former colleague of mine, called the Micah Challenge. Meanwhile, working with the National Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Ecumenical Commission, I recall being involved in our own Make Indigenous Poverty History campaign, with our own Millennium Goals, several of which have been part of the Closing the Gap initiatives since. As part of that, with an Aboriginal Christian leader, I co-wrote a little reflection on the Gospel story we heard this morning. Yet are we that further forward on many First Nations issues too? Well may we say Jesus wept. Where though is the pathway to life? Christmas-time is so often a confluence of loss and gain. So many of us find that good and tough memories are tangled up. My parents died a year ago this weekend, just as a new child was conceived in my immediate family: a child who will therefore be a new gift among us this Christmas. Yet it is hardly the first time that death and birthing have been entwined. Reflecting on that helps me better understand today’s Gospel and not least Mary’s extraordinary cry of justice, and of joy. As Alla Renee Bozarth brilliantly expresses it in her poem Annunciation, it is a cry of subversive angelic power. No wonder the three large ‘queer’ angels we will shortly welcome from Lismore’s LIghtnUp project are entitled Courage, Compassion, and Joy. For, as Lismore’s wonderful community artist Jyllie Jackson has identified, Courage, Compassion and Joy are core life-giving elements, not only to Queer Pride. They also, vitally, flow out of the Gospel and Magnificat of Mary, and, as Jyllie suggests to us, they are at the core of what the Way of Jesus, and our particular community, is and can be…

Visitación, detail from mural at Casa Ave Maria in Managua, Nicaragua Visitación, detail from mural at Casa Ave Maria in Managua, Nicaragua How do you relate to Mary in our Christian tradition? Even mentioning her name opens up a host of feelings and thoughts for so many. As the Danish literary historian Pil Dahlerup rightly said, in an article entitled ‘Rejoice, Mary’: No woman and no deity in the Middle Ages attracted the poets like the Virgin Mary, mother of Christ. It is, however, hard to read what the poets write about Mary; we are inhibited by prejudices that block our understanding of what the texts are actually saying. Protestants dislike her because she is attributed divinity. Male chauvinists dislike her because she is a woman. Feminists dislike her because she is a woman in a way of which they disapprove. Nationalists dislike her because she represents an alien element in terms of creed and idiom. Marxists dislike her because they do not see her (in the North) as a figure of the people… Despite this, we cannot avoid Mary in Christian faith. Not least, although women and their lives and gifts are so few and highly gendered in the Bible, Mary simply cannot be erased. So what do we make of her today?... The word ‘Emerging’ has come to the fore recently. It expresses well where many people of spirit are in our lives and faith journeys. Emerging is also a central aspect of our world as a whole at present, as we engage with the uncertainties and opportunities of possible futures with and beyond Covid-19. Meanwhile, more broadly, Emergence is a powerful theme in much contemporary thinking about science, society and philosophy. Lively questions therefore surround, and stir in us. What kind of a world is it in which we live, and might like to live? What is coming into being, not least in spirituality? What difference might these things mean to our lives and our faith journeys? In other words, to reconnect with the Christian story, what, again, does Resurrection mean for us? For, as our Gospel reading today once more reminds us, Resurrection is an invitation into a more mysterious future, in the power of Love. Consequently, in the next few weeks of our Easter season, let us enter into into deeper reflection on what is emerging in us, and in our journeys with others. We begin with the body. Our Gospel today speaks of Thomas, with the other disciples, trying to make sense of Christ’s risen body. What difference did that make to them? What might the resurrection of the body mean to us?...

“He breathed on them and said, ’Receive the Holy Spirit’”

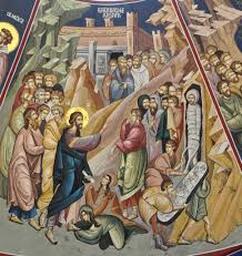

- Oh my: it’s to be hoped they were all at 1.5metres distance and wearing masks!...  By now most of us have seen the photos of many notable landmarks, especially in Europe, virtually deserted. Among them, and symbolic of the tragedy that has come upon northern Italy, is the great St. Mark’s Square in Venice, dedicated to that most audacious saint whom we commemorate today. Everywhere in Venice you see the symbol of the winged lion, his paw on the gospel; the symbol of Mark the evangelist - the gospel writer. Mark wrote the first gospel. That sounds quite commonplace to us two thousand years on. We know that the other two synoptic writers, Matthew and Luke, took his work as their model and added to it, but Mark wrote the first one. The very act of writing was extraordinary. He did something that had never been done before. There had been other kinds of similar writing – lives of the great heroes of Greece and Rome – but no one had ever written a gospel before. It was an audacious act to try and set down what had happened and who Jesus was. Mark was brave and did something entirely new. We don’t know for sure, but it seems likely that he wrote his gospel around 70AD - the time that the first Christians were being expelled from the Jewish synagogues and undergoing persecution following the fall of Jerusalem. That event was cataclysmic at the time. He writes because he feels he has to. He writes because there is a danger that if he does not the story will be lost, perhaps forever. The threat of imminent death inspires extraordinary acts of bravery, as we are seeing in the world today. Fear can beget bravery. However, fear can also beget timidity and we see that in the gospel story we just read. It is thought that Mark actually ended his gospel at verse 8 ‘and they said nothing to anyone for they were afraid’ – in the Greek text it actually ends with the tiny word ‘gar’, meaning ‘for’. The first gospel ends with a tender little conjunction – a joining word. It was for the pens of later writers to finish the text – and to join Mark’s brave, first testimony, to the future trajectory of the church, commissioned by their version of the risen Christ to ‘go out and proclaim the gospel’. Mark told the truth, tender as a young leaf – at first the wonder, the audacity of the resurrection could not be believed. It was just too new; too incredible to be trusted. We like Mark, are facing dangers. We like Mark, are being challenged to do things we have never done before. We like Mark recognize that the way out of here requires hope and trust in things we cannot yet fully see or believe. Can we, as individuals, as churches, as society, be like Mark? Can we be brave enough to attempt the new, and bold enough to hold the tender green leaf and not crush it? For this is God’s call to us in our time. Amen. by Penny Jones, for St Mark's Day, celebrated Sunday 26 April 2020  Our Gospel reading today (John 11.1-45) is the extraordinary story of the raising of Lazarus – a story of resurrection not just for the future, but into every day, earthly material life. I want us to concentrate on the three commands that Jesus gives in this story. Over the coming week you might like to ponder each in turn for a couple of days, and see how God speaks to you and the circumstances of your life through each one. The three commands are these: Take away the stone Come out Unbind him and let him go... |

Authors

sermons and reflections from Penny Jones & Josephine Inkpin, a same gender married Anglican clergy couple serving with the Uniting Church in Sydney Archives

June 2024

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed