photo by Mark Konig on Unsplash

photo by Mark Konig on Unsplash Today’s Gospel passage is one of a series of stories in Mark’s Gospel with disturbance and controversy involving Jesus. Indeed, in next week’s Gospel, we will continue to hear about Jesus not only exhibiting divine power through healing but also ‘casting out many demons’.[1] Let us consider more closely next week what the biblical demonic might mean to us in our world today. For the moment, it is important to understand that, for Mark and the community for which he wrote, the demonic was all part of false forces, structures and energies which were claiming authority over people’s hearts and lives. Therefore, central to Mark’s whole Good News is the affirmation in today’s passage that Jesus’ works are about authority. Whether it is healing, teaching, or exorcising the demonic in its various forms, all point to the presence of the divine, true authority, bringing about the reign of shalom. For Mark’s Jesus may, at first reading, seem to be more down-to-earth than the Jesus of John’s Gospel, which has all those ‘I am’ statements. Yet, if, Mark’s is thus more of a ‘low’ Christology, the Christ of Mark’s Gospel is, in many respects, no less a figure who stands over against ‘the (ordinary) world’ and calls us to follow a different drum.

The Christ of Mark’s Gospel is certainly different from that of Luke and Matthew in this respect. Matthew, for example, presents Jesus as the new Moses, renewing the Law. Luke, for their part, seeks to make a bridge between the Judaean foundations of the Way of Jesus and the wider Gentile world, including leaders in the Roman Empire itself. Mark however presents Jesus more starkly, in much more vigorous conflict with existing authorities, whether the colonial oppressors, the religious and social leaders, or the thoughts and hearts of any group, or individual, including Jesus’ own family and followers. Mark’s, we might say, is truly the prophetic Gospel, and Mark’s Christ challenges any other authority in our world, external or internal, rather than merely relativising, critiquing and fulfilling. If we are not therefore disturbed by reading Mark’s Gospel, we have therefore really missed its point!

divine authority

Not for nothing has Mark thus been a favourite Gospel for more radical theologians, as distinct from reformist liberals and progressives. One important such contribution was made, back in 1988, by Ched Meyers, in his biblical commentary Binding the Strong Man: A Political Reading of Mark’s Story of Jesus. Indeed, the biblical scholar Walter Wink, called this ‘quite simply the most important commentary on any book of scripture since Karl Barth’s Romans.’ Now Meyers’ book is different in many ways from Barth’s. Yet they have this in common: they emphasise that truly understanding the scriptural text requires not only that its linguistic and historical contexts are explored, but that we need to wrestle with it in the light of other perspectives: including political and philosophical hermeneutical approaches, social psychology, and anthropology. As Barth put it, we are then able to hear the Word of God speaking over and into our human condition, and, like Mark’s Gospel, to receive Christ as an epiphany, or revelation, to us.

Meyer’s work remains helpful because it picks up on the prophetic, revelatory, character of Mark’s Gospel and it challenges us to see that Jesus’ words, and still more Jesus' actions, were intimately related to contemporary political and religious contexts. As I said earlier, we will, for example, hear further about Jesus’ confrontation with the demonic. If however we see this only, or even first and foremost, about individual distress, we will really have missed the point. For, as Meyer identified, Jesus’ conflict with specific instances of demonic individuals is symbolic of, and interrelated with Jesus’ conflict with the demonic political, social, and religious, forces which were imprisoning the bulk of the people and denying God’s fruitful life – shalom. Mark’s Jesus thus calls us to recognise what needs to be truly central in our lives and world, namely God’s authority. Everything else, such as various kinds of demons and healing, is ultimately illustrative of this. Which kind of authority will we then choose?

what is truly prophetic?

This brings us back to the question of discerning what is truly prophetic, and who are true prophets: a question very much central to our other reading this morning, from Deuteronomy 18. This is placed in our lectionary today as it can be interpreted as a foreshadowing of Christ, thereby viewed as a new prophet like Moses: which indeed is also one way in which Islam interprets, and honours, Jesus. Of course, that is not its original context and we risk imposing a Christian, rather than a Jewish or other, reading upon it when we see it as merely a forecast of Christ. Nonetheless, this passage, like others in our scriptures, is part of a continual wrestling with what divine prophetic words and actions look like, and how they are embodied. There are no simple answers in this. Yet we can identify some important features.

Firstly, a true prophet seeks purity of heart: for being disturbing and/or controversial is not in itself a sign of a true prophet. Nor is being prophetic necessarily about being ‘politically correct’, or on the ‘right side of history’ - whatever those things mean! There is, for example, a wonderful line in T.S.Eliot’s Murder in the Cathedral where Thomas a Becket wrestles with his motivation for standing up against his king and injustice. In Eliot’s words, Becket says:

‘the last temptation is the greatest treason/To do the right thing for the wrong reason.’

In that sense, Christ is always ‘an uncertain ally’ to any political, or other, cause. For the Christ of Mark’s Gospel challenges all authority, including our own current political and other obsessions, good as well as bad. Part of that is always to speak and act with due humility, and with mindfulness, wherever possible. For, it is again highly significant that Jesus’ confrontation with demonic powers comes after Jesus has been in the wilderness: letting go of self-interest and personal obsessions through the Spirit of God praying deeply with, and within, them.

Secondly, a true prophet is genuinely empowering of others. For that which is truly prophetic may indeed enter into, and confront, spaces which exclude and deny divine holiness and shalom. However, Mark’s Jesus is not what some call ‘oppositionally defiant’, nor prompted by desperation. Without, for example, seeking to enter deeply into a still tender subject in Ireland, the poet W.B.Yeats’ reflection on the Easter Rising of 1916 is perhaps apposite. Reflecting on the Irish martyrs who, in the face of British colonialism, famously seized the General Post Office in Dublin, proclaiming the Proclamation of the Irish Republic, Yeats reflected:

I write it out in a verse--

MacDonagh and MacBride

And Connolly and Pearse

Now and in time to be,

Wherever green is worn,

Are changed, changed utterly:

A terrible beauty is born.

Those Irish leaders were undoubtedly prophetic, but ambiguously so. For terrible violence and civil war followed, admittedly also something for which Britain must forever be ashamed. For as Yeats also mused:

Too long a sacrifice

Can make a stone of the heart...

We know their dream; enough

To know they dreamed and are dead;

And what if excess of love

Bewildered them till they died?

In our own sharing in Christ’s prophetic today, let us then also take care that we are also not bewildered by our dreams and an excess of love. And let us find ways that those who have experienced ‘too long a sacrifice’ may not have their hearts turn to stone: the fate of many combatants in many struggles today as always.

Thirdly, a true prophet shares in divine wholeness. What is truly prophetic will reflect the wholeness of God. For wholeness is the aim of a true prophet, not conflict, though this is usually unavoidable where important things are at stake. That is one reason why I always feel that it was a happy decision of our Christian forebears to include four Gospels in the Biblical canon. For Mark’s Christ rightly remains a challenge to the Western, richer, more powerful, and complacent parts of today’s Church and world. Such a Jesus is vital, speaking out and casting out the world’s demons: whether that be racism, sexism, able-ism, and homo- and trans- phobia, economic exploitation and cultural denials, colonialism, violence of various kinds, and, let us not mince words, genocide today. Yet, that Christ is only truly prophetic when they are also understood to be the healer and nurturer of life and community - and indeed the very bread, true vine, and power of resurrection - found elsewhere across all the Gospels.

telling forth God's shalom

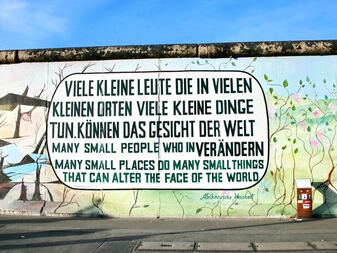

What does this then mean for us? Well, I always find it helpful to think of prophecy as forth-telling, not fore-telling: that is as enabling shalom to be named and embodied, and thereby brought forth, rather than as predicting the future. None of us can know the future, and it is usually twisting history, or scriptures, to read into them what will only later be revealed. Yet what true prophetic living can do is to enable a re-imagining of our lives and world, and to start creating that new imaginary by enacting and living into it. That is why I have put that photo on the front of today’s liturgy sheet, of words written on remains of the Berlin Wall, encouraging us to know that:

‘many small people in many small places

do many small things that can alter the face of the earth.’

In this, unafraid of other supposed authorities, but seeking to purify ourselves from our own fear and self-interest, may we share in the work of the truly prophetic we find Jesus Christ, the bearer of divine shalom. As-salamu alaykum. Amen.

by Josephine Inkpin, for Pitt Street Uniting Church, Sunday 28 January 2024

[1] Mark 1.34

RSS Feed

RSS Feed