image by Ehteshamul Haque Adit on Unsplash

image by Ehteshamul Haque Adit on Unsplash

image by Ehteshamul Haque Adit on Unsplash image by Ehteshamul Haque Adit on Unsplash Do you know the allegorical image known as 'The Vinegar Tasters'? It is related to Eastern philosophies and may be helpful to reflect upon as we end one calendar year and begin another, particularly as today’s Gospel reading offers us symbols brought to the Christ child from the East. For which gifts are we to offer at this time? What pathways are we seeking to tread into the future?...

0 Comments

image by Greg Rakozy on Unsplash image by Greg Rakozy on Unsplash In his tender and tantalising work Anam Cara, John O’Donohue wrote that: “the way you look at things is the most powerful force in shaping your life.” I want to talk about three ways of looking at things suggested by our readings today – the microscopic that allows us to appreciate our own smallness and uniqueness; the telescopic that invites us to move imaginatively towards universes beyond this one; and the cosmic that calls us to a bigger story. For story is critical and it is only through story that we shall be able to effect the extraordinary changes required by our current ecological crisis... What’s in a name? - often, a huge amount. First Nations peoples are very clear about that and the intimate relationship between naming, language more widely, culture, identity and flourishing. Other oppressed peoples know this too. Hence the suppression or promotion of different languages is so vital an issue: just look, for example, at Wales, Catalonia, Belgium or Canada. It is not simply good manners to use the language people ask of us. It is because, unless we do so, we are disconnected from layers of meaning and identity, place and community, history and, indeed, geology. Take my surname: Inkpin. This has nothing to do with writing or being a scribe, or seamstress. It comes from two ancient British words: inga and pen. Inga, in modern English, means people. Pen means hill. This tells me, and others, that I come from the people of the hill, with all the deep layers of connection this entails: to particular soil and environment; to history and culture; to others, past, present and future. Indeed, even today, there are English villages, not surprisingly on hills, with the name Inkpen. For whilst much was swept away by the two great imperial invasions of my native land, there are still fragments of British indigeneity left, and one is my surname. It is a living reminder that there are other ways of being English, and British, than what is usually asserted: there are always were, and there always will be. For when we look more deeply, the living fragments of traditional cultures in every land call us both to recognition of pain and loss, and also to fresh pathways of justice. This is part of today’s Day of Mourning. We will not find peace unless we recognise what has happened in this land - and particularly in this city; unless we repent – and much more radically than we whitefellas have so far done; and unless, in Midnight Oil’s words earlier,[1] we ‘come on down’ to the makararrata place, ‘the campfire of humankind’, ‘the stomping ground.’…

One of the puzzles Christians have sometimes set themselves is to work out what light is being referred to in the first few verses of the Bible. For, apart from modern light forms, we are so used to thinking of light from the sun and moon, which, in the Genesis account, are only created later. Various possibilities have therefore been suggested by the great theologians. Some (such as Ephrem of Syria) have thus suggested the light was a pillar of fire, or (like Basil of Caesarea) that the essence of the sun without its actual substance, or even that the light came for the angels (in the case of Augustine of Hippo). However, in so far as we might respond, I think I would go with the Orthodox Church’s understanding of ‘the uncreated light’ of God in Godself. For, when we come to the first chapter of Genesis. we are speaking here of divine mystery, depth, purpose and ultimate meaning, not literal or even limited symbolic explanation of Creation. Rather, like our second reading today (For Light by John O’Donohue), the nature of Genesis chapter 1 is poetic and prayerful, seeking to lead us into sacredness. For above all, such texts are designed to renew our sense of wonder and participation in divine creation and our role as priests of God’s Creation…

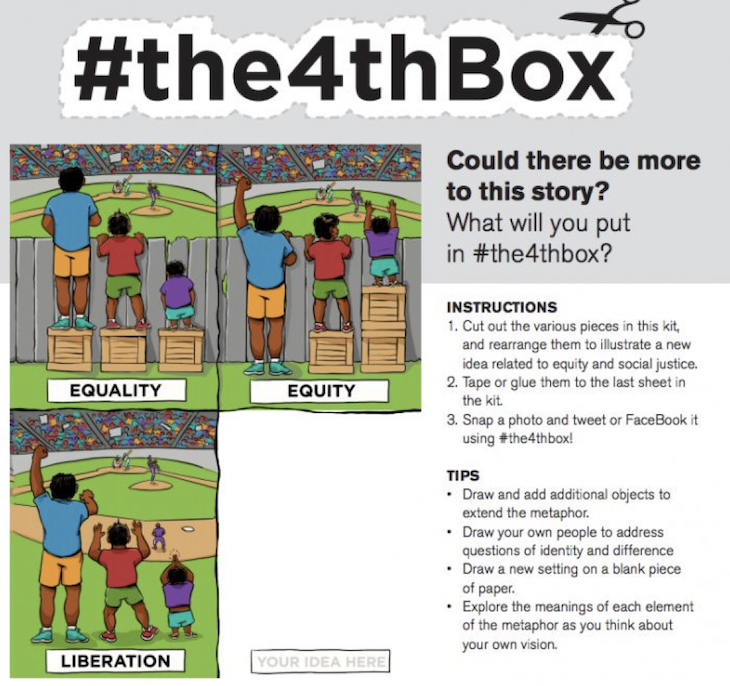

In recent years some of my Aboriginal friends have said to me that they do not really believe in the Australian concept of Reconciliation and some of the activities, like Reconciliation Action Plans, which have accompanied it. Meanwhile some Church leaders have said to me that they do not see much point in engaging actively in ecumenical endeavours. So why, we might ask, are we marking the Week of Prayer for Reconciliation and the Week of Prayer for Christian Unity this morning? Actually I did wonder about changing the title on the front of our liturgy sheet today to ‘Prayer for Just Relationships and Communion in Christian Diversity’. That, for me, would be at least part acknowledgment of the difficulties of the words Reconciliation and Christian Unity and the need for re-imagining as well as building on the good work of the past. However I have left Reconciliation and Christian Unity in the title for the present, so we honour where we have traveled. Nonetheless, as we hear our two readings this morning (from Revelation chapter 22 and John chapter 17), we do well to reflect more deeply on the words and constructions we may use in order that we share in more fruitful pathways for our work together with others. For that purpose I also offer you the cartoon meme entitled the #4thBox, as an encouragement to deeper prayer, more imaginative reflection and more creative action…

Good morning! It is a delight to be back here in Pitt Street after several weeks away on personal ‘sorry business’ and study leave. In the context of the continuing pandemic, it has certainly been what some might call an ‘interesting’ time, marking an important watershed in my own life and that of my wider birth family. In offering some reflections today, I would therefore like to begin by expressing my deep gratitude for the many, many. wonderful expressions of support from members of our Pitt Street community, and for the prayers which have been offered. I continue to be so grateful for the gift of loving relationships I am given as part of our life together, and I look forward to their further and deeper unfolding in the days to come. For relationship is such a core element of our lives, and never more important than at times of loss, grief, challenge and growth. As such, it is so absolutely foundational to the Day of Mourning we mark today, as well as to the trials of the pandemic world with which we continue to journey, and the struggles of our own particular lives. In the light of these things, my own recent and continuing journey, and of our readings today, I offer up relationship as one of three words which might be central to our considerations at this time.

Growing up, even as a little child I was fascinated by what was then known as the English Civil War (although, to be accurate historically, this is now rightly recognised as several different wars across the islands of Britain and Ireland). It was a bitter and brutal period, culminating in the judicial trial and execution of the King. For this was a powerful revolution. Indeed it saw the establishment of a republic, the Commonwealth and Protectorate under Oliver Cromwell. Moreover, in that latter period there was also an extraordinary flowering of truly radical religious and political life and thought. That, I think, was what especially drew me into the study of history. For the origin of many liberal democratic things we take for granted lie there – for example, the insistence on no taxation or legislation without representation, on regular elections, fixed parliamentary terms, equal votes, and, vitally, on religious freedom for different types of groups, particularly the marginalised. Indeed, Cromwell even reopened England to the Jews, who had been banned for centuries. For his supporters were also part of the movements which helped create Congregationalism, the original founding tradition of Pitt Street Uniting Church...  photo: Harry Quan on Unsplash photo: Harry Quan on Unsplash This morning, I’m going to share this Reflection as a conversation with Penny, on how we feed on God through experience today. For, as we reflect upon John chapter 6 once more, where, and what, is the Bread of Life for us in the midst of some of our greatest challenges? Through whose eyes are we looking at this?...  Battle of One Tree Hill memorial cross - by Uncle Colin Isaacs Battle of One Tree Hill memorial cross - by Uncle Colin Isaacs One of things I’m thankful for in my years of ministry is the memorial cross I helped install in the Warriors Chapel in St Luke’s Church Toowoomba. It remembers the battle of Meewah, otherwise known as One Tree Hill, or Table Top Mountain. This was part of the devastating Frontier Wars in this country. It was led, on the Aboriginal side, by the great warrior Multuggerah and part of deep, and extraordinary skilled, schemes of resistance. It is intimately connected to the continuing debilitating impact of colonial dispossession. Without remembering and reconciling, such deep wounds endure. Yet so little of this story is named or reflected upon. In contrast, on this day (25 April), the awful pain of the Gallipoli landings is recalled: often, in recent years, with exceptional noise and attention. Why is it that some stories become enduring, and even ever enlarged, myths, whilst others, no less historically significant, are hidden or left to fester? How do we best make peace with our past? And how do myths and memories of faith distract or assist?  When I was young, parts of the country in which I grew up literally blew away. Living in Lincolnshire, one of England’s greatest agricultural counties, I could see this whenever I traveled. For I grew up as a child at the time of the greatest destruction of England’s hedgerows, many of them very ancient. Indeed, hedgerows are, as the Campaign to Protect Rural England has put it, ‘the most widespread semi-natural habitat in England’, and, more poetically, ‘the vital stitching point in the patchwork quilt of the English countryside’.1 They not only provide character, but essential life to all kinds of creatures, and help protect the soil itself without which there can be no sustainable farming yields. As a child however, I would see such features regularly ripped away, and a vast desert of landscape created, with vital topsoil whirling up in dust storms and carried away. Such soil frequently blinded us, reflecting the blinkered industrialised agricultural thinking which had produced it. It was an early lesson to me of how if we mistreat the land out of which we come and are fed, we also destroy ourselves. How then are we to live, without seeking the forgiveness of the land itself, and renewing creation together?... |

Authors

sermons and reflections from Penny Jones & Josephine Inkpin, a same gender married Anglican clergy couple serving with the Uniting Church in Sydney Archives

June 2024

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed