|

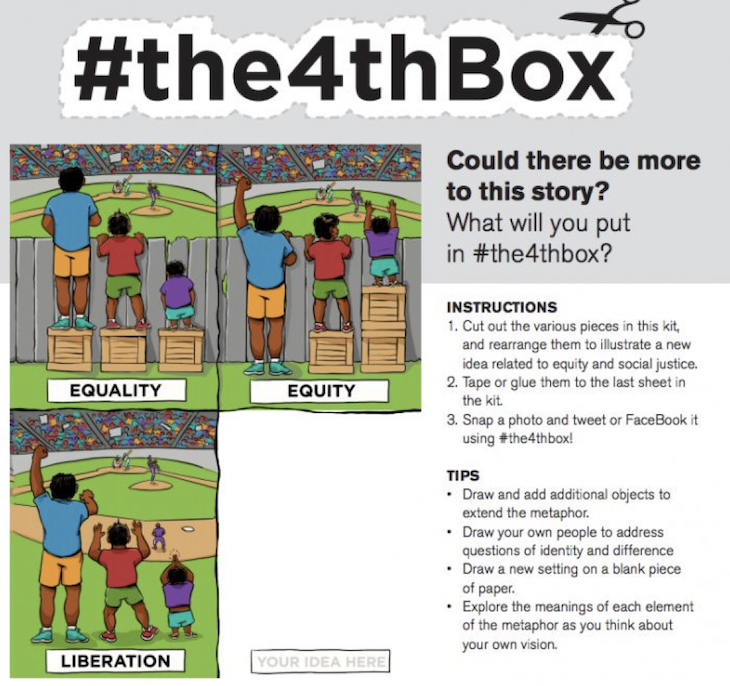

In recent years some of my Aboriginal friends have said to me that they do not really believe in the Australian concept of Reconciliation and some of the activities, like Reconciliation Action Plans, which have accompanied it. Meanwhile some Church leaders have said to me that they do not see much point in engaging actively in ecumenical endeavours. So why, we might ask, are we marking the Week of Prayer for Reconciliation and the Week of Prayer for Christian Unity this morning? Actually I did wonder about changing the title on the front of our liturgy sheet today to ‘Prayer for Just Relationships and Communion in Christian Diversity’. That, for me, would be at least part acknowledgment of the difficulties of the words Reconciliation and Christian Unity and the need for re-imagining as well as building on the good work of the past. However I have left Reconciliation and Christian Unity in the title for the present, so we honour where we have traveled. Nonetheless, as we hear our two readings this morning (from Revelation chapter 22 and John chapter 17), we do well to reflect more deeply on the words and constructions we may use in order that we share in more fruitful pathways for our work together with others. For that purpose I also offer you the cartoon meme entitled the #4thBox, as an encouragement to deeper prayer, more imaginative reflection and more creative action…

0 Comments

Three things immediately struck me in recently moving back to work again in the centre of Sydney. Firstly, so many of the high buildings had either grown even higher or had multiplied in number. Secondly, particularly in the adjacent areas north and west of Pitt Street Uniting Church, different Asian shops and cultures continue to grow in number. An official Koreatown now sits close to Chinatown, and other presences, including Malaysian, and particularly Thai, are not far behind. Thirdly, in the suburb where I live, each park has an acknowledgement of country, including the prominent words Budyeri gamarruwa – ‘welcome’ in Gadigal language. Each of these things are redolent to me of both the challenges, and the promise, of Pentecost today. For if we are to receive the Spirit of God more fully - replacing hearts of stone with hearts of flesh, and becoming one body in this land - these are part of the journey we make…  One of the most memorable voices of my English schooldays was that of the great cricket commentator John Arlott. He reported on many things, and was also a poet, wine-connoisseur, hymn-writer, part time politician, anti-apartheid spokesperson and renowned host of dinner parties. His distinctive radio tones and brilliant turns of phrase illuminated English summers and some other special occasions, notably the great Centenary Test Match in Melbourne in 1977. Thousands of miles away I remember being curled up through the night listening under the covers to John’s words. His descriptions were typically unforgettable: such as that of the scene of Dennis Lillee’s destruction of the English first innings, where, he said, even the ‘seagulls were standing in line like vultures’, and also Derek Randall’s heroic second innings fightback – an innings as inimitable as John’s own expressions. Gordon Greenidge, the great West Indian batsman, even named him ‘the Shakespeare of commentators.’ Above all, however, I will always cherish John Arlott’s vigorous standing up for our common humanity, not least over apartheid. He had learned to move on from his English colonial upbringing from Indian cricketers, not least the wonderful Vijay Merchant. Famously then, he was involved at the forefront of cricket’s anti-apartheid struggles. Indeed, as early as 1948, visiting South Africa, he refused to fill in the section marked ‘race’ on the departure form, except to put the word ‘human’. ‘What do you mean?’, said an angry immigration officer aggressively. ‘I am a member of the human race’ came back the reply. Eventually he was just told to ‘get out’. How I wonder would John Arlott fare today with resurgent racism, nationalism, and the exclusivism of so many immigration policies? What price human unity today? What, in this Week of Prayer for Christian Unity, does faith have to contribute?...  Over the last few weeks I have had the wonderful, if challenging, experience of sharing in leading the God, Humanity and Difference course at St Francis’ College. This has included looking at a wide range of human differences: including those of race, disability, gender, sexuality, faith, culture, history, and socio-economic position. We have heard from a variety of voices from across our Church and world: including Canon Bruce Boase (as an Aboriginal priest, as we explored Reconciliation issues) and, not least, Elizabeth and Ann from our very own congregation here (as we explored faith issues related to disability). In addition, we have been blessed by the insights of the rich mix of backgrounds and experiences within the class itself, including students originally from Sudan and Korea. Sometimes this has meant that we have met fresh questions and ideas which will require some working out. For our God-given human differences are not always easy for us all to live with. We can see that clearly in some of the conflicts and controversies of our Church and world today. Yet, as we have discovered in our course this semester, if we hold them prayerfully, and work with them with intelligence and compassion, they are powerful gifts to us for healing, new life, and flourishing together. For properly to hear each of us, speaking our own witness to God in our own way, is to let the Holy Spirit fly free in fresh experiences of Pentecost…  Shall we agree to disagree? No, we won’t. That has been the answer to that question through much of human history, hasn’t it? Isn’t it still the answer today in many places and in many parts of our own lives, including within the Anglican Communion today? As human beings we really struggle with the idea of unity on any other basis than what seems good, and restricted, to us. We see this played out, time and time again, in politics, in the great events of the world, in contested issues within the church and other community groups, and in our own family and personal lives. So praying for Unity and Reconciliation, as we do today, is a real challenge. For what kind of unity and reconciliation are we actually praying? Is it that our will, or God’s will, be done? Is a different answer to the question ‘shall we agree to disagree?’ part of this? I have been reflecting on these things over the last few days in relation to three key issues which have touched my heart: namely the terrorist bombing in Manchester, the campaign for Marriage Equality (a keynote Brisbane meeting of which I attended this week), and Australian Reconciliation. Each raise thorny problems if we look at them in certain ways. Yet they offer us encouragement to true unity with genuine diversity if we regard them in other ways. For how do we picture unity? It makes all the difference how we see it… A few weeks ago our Toowoomba Catholic bishop was interviewed by several national TV and other media outlets. He did a wonderful job in sharing our Christian concern for our neighbours, particularly for our Muslim neighbours whose mosque had been set on fire. You would have thought that all other Christians would have been grateful to him, wouldn’t you? After all, loving our neighbour, whoever they are, is at the very heart of the teaching of Jesus. Strangely however, he told me that someone complained, calling him Antichrist. Oh dear, I replied, it sounds as if the worst spirit of the Reformation is alive again! For that kind of language and attack on fellow Christians was very much part of the Reformation and much of Christian history. Indeed, it helped promote similar kinds of warfare and bloodshed which we now see consuming parts of the Islamic world, where believers kill fellow believers, as well as others, in the name of their particular kind of faith. No wonder many people therefore have difficulties with religion as a whole. Even where there is no physical violence, many religious people can still sometimes display distressing self-righteousness and judgemental attitudes towards others. For this reason, if nothing else, we surely need to continue to pray for Christian Unity and for that peace of Christ which passes all understanding.

This week’s readings certainly challenge us to explore what it means to live in love and unity together. This is especially the case with our second reading. Somewhat unusually, this is also almost the same text as our second reading last week. Certainly it deserves attention. For this reading is drawn from the First Letter attributed to John: a letter which takes us deep into the intense Christian disputes and theological divisions of the first two centuries of Christian Faith. For make no mistake, Christians have always had arguments with one another...  by the Revd Dr Jonathan Inkpin, Pentecost evensong at St John's Cathedral Brisbane, Sunday 8 June 2014 ‘Come out from behind that thing!’ – the Aboriginal elder’s voice rang out powerfully as I was about to begin the Decade to Overcome Violence launch in Alice Springs. She was objecting because I was behind a lectern: another whitefella, as it were, standing over or apart from her. As it happened, in what followed, every blackfella who spoke also headed behind the lectern. I guess therefore it was probably that elder’s own personal issue. Yet I have never forgotten it. For, in a way, following feminist pioneers, it was a lived experience of what Indigenous scholars (such as Denis Foley, Martin Nakata and Aileen Moreton-Robinson) call ‘standpoint theory’. Standpoint theory is a postmodern method for analysing inter-subjective and ethical discourse. For a standpoint is a place from which one sees the world. It thus helps direct both what we focus on as well as what is obscured. The specific circumstances of our standpoint then determine which concepts are intelligible, which claims are heard and understood by whom, and which reasons and conclusions are understood to be relevant and forceful. Now, like any approach, standpoint theory is not without weaknesses. It risks, for example, generalising the experience of different peoples, and it risks suggesting an overly ‘essentialist’ character of particular genders, races, or other identities. Yet it is a powerful means in which marginalised groups can challenge the status quo. Indeed, as the feminist theorist Sandra Harding put it, it helps create ‘strong objectivity’, or strong inter-subjectivity. For when the perspectives of the marginalised and/or oppressed are included, we have more objective, or deeper inter-subjective, accounts of the world. This is vital to a richer, and more life-giving, ethics. Spiritually speaking, standpoint reflections also lead to a richer ethical and doctrinal expression of Pentecost. For, in Pentecost, the Spirit of God is embodied, enlivened, and expressed through all created voices. As God’s voice puts it, through the prophet Joel, in our first reading tonight, ‘I will pour out my spirit on all flesh’: on old and young alike, male and female, not least slaves; and, the passage goes on to say, also through the more-than-human environment, by ‘portents in the heavens and the earth.’ True Pentecostal experience, it seems, is about true inter-subjectivity. All creation’s standpoints are voiced, held together, and contribute to the whole. Pentecost is thus a basis for a holistic, fully environmental, ethics. For Pentecost is so much more than we have often made it...  by Jonathan Inkpin Our Gospel reading for Sunday 1 June concludes with the words of Jesus: ‘Holy Father, protect them in your name that you have given me, so that they may be one, as we are one’ (John 17.11b). How appropriate this is, as we come to World Environment Day this week, in the midst of the Week of Prayer for Christian Unity! For in words which resonate wonderfully with Jesus’ prayer, our UN Secretary-General, Ban Ki-Moon, also calls out, saying: "Planet Earth is our shared island, let us join forces to protect it." The UN Secretary-General’s call for global unity is not surprising. It is only recently that we heard of more catastrophic flooding in the Solomon Islands. Yet this is but the latest of a series of environmental disasters and challenges which are faced by the small island nations of our world. This year’s World Environment Day theme of Raise your voice – not the sea level is therefore a very fruitful one for enabling us to ponder the nature of and challenge of Christian unity. For it can lead us into a deeper awareness of our interconnectedness with all of God’s Creation, and, in particular, with the hurts and hopes of our brothers and sisters in the small island nations of our world... |

Authors

sermons and reflections from Penny Jones & Josephine Inkpin, a same gender married Anglican clergy couple serving with the Uniting Church in Sydney Archives

June 2024

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed