image: Brandy Martell, 400 block of 13th St near Frankland St, Oakland

image: Brandy Martell, 400 block of 13th St near Frankland St, Oakland

image: Brandy Martell, 400 block of 13th St near Frankland St, Oakland image: Brandy Martell, 400 block of 13th St near Frankland St, Oakland ‘Tell all the truth', wrote the poet Emily Dickenson, 'but tell it slant’. For ‘The Truth must dazzle gradually/Or every one be blind.’[1] That is pretty much Mark’s Gospel’s account of resurrection, isn’t it? Whilst other resurrection stories were attached later, the two earliest, and arguably the best, manuscripts of Mark’s Gospel stop abruptly at verse 8 of chapter 16, with women fleeing from an empty tomb and ‘saying nothing to anyone, for they were afraid.’ Furthermore, the text simply stops in mid-sentence, with the little preposition which means ‘for’. Mark’s Gospel, at least, is clear that resurrection is both truly astounding and impossible to convey straightforwardly. For how do we describe resurrection? How do we communicate resurrection? How do we live resurrection? The nature of resurrection is that it involves strange truths of transformation: which require, like so much great art, ‘telling it slant’; which rest on mystery; and which revolve around deep, lived, experience. For art, mystery, and experience: these three things are at the heart of the strange truths of resurrection we exult in today, as witnessed to by our readings and key images this morning, and the continuing life of you and I, and all who follow Christ…

2 Comments

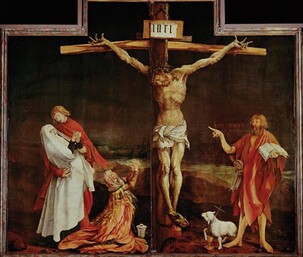

What kind of a crucifixion do we share in on this Good Friday? Is the cross a threat, a judgement, or even a weapon? Is it simply a site and symbol of death and destruction? Or is it a pathway of transformation, for us and for our world? To help us enter it as a pathway of loving transformation, I want to offer a few words around four different images of crucifixion, which may support us in our spiritual journeying today. Each is an image from the suffering of the last century of our modern world. Each, in different ways, represents the crucifixion afresh, and encourages us to know transformation. Let me first however, in introduction, share this great image of the crucifixion from Matthias Grünewald, painted for the Isenheim Altarpiece in the hospital chapel of St Anthony’s monastery. What do you see in it?...  I thought it might be helpful this morning to bring along a favourite bowl of mine. It was made by an artist friend Kerry Holland, whose paintings and bowl sculptures on the theme of The Visitation is currently on exhibition in Pitt Street Uniting Church. She also made this one, which she gave to me as a gift when I came out as transgender, affirming my authentic gender identity a few years ago. It is precious to me for that reason but also because, like all of Kerry’s bowl sculptures it is unique, with its own particular shape, story, and constellation of colours. In that sense, it is like each human being: an exquisitely unique and special divine creation. The more I reflect upon that, and upon the nature of a bowl itself, the more I am also drawn into the love of God. So I would like to share with you some ways in which each of us might helpfully use a bowl as a prayerful way into appreciating ourselves and others and holding together what can easily be misused in the Gospel parable (Matthew 25.31ff) which we heard read just now. For, whilst that passage is in some ways quite straightforward in the challenge it offers us, it is also presents some questions, particularly in the way it divides people into two black and white binary groups, one of which receives blessed things and the other total condemnation…  Un Mundo, by Ángeles Santo, Museo Reina Sofia Un Mundo, by Ángeles Santo, Museo Reina Sofia What value does the book of Revelation have for us, especially in the face of ecological crises? My guess is that most of us have not spent too much time on the Bible’s last book. Some people of course have, including those looking for a special secret code to life and history, and those puzzling out different timetables for Christ’s second coming. Such interpreters however typically have little concern for ecology, and some even welcome signs of environmental apocalypse. Faced by the strangeness of John the Divine’s visions, we may therefore be tempted to dispense with the book altogether. Yet that would be a mistake. For, as this morning’s reading (ch.12 vv. 1-9 & 13-17a) illustrates, truth and light can be received in the strangest places…  Sower at Sunset, by Vincent Van Gogh Sower at Sunset, by Vincent Van Gogh One of the particular spiritual sayings I often return to is from the Irish poet-priest John O’Donohue: ‘When you see God as an artist, everything changes.’ We are so used to hearing about God as a law-giver, an instructor, and/or a judge, that we can so easily miss this central truth of living faith. Of course, law and specific guidelines and moral codes can help us in our lives. Yet we have often so over-emphasised the will, and judgement, of God almost to the exclusion of the imagination and creativity of God. That is one reason to look at Van Gogh’s great painting of the Sower at Sunset alongside the parable of the Sower and the Seed in today’s Gospel. For we are helped by viewing the parable as art. Indeed, we might see Jesus’ life and teaching as so much more a great artwork than a set of rules, never mind a clear blueprint for living. Like a great artwork, the parables particularly invite us into fresh perspectives, and encourage us to become artists of our own lives, sharing in God’s imagination and creativity…  What do sheep and shepherds mean to you? They are very much part of my story but I often struggle with them theologically in my context today. This photo is from Forest-in-Teesdale, near where I was born. Indeed, the farm in the centre is one I knew years ago, working with local farmers on pressing issues of rural stress and suicide, social and economic survival, and other faith and environmental issues. For sheep and good shepherding, literally and spiritually, is crucial to the Durham Dales. High on the roof of England, though we once had the greatest silver mine in the world, even subsistence mining of many important minerals is now near impossible. The great hunting lodges of bishops and kings have gone, disappearing with the remaining tree cover swept from the fells. Only occasional rich people’s grouse shooting really accompanies sheep today, together with the ambiguous harvest of tourists sampling one of England’s last wildernesses. Shepherds, particularly on the highest ground, therefore remain heroic figures to me: extraordinarily resilient, weathering so many vicissitudes; and, above all, deeply, intimately, connected to their/my land and its communities. No wonder Cuthbert, the greatest saint of the North, began life as a shepherd. Sheep, and good shepherding, are part of the lifeblood of my native people. What however of other peoples? In these lands now called Australia colonial society was notoriously built ‘on the sheep’s back’. Whilst that was lifeblood for some, for others it meant the blood of death and dispossession. For in the pioneering work of John Macarthur and others, the sheep was arguably a weapon of mass destruction, and shepherds key players in frontier warfare. So what kind of shepherd do we value today?...  Plautilla Nelli - The Last Supper (c 1550) Plautilla Nelli - The Last Supper (c 1550) In many ways I hope that when you picked up your liturgy sheet tonight and saw the Renaissance picture of the Last Supper you saw nothing unusual. It’s Maundy Thursday – of course we’ll have a picture of the Last Supper. Some of the art historians among you however will I think have recognised that this is no ordinary painting. This is in fact – as far as we know - the first Last Supper by a female artist – Plautilla Nelli, a contemporary of Michelangelo, Titian and Tintoretto and influenced of course by Leonardo da Vinci who died some five years before her birth in Florence... One of the puzzles Christians have sometimes set themselves is to work out what light is being referred to in the first few verses of the Bible. For, apart from modern light forms, we are so used to thinking of light from the sun and moon, which, in the Genesis account, are only created later. Various possibilities have therefore been suggested by the great theologians. Some (such as Ephrem of Syria) have thus suggested the light was a pillar of fire, or (like Basil of Caesarea) that the essence of the sun without its actual substance, or even that the light came for the angels (in the case of Augustine of Hippo). However, in so far as we might respond, I think I would go with the Orthodox Church’s understanding of ‘the uncreated light’ of God in Godself. For, when we come to the first chapter of Genesis. we are speaking here of divine mystery, depth, purpose and ultimate meaning, not literal or even limited symbolic explanation of Creation. Rather, like our second reading today (For Light by John O’Donohue), the nature of Genesis chapter 1 is poetic and prayerful, seeking to lead us into sacredness. For above all, such texts are designed to renew our sense of wonder and participation in divine creation and our role as priests of God’s Creation…

Today’s Gospel lectionary reading (Mark 4.20-34) invites us into Jesus’ way of communicating, which is not just about speech, even accompanied by silence and action. It is a way of being, a way of living: a way of living as parables, a way of being as artists…

by Jon Inkpin, for Pentecost 7A, Sunday 27 July 2014 (St.Luke, Toowoomba) There is a great little art exhibition at the moment: in the Crows Nest Art Gallery. If you haven’t seen it, I encourage you to do so before it ends (on 3 August). The exhibition is by two talented local young artists, one of whom is our own Katherine Appleby. Katherine’s subject for this exhibition centres on fairytales and she has created some wonderful works, not least a powerful piece called ‘Fear’. In this, we see what appears to be a young girl walking into the midst of a dark forest, where wolves and wolf-like heads, eyes and mouths glisten in the darkness. Even the trees are dark and bare, devoid of foliage, symbolising the darkness and threat of fear itself. Isn’t that a powerful picture of how fear can feel to us? Look again though, and perhaps you may see other things. What, for instance, is the really fearful thing in the painting? Is it the dark woods? Is it the closure of the path and of the light? Is it the wolves? Or is it the girl herself? Is she, so central to the picture, actually the true source and figure of fear? Why, for instance, is she walking into the forest, into the darkness away from the light? She stands very self-possessed. So is she afraid of the woods and the wolves? Or are they afraid of her? The painting you see, like any fine work of art, reveals more as we look at it. It asks us not one but many questions, some of them surprising. It is an invitation to mystery, rather than a mere description or proclamation of the straightforward. Indeed, if you look very closely at Katherine’s painting of ‘Fear’ you will see that the girl’s face is also partly an old and partly a young face. As such, it expresses the awesome ambiguity of life, truth and our human condition. Which way of looking, being and living will we choose? Religion at its best is in many ways akin to art at its best, especially in its capacity to invite us into the awesome ambiguities of life. It is an invitation to mystery, not a mere description or safeguard of the straightforward. It is a means, like great art, by which we can hold our fear and our suffering and not be overwhelmed. It is a path on which we can walk with courage, through the darkness around and within us, through the grace of God, into the light and love of God... |

Authors

sermons and reflections from Penny Jones & Josephine Inkpin, a same gender married Anglican clergy couple serving with the Uniting Church in Sydney Archives

June 2024

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed