Our lives and world are shaped by the stories we choose to tell, and how we tell them. That is one reason the study of history is so vital. For it makes a huge difference what we choose to include, remember, and carry forward in the story of ourselves we share. So what story about ourselves and our world do we want to tell, and to carry forward, on this 47th anniversary of the official founding of the Uniting Church in Australia? How does this reflect the vision of church as beloved community which we heard about in our readings (from Ephesians chapter 2.17-22 and John chapter 17.1-11)? And how, vitally, do we see this story developing in the future?

0 Comments

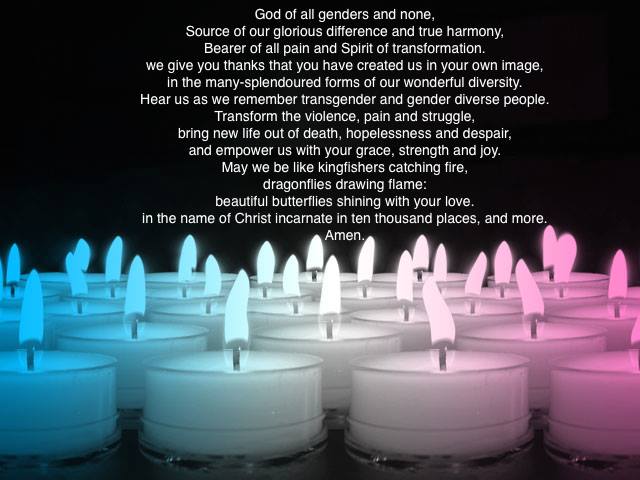

image: Brandy Martell, 400 block of 13th St near Frankland St, Oakland image: Brandy Martell, 400 block of 13th St near Frankland St, Oakland ‘Tell all the truth', wrote the poet Emily Dickenson, 'but tell it slant’. For ‘The Truth must dazzle gradually/Or every one be blind.’[1] That is pretty much Mark’s Gospel’s account of resurrection, isn’t it? Whilst other resurrection stories were attached later, the two earliest, and arguably the best, manuscripts of Mark’s Gospel stop abruptly at verse 8 of chapter 16, with women fleeing from an empty tomb and ‘saying nothing to anyone, for they were afraid.’ Furthermore, the text simply stops in mid-sentence, with the little preposition which means ‘for’. Mark’s Gospel, at least, is clear that resurrection is both truly astounding and impossible to convey straightforwardly. For how do we describe resurrection? How do we communicate resurrection? How do we live resurrection? The nature of resurrection is that it involves strange truths of transformation: which require, like so much great art, ‘telling it slant’; which rest on mystery; and which revolve around deep, lived, experience. For art, mystery, and experience: these three things are at the heart of the strange truths of resurrection we exult in today, as witnessed to by our readings and key images this morning, and the continuing life of you and I, and all who follow Christ…  Over the past few years at this service we have tried to focus on those who are presumed to have been present at the last supper of Jesus, but who are invisible in the written accounts – especially those who were not male or in any kind of authority. In a city like Sydney, where the presence of women and sexually and gender diverse people in church leadership is questioned in many quarters, it seems important on this night to say, ‘we were there too’. With this is mind, I looked for images of women at the Last Supper and came upon this one by Jamie Beck. I know too little about her, but Google suggests she is an American photographer and author of the 2022 book An American In Provence. She worked in New York for various prestigious fashion houses before moving to France. During COVID with her husband Kevin Burg she created a series called Isolation Creation sharing one photo per day of the lockdown experience, creating something beautiful positive each day. They were sold with proceeds going to the Foundation for Contemporary Arts COVID19 Emergency Grants Fund...  Un Mundo, by Ángeles Santo, Museo Reina Sofia Un Mundo, by Ángeles Santo, Museo Reina Sofia What value does the book of Revelation have for us, especially in the face of ecological crises? My guess is that most of us have not spent too much time on the Bible’s last book. Some people of course have, including those looking for a special secret code to life and history, and those puzzling out different timetables for Christ’s second coming. Such interpreters however typically have little concern for ecology, and some even welcome signs of environmental apocalypse. Faced by the strangeness of John the Divine’s visions, we may therefore be tempted to dispense with the book altogether. Yet that would be a mistake. For, as this morning’s reading (ch.12 vv. 1-9 & 13-17a) illustrates, truth and light can be received in the strangest places…  Plautilla Nelli - The Last Supper (c 1550) Plautilla Nelli - The Last Supper (c 1550) In many ways I hope that when you picked up your liturgy sheet tonight and saw the Renaissance picture of the Last Supper you saw nothing unusual. It’s Maundy Thursday – of course we’ll have a picture of the Last Supper. Some of the art historians among you however will I think have recognised that this is no ordinary painting. This is in fact – as far as we know - the first Last Supper by a female artist – Plautilla Nelli, a contemporary of Michelangelo, Titian and Tintoretto and influenced of course by Leonardo da Vinci who died some five years before her birth in Florence... How do you regard dragonflies? In the poem we heard earlier (As Kingfishers Catch Fire), the poet Gerard Manley Hopkins not only encourages us to be like them, but, in so doing, to be like Christ. Not everyone has always agreed however. In early colonial Australia for example, white fellas tried to kill dragonflies, just as they/we tried to kill so many other life-giving things that they/we did not understand. Those early colonialists saw dragonflies flying around and landing on their valuable horses, and they saw the horses moving and flicking their tails. So they thought the dragonflies were biting and making them crook. The colonialists were making things worse. The dragonflies were actually eating the mosquitoes and the gnats that were troubling the horses. They were life-givers, saviours even, not devils in disguise. In so many positive ways, dragonflies are thus evocative symbols for transgender people today. For, on this Transgender Day of Remembrance, we do well to attend to how bearers of light have been treated as embodiments of darkness. We do well, as our Gospel today (Luke 23.32-43) reminds us, to remember how Jesus was not crucified alone, and how others are also crucified today. And above all, we do well to affirm that it is only in recognising the light, in strange places, that we find salvation and hope for us all…

This is a well known but in some ways seriously annoying story, and I blame Luke – to say nothing of centuries of largely male, monastic interpretation - which can basically be summarised as ‘Hurrah Mary’ and ‘Boo Martha’. Or more aggressively as ‘stop complaining and pray harder’! Anyone out there feel like they’d like to muster at least a small cheer for Martha? Hurrah! This is a story that has been used as a means of social control in church and state, and a means of silencing the voices of women. For the very way this story is constructed, tends to make us choose sides. So, whether we are sympathising with Martha and feeling she’s a bit hard done by, or cheering Mary for breaking the gender stereotype, it is hard to remain neutral. The story itself sets up the two supposed sisters in opposition to one another...

Henri Nouwen, a Dutch Catholic priest, once said that “somewhere we know that without silence, words lose their meaning”. When there is silence, words also become infinitely more powerful. An enfleshed Word, like an infant Jesus – remembering that the word ‘infant’ comes from the Greek for ‘not speaking’ – carries most meaning of all; ‘the Word without a word’ as T.S Eliot expressed it in his poem Ash Wednesday...  Visitación, detail from mural at Casa Ave Maria in Managua, Nicaragua Visitación, detail from mural at Casa Ave Maria in Managua, Nicaragua How do you relate to Mary in our Christian tradition? Even mentioning her name opens up a host of feelings and thoughts for so many. As the Danish literary historian Pil Dahlerup rightly said, in an article entitled ‘Rejoice, Mary’: No woman and no deity in the Middle Ages attracted the poets like the Virgin Mary, mother of Christ. It is, however, hard to read what the poets write about Mary; we are inhibited by prejudices that block our understanding of what the texts are actually saying. Protestants dislike her because she is attributed divinity. Male chauvinists dislike her because she is a woman. Feminists dislike her because she is a woman in a way of which they disapprove. Nationalists dislike her because she represents an alien element in terms of creed and idiom. Marxists dislike her because they do not see her (in the North) as a figure of the people… Despite this, we cannot avoid Mary in Christian faith. Not least, although women and their lives and gifts are so few and highly gendered in the Bible, Mary simply cannot be erased. So what do we make of her today?...  We should have been listening to Jo talking about baptism today – but life in Sydney has been temporarily interrupted, so that will have to wait. Instead, we have a chance to look at this wonderful story of interruption and crossing over from Mark’s gospel (Mark 5:21-43). It is without doubt my own personal favourite gospel reading, so I offered to chat with you about it for a few minutes – and I hope over our Zoom coffee we may be able to chat some more... One of the reasons I love this story, is that it is so cleverly constructed – two stories that mirror each other, one within the other like a pair of Baboushka dolls. In different ways they are each about boundaries, edges, and transition zones – the kind of liminal spots where God has the most space to work. And this is signalled in the very first verse, “when Jesus had crossed again in the boat to the other side”. Bit of homework for the next two weeks at home – count the number of times in Mark’s gospel Jesus crosses over the Sea of Galilee – I can promise you it is quite a few! It reminds me of Elizabeth Gilbert’s well-known book and film “Eat, Pray Love” in which the central character develops a love of the Italian word “attraversiamo”, meaning ‘let us cross over’. ‘Attraversiamo' seems to be Jesus’s motto – and a good motto for others too. But I’m ahead of myself.

On this occasion Jesus crosses over from Gentile territory where he has healed the so-called Gerasene demoniac, back to a Jewish area – a risky choice, though at this stage the crowds are more of fan mob than a lynch mob. Here Jairus, the leader of the synagogue falls at Jesus’s feet, begging for the life of his daughter. Now this is a big deal. Jairus was important, honoured – and he crosses from that powerful place, demeaning himself at the dirty feet of a ragged itinerant and highly dodgy preacher. He crosses over from the centre to the edge. Why? because his daughter – according to Luke’s account his twelve-year-old daughter, on the border of childhood and womanhood – is in the border land between life and death. Are you noticing all the borders and edges? There are more to come. Jesus goes with Jairus – of course! If the leader needs you, you drop everything and go, right ?– especially if it’s a life and death issue? But then there’s an interruption. The crowd is pressing close – no social distancing here, no boundary! And suddenly Jesus stops. He starts talking about someone having touched him and looking all around the crowd. Can you imagine that? No wonder the disciples are so confused. The leader’s daughter is dying, and he is worried about someone in a crowd bumping up against him! But of course, there was no accidental bump here. The touch was deliberate. Across all the borders of exclusion, gender, isolation, the woman who has been bleeding for twelve years reached out to touch another edge – the hem of Jesus’ garment. And it was enough. Her touch was forbidden on so many levels. Because of her bleeding, the woman would have been excluded from society, from religious ceremony, from every aspect of daily life for twelve years – all the years Jairus’ daughter has been alive in fact. Stuck on the edge of menopause, just as the girl is stuck on the edge of puberty, she dares to cross over – to be out in public, to touch a man, or at least his clothing, to make a bid for her life. And Jesus asks for more. By stopping, by acknowledging what has happened, he invites her to come across the border, from the edge to the very centre – to come and speak her whole truth. But while all this is going on, while Jesus has been ‘wasting time’, Jairus’ daughter dies, and word comes from the household not to trouble Jesus further. And watch the movement here – Jesus brought the woman from the edge, right into the thick of the crowd. But when it comes to the little girl, he allows no one to accompany him except his closest disciples and the child’s parents. Just as the excluded person needs to be brought from the edge to the centre to find wholeness, so the child whose parent is the ‘big shot’ needs to be taken to a quiet edge, away from others, there to be taken by the hand and receive the simplest of words in Aramaic, ‘ Talitha cum’, ‘little girl, get up’. (I love those two words, along with the one other word in Aramaic in the gospels, spoken to the deaf man, ‘"ephphatha," as being perhaps some of the only words in Scripture we can reasonably assume that Jesus pronounced – praying with them has a special resonance for me). Taking the child by the hand was of course forbidden – to touch the dead made Jesus ritually unclean. Yet he crosses over the border to bring her back, to invite her to cross the threshold into womanhood. Two women – two stories of crossing over and restoration to life – mirror stories that take us from the edge to the centre and back again. Don’t worry too much about the miraculous. Just notice the edges, the borderlands, the crossings, the risks, that are part of every human story of identity and transformation. For this story is of course also our story. This is who we are and just as the woman and the girl in these nested stories are restored to their true and emerging identities, so this story invites us to live out our identity; to risk the crossings, to inhabit the borders where wholeness happens. And not just at the individual level. For Pitt St is a borderland community – and I don’t just mean that we come from many different LGAs! We could easily take attraversiamo as our motto, as we cross borders of geography, religious belief, ableism, gender, sexuality, race and all the rest on a daily basis. So have a little think about the borders you have crossed in life; about the borderlands you have chosen or been forced to inhabit; and about the healing that unexpectedly you have found there. And let’s chat about some of that and Pitt Street’s calling over our tea and coffee later – but for now, ‘let’s cross over’ as we move to our affirmation of faith. Amen. by Penny Jones, for Pitt Street Uniting Church, Sunday 27 June 2021 |

Authors

sermons and reflections from Penny Jones & Josephine Inkpin, a same gender married Anglican clergy couple serving with the Uniting Church in Sydney Archives

June 2024

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed