Our lives and world are shaped by the stories we choose to tell, and how we tell them. That is one reason the study of history is so vital. For it makes a huge difference what we choose to include, remember, and carry forward in the story of ourselves we share. So what story about ourselves and our world do we want to tell, and to carry forward, on this 47th anniversary of the official founding of the Uniting Church in Australia? How does this reflect the vision of church as beloved community which we heard about in our readings (from Ephesians chapter 2.17-22 and John chapter 17.1-11)? And how, vitally, do we see this story developing in the future?

0 Comments

Interwoven Story-telling by Grace Williams (Community & Cultural Resource Officer, Leprena – UAICC Tasmania) Interwoven Story-telling by Grace Williams (Community & Cultural Resource Officer, Leprena – UAICC Tasmania) Twenty years ago now, I was working with the First Nations arm of the National Council of Churches, and was involved in organising a series of events called ‘Hearts are Burning’, each designed to re-ignite positive Christian engagement with First Nations people, and, above all, to help First Nations’ Christian voices to be heard. For the gifts of First Nations’ Christians are vital to any healthy futures for faith in these lands now known as Australia. As one of our keynote speakers back then, the late Aboriginal Bishop Jim Leftwich, would repeatedly, and strikingly, affirm, ‘the mission field has become the mission force.’ In other words, it is those who first received the Gospel in colonial, even imperial, form, who are typically now best equipped to speak genuine ‘good news’ in these lands today. That is part of why we mark today in the Uniting Church as the Aboriginal “Day of Mourning”: both to recognise the continuing impact of past imperial and settler colonial violence and also, crucially, to hear the voice of the Spirit speaking again today through First Nations peoples. It is therefore a huge delight to have Aunty Ali Golding with us again this morning, and, in a few moments, I want to hand over to her to offer her own reflections. For I do not intend to say too much myself this morning, except to share, very briefly, three questions which arise for me from our Gospel, as we mark this Day of Mourning…  Alex may, or may not, remember the first time we met. It was at the start of a new year in which, finally, I was resolved to affirm my gender identity publicly. Dressed as a female, that Sunday I consequently chose MCC at Petersham as the safest space in Sydney to go to Church – Pitt Street Uniting Church would also have been fine but I already knew too many people there and that would have caused premature attention elsewhere. The MCC worship was uplifting and the community immensely welcoming. Over coffee, I then remember a gorgeous young man speaking beautifully and articulately, passionately and gently, about faith, life, and the possibilities of joy and community for us all, whoever we are. He opened us up to the experiences he was having in his studies in the USA, and some of the wonderful new life of progressive churches there. That young man was Alex, and, little did we know it, but our lives were to intersect frequently in the following years. Not least, after I came out publicly, MCC Brisbane was my second spiritual home, alongside the terrific Milton Anglican community. As Pastor there, Alex helped accompany me through that stage of life, enriching Penny and I, as well as so many others, with his gifts and love. Hopefully, we too offered some mutual support. Indeed, just as Penny and I were honoured to share in Alex’s ordination at MCC, and to walk with him through that time, so the last thing we experienced in Brisbane was a blessing from MCC for our journey into new ministry at Pitt Street Uniting Church, conducted by Alex. It has therefore been such a joy to be reunited with Alex here in Sydney, sharing not only times of struggle – such as the queerphobic attacks upon Pitt Street and the wider LGBTIQA+ community earlier this year, but new steps, such as that for which we gather today. All this too, is part of the shared inspiration which Penny and I, like Alex, draw from the extraordinary text of the book of Ruth which we have just heard…  image: Rod Long on Unsplash image: Rod Long on Unsplash Of all the critiques of the Ten Commandments I have encountered, it was that of a twelve old girl which was most powerful and poignant. This was many years ago, during a confirmation class I was running. We had looked at various aspects of Christian Faith and were exploring its living out. The Ten Commandments were an obvious element for reflection in this, especially as, like many English churches, they were displayed prominently, alongside the Apostles Creed, on either side of the altar (communion table) in our village church. Typically, they did not evoke much reaction from young people seeking to be confirmed: either because many of the components (such as ‘do not murder’) were fairly easily agreed, or, most often, because confirmands were shy about entering into religious debate with older people. There are ways of changing that, and perhaps today younger people may be more self-assertive, but in general my experience is that confirmation classes can sometimes be hard going for all concerned! Consider my surprise then, when this twelve year old girl, who, even in other contexts, hardly ever said a word in public, suddenly launched an outburst, full of both vehemence and reason. ‘This is shocking, and abusive’, she said, ‘how can this be in the Bible? I cannot accept it.’ Her protest was about a number of things but especially the fifth commandment: ‘honour your father and your mother’. ‘How on earth can I do that?’, she said, ‘when my father so mistreated my mother and left myself and my family when I was so tiny’…  image: Hagar and Ishmael by John Stayn image: Hagar and Ishmael by John Stayn As I have lived most of my church life primarily in Anglican and ecumenical settings, I have to admit to some bemusement about the annual marking of the Uniting Church’s founding. I guess it is partly the equivalent of the patronal festivals in other mainstream Churches. However these typically centre on a particular saint, or an aspect of faith (such as the Holy Trinity), after which a particular congregation is named, not a particular Christian denomination. Denominationalism is, after all, a modern idea, and would be a horror to our Uniting Church Reformation forebears. Jean Calvin, for example, sought to reform the one universal Church of God, not to create an alternative. The great Methodist pioneer John Wesley also formed a vital and innovative new movement but never sought to leave the Church of England. That is pertinent in marking this anniversary. For it directs us back to the Uniting Church’s crucial ecumenical and ‘open future’ charisms. These are clear in The Basis of Union, the key Uniting Church founding document. As a body, we are only one very small part of the universal Church through time and space. Therefore, rather than being yet one more denomination, we are called to help pioneer new paths of faith and relationships. Our calling is always to be a Uniting Church, holding our structures lightly and open to new ways of being followers of Jesus with others. So how what might today’s story about Hagar say to us in that? For it is certainly a powerful challenge... What’s in a name? - often, a huge amount. First Nations peoples are very clear about that and the intimate relationship between naming, language more widely, culture, identity and flourishing. Other oppressed peoples know this too. Hence the suppression or promotion of different languages is so vital an issue: just look, for example, at Wales, Catalonia, Belgium or Canada. It is not simply good manners to use the language people ask of us. It is because, unless we do so, we are disconnected from layers of meaning and identity, place and community, history and, indeed, geology. Take my surname: Inkpin. This has nothing to do with writing or being a scribe, or seamstress. It comes from two ancient British words: inga and pen. Inga, in modern English, means people. Pen means hill. This tells me, and others, that I come from the people of the hill, with all the deep layers of connection this entails: to particular soil and environment; to history and culture; to others, past, present and future. Indeed, even today, there are English villages, not surprisingly on hills, with the name Inkpen. For whilst much was swept away by the two great imperial invasions of my native land, there are still fragments of British indigeneity left, and one is my surname. It is a living reminder that there are other ways of being English, and British, than what is usually asserted: there are always were, and there always will be. For when we look more deeply, the living fragments of traditional cultures in every land call us both to recognition of pain and loss, and also to fresh pathways of justice. This is part of today’s Day of Mourning. We will not find peace unless we recognise what has happened in this land - and particularly in this city; unless we repent – and much more radically than we whitefellas have so far done; and unless, in Midnight Oil’s words earlier,[1] we ‘come on down’ to the makararrata place, ‘the campfire of humankind’, ‘the stomping ground.’…

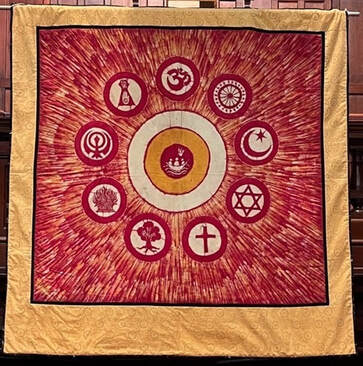

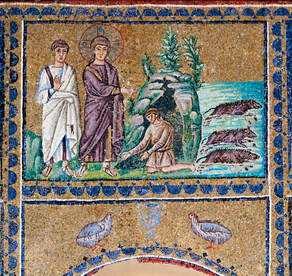

image: Stephen Leonardi on Unsplash image: Stephen Leonardi on Unsplash Our Gospel readings this week and next relate to what has traditionally been termed ‘the call’ of Jesus. Like the often very institutional church calls to ‘mission’, about which I spoke a fortnight ago, this call can often be interpreted quite narrowly, even oppressively. Indeed, it has sometimes been treated as a demand. Yet, in reality, as we see in both this week and next week’s Gospel’s reading, the call of Jesus is not so much a demand as an invitation. It seeks, as I said a fortnight ago, to draw us not drive us: to draw us into divine love and new life, not drive us into anything else, however admirable. For note well Jesus’ specific words in today’s reading from John’s Gospel: ‘come and see’. Like the words ‘follow me’ in Matthew’s Gospel next week, whilst Jesus invites, there is no compulsion. Nor is particular direction or content provided, although the Gospel record provides us early Christian understandings. Rather the invitation is primarily to an adventure of faith and experience. There is no requirement of belief as such, though that might emerge to give expression to the experience of the journey. There is no clear timetable, shape or schedule, or obvious destination. Jesus simply calls on those who will to set out on a shared pathway, walking together in trust. Is that how we see faith today?...  "What's in a name?”, said Juliet: “That which we call a rose. By any other name would smell as sweet.” Shakespeare’s famous lines speak of the power of names and designations. He presents Juliet, on her balcony, musing on the rose as a metaphor, in the context of her love for Romeo and the intense, age-old, conflict between two tribes - the Capulets (Juliet’s mob) and the Montagues (Romeo’s mob). Juliet proclaims that names have no ultimate meaning, other than those which people are willing to give them. As she puts it, in reference to Romeo: “Tis but thy name that is my enemy…. What’s Montague? It is nor hand, nor foot/ Nor arm, nor face. O be some other name/ Belonging to a man.” We do not, says Juliet here, have to be controlled by our names, by our tribes. We can choose how to live with them, and, in love, transcend them. Of course, Shakespeare’s story of the young lovers ends in tragedy. It is challenging to live with, and beyond, our names, our tribal identities. It can bring misunderstanding, opposition, and much worse. Yet is this not the path of true love, in the fullest dimensions of those words? Certainly, as we come today to bless our beautiful new interfaith banner, we do so in awareness of that same call to honour the different names of God, and not to let them control and divide us. For in the depth of all the world’s great wisdom traditions, true love, divine love, is not simply about reaffirming what is valuable in our tribal identities. True love is also about walking paths of inner and outer transformation together…  feature from Sant'Apollinare Nuovo, Ravenna feature from Sant'Apollinare Nuovo, Ravenna “Then the demons came out of the man and entered the swine, and the herd rushed down the steep bank into the lake and was drowned” – this gospel is not ‘good news’, if you’re a pig! Which leads us perhaps to ask in what ways is it ‘good news’? Is it simply bizarre? – the kind of tale that causes us to shrug our shoulders and try to forget about it? Or does it in fact have some things to offer us, latter day followers of Jesus, celebrating as we do today 45 years of that particular expression of Christian discipleship represented by the Uniting Church of Australia – a body of whose future existence no-one in this story – probably including Jesus, could ever have conceived...  ‘Cheer, cheer, the red and the white/ honour the name by day and by night’ – yes, that is the beginning of the song of the Sydney Swans. To my mind, and I admit my bias as a long-time Swans fan, it is the best of all the AFL club songs. For I won’t name names, but, with all respect, parts of some other clubs’ songs are, well, somewhat embarrassing. However, if Swans supporters are being completely honest, even we/they probably wouldn’t claim our anthem to be the greatest song ever written. I do wonder too, after all the rain we have had, and the consequent problems, whether the line ‘shake down the thunder from the sky’ is all that appropriate to sing right now?! I guess that is the point of what, in the best sense of the word, we might call ‘tribal’ songs. They may not always be perfect. They might even be awkward at times. We may not hold straightforwardly to all the details. We might even want to change some of them – and sometimes manage to make that change: just as the original Sydney Swans line ’while our loyal sons are marching’ was changed, in March last year, to ‘while our loyal swans are marching’, reflecting the emergence of the Swans girls youth program and the Swans women’s team (happily, albeit belatedly, to play in the AFLW later this year). They may also be quite annoying to others, even, after a victory, even a little insulting and enraging perhaps to some. However, despite all their limitations, such tribal songs are part of giving expression to shared experiences of deep connection and community, and to forms of faith and hope. As such, trite though they may be in comparison, I feel that they thus give us one way into approaching the historic ecumenical creeds of the Christian Church… |

Authors

sermons and reflections from Penny Jones & Josephine Inkpin, a same gender married Anglican clergy couple serving with the Uniting Church in Sydney Archives

June 2024

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed