Our lives and world are shaped by the stories we choose to tell, and how we tell them. That is one reason the study of history is so vital. For it makes a huge difference what we choose to include, remember, and carry forward in the story of ourselves we share. So what story about ourselves and our world do we want to tell, and to carry forward, on this 47th anniversary of the official founding of the Uniting Church in Australia? How does this reflect the vision of church as beloved community which we heard about in our readings (from Ephesians chapter 2.17-22 and John chapter 17.1-11)? And how, vitally, do we see this story developing in the future?

0 Comments

Interwoven Story-telling by Grace Williams (Community & Cultural Resource Officer, Leprena – UAICC Tasmania) Interwoven Story-telling by Grace Williams (Community & Cultural Resource Officer, Leprena – UAICC Tasmania) Twenty years ago now, I was working with the First Nations arm of the National Council of Churches, and was involved in organising a series of events called ‘Hearts are Burning’, each designed to re-ignite positive Christian engagement with First Nations people, and, above all, to help First Nations’ Christian voices to be heard. For the gifts of First Nations’ Christians are vital to any healthy futures for faith in these lands now known as Australia. As one of our keynote speakers back then, the late Aboriginal Bishop Jim Leftwich, would repeatedly, and strikingly, affirm, ‘the mission field has become the mission force.’ In other words, it is those who first received the Gospel in colonial, even imperial, form, who are typically now best equipped to speak genuine ‘good news’ in these lands today. That is part of why we mark today in the Uniting Church as the Aboriginal “Day of Mourning”: both to recognise the continuing impact of past imperial and settler colonial violence and also, crucially, to hear the voice of the Spirit speaking again today through First Nations peoples. It is therefore a huge delight to have Aunty Ali Golding with us again this morning, and, in a few moments, I want to hand over to her to offer her own reflections. For I do not intend to say too much myself this morning, except to share, very briefly, three questions which arise for me from our Gospel, as we mark this Day of Mourning…  Does doctrine divide? I sometimes hear that these days. Indeed, I have even heard people say they do not believe in doctrine at all. That, if you think about it, is quite a contradiction in terms. For anything you believe in, or do not believe in, is itself a doctrine. Doctrine, after all, really just means teaching. So, if someone says they do not believe in doctrine, are they really saying they do not want teaching in our world? Are all viewpoints, from flat earthers to conspiracy theorists, really equal? I suspect that what people really mean is that they do not believe in dogma: understood as authoritatively claimed beliefs which are essentially simply imposed, and resistant to questioning, reason and experience. Modern law and science are not, in that sense, dogma, but they are forms of doctrine: guidelines or teaching which enable us to live, and, hopefully, grow together. The same can be said of doctrines of faith. Like law and science, they can be used to divide. However, if they are open to development, they can be vital as a means to enable us to live, and grow. This is core to our Gospel passage this morning (from Matthew 16.13-20), which both contains powerful and particular expressions of faith in Christ and also an abiding invitational question; ‘but who do you say I am?’ It is, I believe, in that creative doctrinal tension, that Christians best live and thrive…  image: Hagar and Ishmael by John Stayn image: Hagar and Ishmael by John Stayn As I have lived most of my church life primarily in Anglican and ecumenical settings, I have to admit to some bemusement about the annual marking of the Uniting Church’s founding. I guess it is partly the equivalent of the patronal festivals in other mainstream Churches. However these typically centre on a particular saint, or an aspect of faith (such as the Holy Trinity), after which a particular congregation is named, not a particular Christian denomination. Denominationalism is, after all, a modern idea, and would be a horror to our Uniting Church Reformation forebears. Jean Calvin, for example, sought to reform the one universal Church of God, not to create an alternative. The great Methodist pioneer John Wesley also formed a vital and innovative new movement but never sought to leave the Church of England. That is pertinent in marking this anniversary. For it directs us back to the Uniting Church’s crucial ecumenical and ‘open future’ charisms. These are clear in The Basis of Union, the key Uniting Church founding document. As a body, we are only one very small part of the universal Church through time and space. Therefore, rather than being yet one more denomination, we are called to help pioneer new paths of faith and relationships. Our calling is always to be a Uniting Church, holding our structures lightly and open to new ways of being followers of Jesus with others. So how what might today’s story about Hagar say to us in that? For it is certainly a powerful challenge...  My wife Penny and I met at theological college. It was certainly not love at first sight. I was quite introverted, not trying to give away much of who I was, and Penny – well, Penny was very nervous and came across as a terrible caricature of an English middle-class blue stocking type of woman: think, those of you who can remember back that far, of Joyce Grenfell in the old St Trinian’s films. Our college was overwhelmingly full of men, with this being only the second year a handful of women had been admitted. So, when I met Penny in the first hour or so after arriving, I thought: ‘well, if this is how the women are here, I am simply not going to survive!’ I guess that was one factor in our initial relationship: sheer survival in an age and culture still trying to come to terms with the equality of women as a whole, never mind wider gender diversity. It was an earlier reminder that, if Penny and I were to minister, it would be as salt. We would be adding fresh flavour to both the Church and the wider world, seeking to provide healing or simply preservation for some of us, and, from time to time, perhaps irritating others into whose wounds we might be placed to aid healing. Maybe some will have views on how well, or otherwise, we have done that so far. Our hope and prayer is, in the words of Jesus in our Gospel reading today, that we, with others, will never lose out saltiness… What’s in a name? - often, a huge amount. First Nations peoples are very clear about that and the intimate relationship between naming, language more widely, culture, identity and flourishing. Other oppressed peoples know this too. Hence the suppression or promotion of different languages is so vital an issue: just look, for example, at Wales, Catalonia, Belgium or Canada. It is not simply good manners to use the language people ask of us. It is because, unless we do so, we are disconnected from layers of meaning and identity, place and community, history and, indeed, geology. Take my surname: Inkpin. This has nothing to do with writing or being a scribe, or seamstress. It comes from two ancient British words: inga and pen. Inga, in modern English, means people. Pen means hill. This tells me, and others, that I come from the people of the hill, with all the deep layers of connection this entails: to particular soil and environment; to history and culture; to others, past, present and future. Indeed, even today, there are English villages, not surprisingly on hills, with the name Inkpen. For whilst much was swept away by the two great imperial invasions of my native land, there are still fragments of British indigeneity left, and one is my surname. It is a living reminder that there are other ways of being English, and British, than what is usually asserted: there are always were, and there always will be. For when we look more deeply, the living fragments of traditional cultures in every land call us both to recognition of pain and loss, and also to fresh pathways of justice. This is part of today’s Day of Mourning. We will not find peace unless we recognise what has happened in this land - and particularly in this city; unless we repent – and much more radically than we whitefellas have so far done; and unless, in Midnight Oil’s words earlier,[1] we ‘come on down’ to the makararrata place, ‘the campfire of humankind’, ‘the stomping ground.’…

If I was to ask any group of Christians what titles for Jesus they knew and used most, what do you think they/we would come up with? Lord and Christ would probably be the first titles in the list, followed by others such as Saviour, Shepherd, Brother, Friend, Son of God, Son of Man and so on. The Way, the Truth and the Life, together with the Bread of Life, would also be likely to get an early look in. What about Gate, or the Gate, though? I reckon that would pretty low down the list, don’t you? Yet, Gate is a very important title for Jesus, and, arguably, a key title often honoured very much in the breach down the Christian centuries. For, let’s face it, Christians have spent an inordinate amount of time using Jesus as a means, a gate, to exclude and keep people out, or to stop one another going out, and, in the words of Jesus in our Gospel reading tonight, finding good pasture. We don’t even have to be members of the LGBTIQA+ community to know that such gatekeeping is so very much still alive and with us in both our world and its Churches. This is such a great shame, not simply because of the harm caused, but because, as John’s Jesus proclaims, the Gate of Christ is precisely created to open up our lives and world to deeper meaning and more loving relationships. One of the vital gifts of Queer theology and Queer Church spaces is therefore to share Jesus as the Gate to life in all its fullness, and for the followers of Jesus to become ever more alive signs of that holy abundance. That, at least, is at the heart of my reflections on this wonderful bible passage (John chapter 10, verses 7-10) which we just heard…  photo: by Ashin K Surash on Unsplash photo: by Ashin K Surash on Unsplash Today’s reading from Luke begins with the often-repeated phrase ‘don’t be afraid’. It is a phrase so often repeated that it has given me pause for thought this week. Do the Scriptures encourage us all the time not to be afraid, precisely because the people for whom they were written were in fact constantly afraid? They would have had good reason to be. As far as we can tell most early followers of Jesus were subject peoples living in occupied territory. The might of Rome was a constant threat, taxes were high, financial insecurity inevitable, and it was not as though they had the securities of modern medicine, analgesics, and antibiotics. Moreover, the expectation of Christ’s imminent return, coupled with an increasing impatience at its delay sounds an anxious apocalyptic note throughout the pages of the New Testament. But what about ourselves? Are we also afraid? Religion has after all for centuries traded in fear – fear of God’s punishment and condemnation, sweetened by the promise of salvation for those who truly believe, (some have called that ‘pie in the sky when you die’); treasures in heaven beyond the reach of moth, rust, and thieves – and after the last few months in Sydney I’d want to add mould! So, are we also afraid? This is an important question as we enter a period of considering our mission as a congregation. If we are afraid, what are we afraid of? – remembering that fear is not all bad. It is a great motivator to action. But the encouragement of the gospel is not to be afraid, but to act from a different place – a place where we don’t have supposed ‘treasures’ to defend; a place where we are set free from the need to control and secure; a place indeed as the letter to the Hebrews calls it, of faith... This is a well known but in some ways seriously annoying story, and I blame Luke – to say nothing of centuries of largely male, monastic interpretation - which can basically be summarised as ‘Hurrah Mary’ and ‘Boo Martha’. Or more aggressively as ‘stop complaining and pray harder’! Anyone out there feel like they’d like to muster at least a small cheer for Martha? Hurrah! This is a story that has been used as a means of social control in church and state, and a means of silencing the voices of women. For the very way this story is constructed, tends to make us choose sides. So, whether we are sympathising with Martha and feeling she’s a bit hard done by, or cheering Mary for breaking the gender stereotype, it is hard to remain neutral. The story itself sets up the two supposed sisters in opposition to one another...

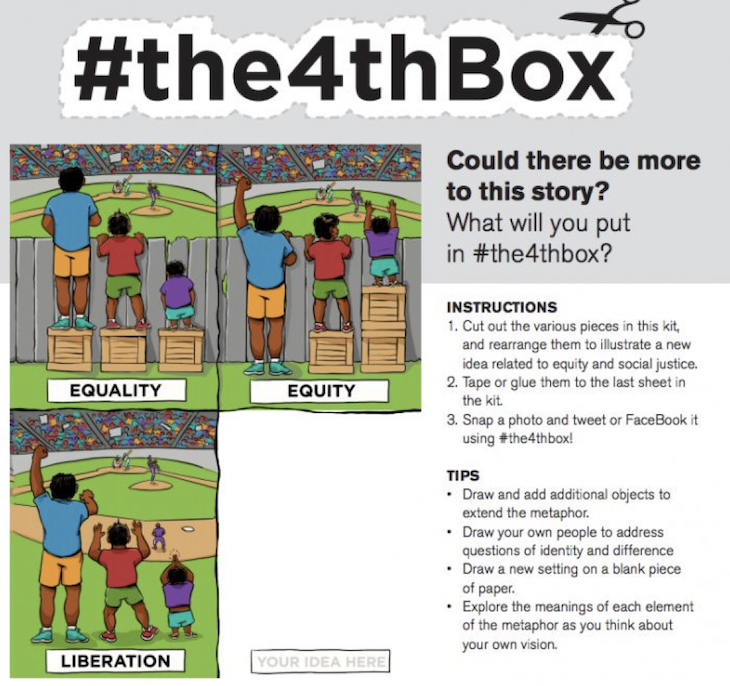

In recent years some of my Aboriginal friends have said to me that they do not really believe in the Australian concept of Reconciliation and some of the activities, like Reconciliation Action Plans, which have accompanied it. Meanwhile some Church leaders have said to me that they do not see much point in engaging actively in ecumenical endeavours. So why, we might ask, are we marking the Week of Prayer for Reconciliation and the Week of Prayer for Christian Unity this morning? Actually I did wonder about changing the title on the front of our liturgy sheet today to ‘Prayer for Just Relationships and Communion in Christian Diversity’. That, for me, would be at least part acknowledgment of the difficulties of the words Reconciliation and Christian Unity and the need for re-imagining as well as building on the good work of the past. However I have left Reconciliation and Christian Unity in the title for the present, so we honour where we have traveled. Nonetheless, as we hear our two readings this morning (from Revelation chapter 22 and John chapter 17), we do well to reflect more deeply on the words and constructions we may use in order that we share in more fruitful pathways for our work together with others. For that purpose I also offer you the cartoon meme entitled the #4thBox, as an encouragement to deeper prayer, more imaginative reflection and more creative action…

|

Authors

sermons and reflections from Penny Jones & Josephine Inkpin, a same gender married Anglican clergy couple serving with the Uniting Church in Sydney Archives

June 2024

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed