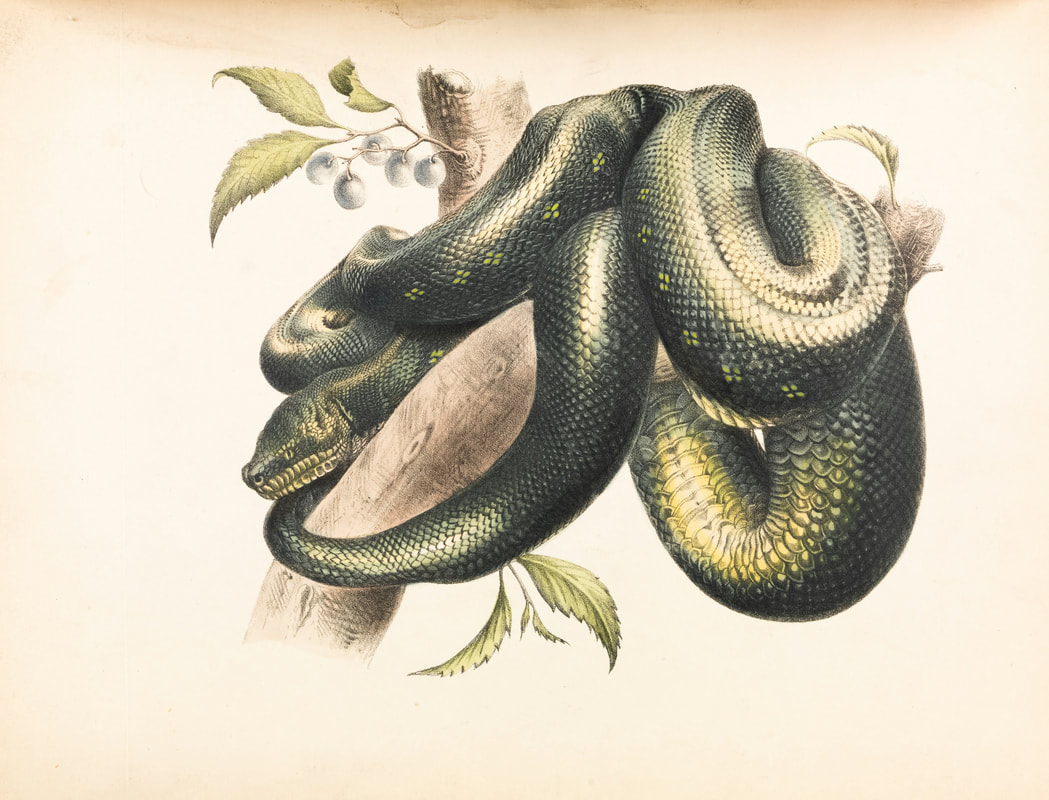

image from Museums Victoria on Unsplash

image from Museums Victoria on Unsplash At once, we may find, at least parts of, ourselves recoiling. Such ancient Judaeo-Christian symbols, and language of sin and salvation, are not always easy to handle, or even name, in our modern world. In more liberal parts of the Western world, we are also encouraged to emphasise affirmation, education, and progress. Today’s readings can thus come across at first hearing as harsh and disturbing, with alien and, apparently, archaic elements. Indeed, words such as judgement and condemnation are also prominent, often sitting ill at ease with contemporary campaigns for pluralism and inclusion. Yet can we, as followers of Christ, really avoid them? If we do so, are we not left with a watered down and biblically unrecognisable form of Christian Faith? As the 20th century theologian H. Richard Niebuhr alleged of the liberal Protestantism of his day, do we end up with:

A God without wrath (who) brought man without sin into a kingdom without judgment through the ministrations of a Christ without a cross.

Niebuhr may have partly caricatured liberal and progressive theological tendencies. Yet his critique is important if we seek to engage with the discomfort of scripture passages such as those we heard today. If we are to grow in faith, and offer distinctive Christian gifts to the wider world, then we simply cannot dodge the challenges of what these readings, and our wider traditions, call sin, judgement, and the cross. Let me therefore explore these key elements of what the Christian Faith calls ‘salvation’, before returning to the significance of seeing Christ as a snake…

understanding sin

Firstly, how do we understand sin? Now, I know some Christians are obsessed with the word ‘sin’, and with applying it to certain kinds of, largely personal, behaviours with an ungracious spirit. In response, there is a tendency among progressive Christians to avoid the term: instead emphasising social justice and human potential for good. Neither approach however really works for me, and not only because there is a balance to be struck between the deficiencies and strengths of human nature, and because personal and social transformation are not two different things. No, my principal concern is theological. I do not believe that Christian Faith is essentially about ethics, or psychology, or social or political change. Of course, it is closely bound up in its expression with each of these aspects of life, and more. However, where it starts to be reduced to any of those things, by conservatives or progressives, then we have lost our way. For ultimately, if Christian Faith has any meaning, it is about God, and how we engage with God.

Focusing on God: this is the central point of our readings today, and, indeed, at their best, of all scripture passages. What, and where, are we looking at when we seek healing and salvation? Are we looking at one another, and our human constructions, or is there something more? Linguistically speaking, as some scholars tell us, the word ‘sin’ means ‘missing the mark’. It is like an archer shooting at a target and not succeeding, because their focus is wonky or obscured. This is key to understanding the story of the bronze serpent in the book of Numbers. For the core issue here is that the ancient Israelites were missing the mark. They were not being the people they were called to be: the people of faith and hope and love in the covenant relationship they had with God. They had lost faith and hope in God. They felt pain and depression in the wilderness. Their focus was on themselves and their troubles: just like people of Jesus’ day; just like people in our day; just like, let’s be honest, you and I, more often than we would care to admit. The point of the bronze serpent on the pole, like the cross of Jesus for John’s Gospel, is that it helps restore true focus and living relationship with the source and ultimate strength of liberation and love.

understanding judgement

For, secondly, understanding sin, in relationship to loss of focus, missing the mark, is where judgement comes in. Human beings are inclined to think of judgement in judicial terms, as if God were a police officer, a judge in a courtroom, or a prison guard. That is the way Martin Luther, for example, originally saw God. Luther despaired of the impossibility of living by divine righteousness, because he thought of this as legal, or forensic: something to achieve, which human beings patently could not. He therefore felt the burden, the heaviness, the effects of feeling judged by such standards. Only when he saw that God had already set us free in Jesus, whatever we have done or struggle to do, could he experience the divine freedom of inexhaustible, eternal, love. Theologically speaking, spiritual experiences of judgement and condemnation are consequently fundamentally about whether we live, or otherwise, in life-giving relationship, rather than about keeping any supposed set of rules: that is, to use the classic formulation, they are about grace not law. One of the key problems with today's Gospel passage thus comes when a scriptural phrase becomes an idol, like that about 'believing in the name of the only Son of God'. Out of a particular context, this describes one of the ways in which life is fruitful when we recognise what Christ points us to and enables us to experience. However it does not need to be used as a false assertion of a supposed need to sign up to a narrow tribal understanding of just a set of people who call themselves Christians. God's love, as represented by the second Person of the Trinity, is far, far, more expansive than that.

People in the ancient world also did not apply to events some of our modern cause and effect frameworks. Consequently, occurrences we would first identify in scientific or socio-political terms would be directly attributed to the hand or will of God. Hence events such as biblical plagues, or the poisonous serpents of the book of Numbers, were recorded as the judgement of God. We would put things differently but they witness to similar experiences we encounter today, whether in environmental, or socio-political, challenges. We might not, for example, attribute the ramifications of climate change directly to divine action. Yet they witness to a similar lack of focus on those things which really matter: namely loving, just, and sustainable, relationships with others, the wider creation, and the source of all being. The feelings which thus arise from the ravages of climate change do indeed often feel like a kind of judgement, and even condemnation, of the betrayal of covenantal relationship. Similarly, in John’s Gospel, it is not that God is directly condemning us, as, or when, we miss the mark and fail to walk in pathways of light. Rather, like Nicodemus, whose encounter with Jesus directly precedes today’s Gospel passage, we ourselves bring on experiences that feel like judgement when we remain in dark places.

understanding the cross

This brings us, thirdly, to the cross: and to the bronze serpent, as a similar, and preceding, symbol of divine salvation. For. as John’s Gospel proclaims, God intends that all of creation should live in light and not darkness – and, note well, this is all of creation in the text, not simply humanity, or a part of it. As this scripture affirms, God does not therefore condemn us when we sin: when we lose our focus; when we experience alienation which feels like judgement. Instead, this is the opportunity for a fresh start. For, if sin, missing the mark, alienation of various kinds, is pervasive in human experience, this is not our ultimate meaning. Rather, as the 19th century English theologian F.D.Maurice put it, even in the face of seemingly intractable problems, we need to remember that neither sin, nor the Fall, are the centre of Christian theology. The core of Christian Faith is always the God of grace. Mercy is what unites us in God, not the anger, or judgement, or hate, which arise from the fears and false passions of human beings.

Again, we are challenged to reflect on what is our true focus. The ancient Israelites took their eyes off the God of mercy and liberation who had led them out of oppression. Yet, amid the consequences, God offered a way back, in the form of the bronze serpent on the pole. It was an image of the destruction they had helped bring upon themselves, and yet, at the same time - precisely in being a reminder of their pain and alienation – it was a pathway to healing and new life. Like the cross, a similar symbol of both pain and destruction and of mercy, the bronze serpent offered hope out of recognition of their weakness and their need for God’s grace.

atonement as snake healing

In both our readings today we are consequently offered stories and symbols which speak of how salvation through atonement works – how being made one with God works. In both cases, we are shown that we have to recognise the consequences of our sins, our lack of focus, our missing of the mark. In both cases, we have to look on what represents pain: so that, out of our weakness, not our supposed human strength, we are transformed by grace. It is like God is offering us a vaccine for the violence of our lives and world. It may help to think about how we handle the threat of dangerous snakes today. Snake venom is indeed deadly, yet we ‘milk’ venomous snakes for medicinal purposes: to provide antidotes from bites, to prevent blood from clotting, to treat pain, deal with diabetes, address cancer.

This is why John’s Gospel encourages us to see the cross as a symbol of salvation. For, in this Gospel, it is not so much in the resurrection but when Jesus is lifted high on the cross that God’s work in them is fulfilled. For John’s Gospel is clear that, like the bronze serpent for the ancient Israelites, the crucifixion brings health and renewal. It is not a device of God’s punishment. Rather Christ takes the punishment of human authorities and transforms it. Perhaps, as one of our recent visitors, Father James Alison, puts it, from a Girardian perspective, we see in this how God’s grace transforms human violence: the mimetic violence that we continue to inflict upon one another and the wider creation. Instead, Christ on the cross transforms this violence that clings to us and which we feel as judgement. Whereas the snake was a figure of the Fall of humanity, Jesus the snake offers us a new creation. Just as the serpents in the wilderness were disarmed and wholeness restored to the people of Israel by Moses’ action, so God in Christ on the cross disarms all the powers of sin and evil, and offers us renewed wholeness of being. The victory is complete. Healing is offered to us if we would focus upon it. So will we take it? In the grace and mercy of God, Amen.

by Josephine Inkpin, for Pitt Street Uniting Church, 4th Sunday in Lent, 10 March 2024

RSS Feed

RSS Feed