image: Brandy Martell, 400 block of 13th St near Frankland St, Oakland

image: Brandy Martell, 400 block of 13th St near Frankland St, Oakland

image: Brandy Martell, 400 block of 13th St near Frankland St, Oakland image: Brandy Martell, 400 block of 13th St near Frankland St, Oakland ‘Tell all the truth', wrote the poet Emily Dickenson, 'but tell it slant’. For ‘The Truth must dazzle gradually/Or every one be blind.’[1] That is pretty much Mark’s Gospel’s account of resurrection, isn’t it? Whilst other resurrection stories were attached later, the two earliest, and arguably the best, manuscripts of Mark’s Gospel stop abruptly at verse 8 of chapter 16, with women fleeing from an empty tomb and ‘saying nothing to anyone, for they were afraid.’ Furthermore, the text simply stops in mid-sentence, with the little preposition which means ‘for’. Mark’s Gospel, at least, is clear that resurrection is both truly astounding and impossible to convey straightforwardly. For how do we describe resurrection? How do we communicate resurrection? How do we live resurrection? The nature of resurrection is that it involves strange truths of transformation: which require, like so much great art, ‘telling it slant’; which rest on mystery; and which revolve around deep, lived, experience. For art, mystery, and experience: these three things are at the heart of the strange truths of resurrection we exult in today, as witnessed to by our readings and key images this morning, and the continuing life of you and I, and all who follow Christ…

2 Comments

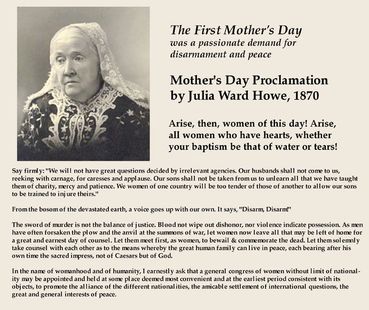

Enthroned Virgin and Child (1150-1200 France) & Bodhisattva Avalokiteshvara in Water Moon Form/Shuivue Guanyin (907-1125 Liao dynasty) from the Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York Enthroned Virgin and Child (1150-1200 France) & Bodhisattva Avalokiteshvara in Water Moon Form/Shuivue Guanyin (907-1125 Liao dynasty) from the Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York Wake up! Keep awake! These are familiar injunctions in Advent. What however do they mean to us today? What are we to wake up to? And for what is it that we are to keep awake? At the heart of the Advent and Christmas mysteries, is a call to transformation: an invitation to awaken, to recognise what is really going on in ourselves and in the wider world; an invitation to respond, to wake up, to the divine possibilities latent, or birthing, within us. Whether it be through stories and images of wonder and imagination, as in the Christmas angels and the Magi, or in today’s Gospel challenge to see beneath the changes and chances of our immediate existence, we are invited into transformation: the ever-transforming power of divine love and awakening…  The clergy of the Uniting Church of Australia are obliged to agree that they will baptise new members in ‘the name of the Father and of the Son and of the Holy Spirit’. It is one of really only a handful of non-negotiables. So, why? What does this mean? And what matters about this particular attempt at describing God?...  So, angels are coming. How will we greet them? At once, perhaps we start to ponder: but what are we greeting? And are there such things as angels anyway? Modernity’s functional materialism has so much to answer for! From a Reformed Christian perspective today it is also sometimes hard to engage. For whilst the classic Reformed theologians were quite clear that angels are to be taken very seriously, as they appear in so many places in the Bible. Yet later thinkers have found less value. In some quarters of liberal and progressive Protestantism they almost became erased: rejected with supposedly passé doctrines like the virgin birth, miracles and even major articles of the historic creeds. Ironically, as liberal Protestantism declined, other faith constructions began to thrive, not least New Age spiritualities with their extraordinary mix of angelic and other speculations. Did demythologising thereby open the door to old heresies? - as well as to a loss of divine wonder in the secular world? Certainly, as Les Murray pondered in his poem ‘The Barranong Angel Case’, which we heard read earlier, do we have the capacity to see and receive the angels of Christian tradition today?  Jesus and the Bent Over Woman, by Sister Barbara Schwarz, www.artafiregallery.homestead.com Jesus and the Bent Over Woman, by Sister Barbara Schwarz, www.artafiregallery.homestead.com Today’s Gospel story is one which resonates powerfully with me. For I had lower back problems for many years, and I still vividly remember my back going into total spasm as I once tried to change trains at Strathfield station. I was bent double and simply could not move, despite the help of others. It was a key moment in which I began to realise that my life, and especially my relationship to my body, had to change. I had to start listening to my body, in which so many emotions, not least denied gender and sexual emotions, were trapped. Not simply physically, but in other ways, I had to learn to bend and unbend, more fully to know and flow into my life and spirit. Now, of course, not all our ailments and physical challenges have obvious spiritual connections. However many, in my experience, do, and this is certainly part of what the Gospel writer is trying to say to us in our story today. For whilst we may speculate on the likely form of physical arthritis with which the woman may have been afflicted, Luke is calling us to recognise our spiritual arthritis and its potential for transformation in God. At this time, in the life of this community, and the wider Church and world, it is perhaps well worth reflecting upon. Indeed, as we continue to ponder our own mission calling together, it is good to ask what bending and unbending might represent for us, not least in our prayer and worship life. For whilst it might be tempting to consider today’s Gospel story in relation to many whose physical bodies and lives need unbending, I believe that the great mystic Evelyn Underhill had it right when she said: We mostly spend our lives conjugating three verbs: to Want, to Have, and to Do… forgetting that none of these verbs have any ultimate significance, except so far as they are transcended by, and included in, the fundamental verb, to Be. Prayer and worship, she, and I, would propose, are about helping us with that fundamental verb: bending and unbending our lives and bodies, our whole selves, be-ing, in relationship to the Spirit of all…  When my wife was ordained deacon in the Anglican Church, she was heavily pregnant with our twin daughters. ‘I am a holy trinity’, she famously declared in a subsequent homily. Of course, this was partly a joke, not a serious attempt to restate classic doctrine. Yet she was making vital points about the need to locate the great ecumenical doctrine of the Holy Trinity in life and experience, as well as in prayerful and intellectual rigour. We would certainly not want to over-exalt a female pregnant trinity, especially when its members are manifestly not equal or in reciprocity. However my wife had a case, I think, in drawing attention to deep aspects of mutuality, indwelling, and love. Not least she was highlighting how God as Holy Trinity is profoundly relational and embodied. For, whilst God in essence is transcendent, God’s energies are found dynamically in all aspects of our lives and world. In this sense. God in Holy Trinity is not only found in our variegated gendered experiences. God in Holy Trinity is always pregnant with possibilities of which we can but yet hardly dream. As Matthew 28.16-20 highlights, this is not only a declaration of profound loving mutuality. It is also an invitation to travel on to further transformation in the presence of a mystery which calls us into deeper being and becoming...  a shared reflection and invitation by Josephine Inkpin (J) & Penny Jones (P)... (P) We‘ve just heard two different accounts of Jesus’ resurrection, haven’t we?! (Mark 16.1-8 and John 20.1-18) So what we do make of that – and all the other resurrection accounts which cannot be simply conflated? More importantly, what does Resurrection mean to us – to you, to me, to all of us together? That is not a question which can be answered in a few minutes of Reflection. Jo and I have therefore decided to open up a dialogue, which we hope will encourage us all to share in the days ahead. For one thing which is absolutely clear about Jesus’ resurrection of is that it is related through a multiplicity of stories and symbols. These come from different people and biblical outlooks and they thereby also invite us to share our own experiences and insights into Resurrection. For Resurrection is an extraordinary reality we celebrate today. Yet it is not a simple ‘fact’, is it Jo? Isn’t it rather an invitation to see, and travel into, deeper experience, deeper love, and deeper mystery?…  Today is Trinity Sunday, when the church tries to describe the indescribable; to point to the character and action of the Divine that is always dynamic and evolving. The early teachers of the church came to describe God as Trinity – three equal ‘persons’ or expressions of God, Father, Son and Spirit – or in the beautiful and more inclusive language of Julian of Norwich, the Maker, the Lover and the Keeper. It is a picture of God as a community of equality. That in itself is of immense importance in a world where inequality and autocracy tend to rise up as we have seen this week in the United States. The picture of God as Trinity shows us how God’s very being and nature is about relationship and love. How might this picture of God as Trinity help us in these days of change and challenge across our world?...  One of the wonderful things about many Jewish people I have met is their capacity to wrestle with our human experience and ideas of God. They just do not settle for simplistic answers, especially when it is comes to the really big human questions of hope and suffering, life and death. Indeed there is a famous saying: ‘ask two Jews, get three opinions.’ Now, of course, this, can occasionally lead to a certain stubbornness and unnecessary conflict. It points us however to the very heart of biblical religion, especially as we find it in the Hebrew Scriptures. For the God of the biblical tradition is very much a God with whom to wrestle. We see this, not least, in the book of Hosea, from which we hear again today. Indeed, the God whom Hosea reveals is very much a God wrestling with God’s own compassion, very much as a parent wrestles with their own hurts and hopes for their child. This is the deepest, most mysterious, heart of love, and it is into this kind of love we baptise Margaret Rose today…  Mothers Day – what do we make of it? In some ways is a strange, and very modern, development. Indeed, if we ever needed an example of how culture shapes an idea in different ways, then Mothers Day is it. Originally it was a revolutionary rallying call to mothers to take action to save their children and stop war. Yet today it is a much tamer and commercialised affair: a largely domesticated call to do something for mothers, however small. Instead of mothers themselves organising campaigns for peace and justice, as they did when it began, Mothers Day today is mainly an opportunity for mothers to be pampered by their nearest and dearest, at least for one day. So where does God’s love fit in all of that? Is there anything Christian faith might have to say to affirm, deepen, and expand our meaning of Mothers Day? Well, yes: especially on this particular Mothers Day, which is also the feast day of the medieval saint Mother Julian of Norwich, and the first day of this year’s Week of Prayer for Christian Unity. Both of those events help us see and use Mothers Day more fully, as an opportunity to share the mothering love of God more abundantly: not only by rightly valuing that love in our own mothers, but by renewing that love in our own selves, and by extending that love to others, different to us and further afield… |

Authors

sermons and reflections from Penny Jones & Josephine Inkpin, a same gender married Anglican clergy couple serving with the Uniting Church in Sydney Archives

June 2024

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed