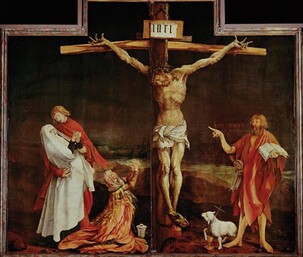

This painting has been deeply influential for later artists’ portrayals of the cross, including three of those to follow this morning. It illustrates a significant late medieval shift towards exploring Christ’s humanity. Alas, this was somewhat lost at the Reformation, both in its Catholic and especially its Protestant forms. Indeed, in many churches today, we tend to see only the bare cross. Even in Catholic churches, the cross can thereby become a mere symbol, pointing in an abstract manner to God’s metaphysical work. This image however is grounded in its context and the existential challenges of the Monastery of St Anthony, which was noted for the care of plague sufferers and skin diseases. Thus we see human anguish and the crucified Christ pitted with plague-like sores, showing that Christ fully shares in such afflictions. Not for nothing did the great 20th century theologian Karl Barth keep a reproduction of the Crucifixion in his study to remind himself that his role was to point to Christ crucified...

‘What is truth?’: Pilate’s words in our first reading today echo down the centuries. Artist have always been involved in exploring that question. Although Pablo Picasso, for example, was an atheist, his work employed many spiritual themes[1] and this work reflects a life-long wrestling with the Crucifixion, which also resonates in his great mural Guernica, in which Picasso similarly conveyed universal suffering through a single horse’s head. For, as insightful critics have observed,[2] Picasso in his best works was searching to express the presence of transcendence in the here and now, seeking (as Charles Pickstone put it) ‘some other realm of feeling and thought’ to handle suffering. Here Picasso helps us wrestle with what truthful meaning we can find in life with so much death afflicting us. Three experiences are particularly reflected in Picasso’s Crucifixion: firstly, the death, which he carried with him throughout his life, of his younger sister Conchita from diptheria, when he was 14; secondly, his close contact with war and its destructions, not least the effects of defeat, including the plight of refugees; and, thirdly, especially, the suicide of his friend Carlos Casamegas in 1901. What suffering, I wonder, do ourselves bring to this time?...

Picasso’s Crucifixion vividly portrays the raw anguish and desperation of human emotion arising from our intense experiences of death. Drawing on ancient Spanish faith and culture, our attention is shifted from the Christ figure to wider human agony, with crucifixions of all kinds named as both violent, unspeakable crimes and yet also places for the renewal of life. The sharp black and white of the crucified figure is thus set amid the colours of life. Picasso’s use of other images, including those of the bullfight, as in the transposition of the centurion and his spear, also encourage us to reflect upon how our own cultures both inflict, and also have the potential, to transform pain. Indeed, Picasso’s Crucifixion figuratively links the passion of Christ to other spiritual pathways which wrestle with the question of truth and the mystery of life in death. Note the figure of Christ with paddle like hands, very similar to Cycladic and North African divine imagery, as well as surrealism. To the left and right of Christ are figures which probably represent the moon, the sun, and possibly the virgin Mary. Art historians also suggest that the figure to the right is likely a reference to cultic Mithraic imagery. On the far left and right are the small Tau crosses of the two thieves. In the right foreground are the soldiers gambling for Christ’s garment. In the left foreground are two crumpled figures who both picture the two thieves and the revivification of Adam and Eve at the foot of the cross: the giving of new life even in the midst of death.

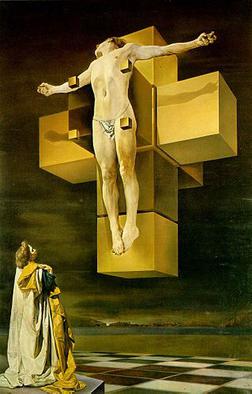

Our second reading today (John 19.1-16) challenges us to reflect on what provides true power and order for our lives and world. The narrative relates how the Romans ridiculed both Jesus and the Judaean people, whose land, faith and culture were under existential threat. Where is hope to be found in the face of such destructive forces? Dalí’s Crucifixion (Corpus Hybercubus) is one response, born out of modern fears, particularly in the face of nuclear destruction. Today such fears are extended to the fate of our planet through other developments, not least climate change, each of which similarly mocks our hopes and dreams. In the face of such perils and manifest crucifixions of life itself, where can we find faith? Dalí’s painting returns to the cross, to see in it, not only suffering, but ultimate assurance through divine transcendence.

Of course, Dalí’s imagery reflects his own, idiosyncratic, style and emphases. In particular, Dalí’s Crucifixion uses his theory of ‘nuclear mysticism’, a fusion of Catholicism, mathematics and science. Consequently, we see here Christ on a polyhedron net of a tesseract (or hypercube), alongside dreamlike Surrealist features such as the vast barren landscape and giant chessboard. Like John’s Gospel, Dalí’s intent is to encourage us to transcend immediacy and perceive deeper reality. Just as God in Godself exists in a space that is incomprehensible to humans, the hypercube exists in four spatial dimensions, equally inaccessible to the mind. This is the underlying truth of love behind the world, whatever we currently see or experience. Christ however provides us a human form of God that is more relatable, for Christ shows us God among us. Note well however, that this representation of Christ is also transcendent: a surrealistic levitating figure with a body that is healthy, athletic, and without signs of torture. For without denying the suffering, of which Picasso’s Crucifixion, and the Gospels also speak, Dalí, like John’s Gospel, points us to why this Friday is Good: for it reveals the ultimate force of love which can never be crushed, despite outer appearances. Note also, in the bottom left of the painting, Mary Magdalene, in the form of Dalí’s wife Gala, who witnesses Christ’s spiritual triumph over corporeal harm. At the painting’s edge, between the earthly and transcendent, she represents our humanity, called to bear suffering but to do so in the vision of ultimate truth, grace, and glory, uncrushable, even by the worst that earthly powers can do to us...

Where do we see crucifixion today? In John’s Gospel, in their colonial occupation of the Holy Land, the Romans clearly targeted Jesus’ people, the people of the land, named here (John 19.16b-24) by John as ‘the Jews’, though more accurately perhaps Judaeans in Jesus’ day. John’s Gospel’s use of ‘the Jews’ however strongly raises up for us questions of historic scapegoating, racism, and oppression, which are still very much alive here and across the world today. This is at the heart of F.N.Souza’s reflection upon Christ’s passion, produced in 1959 and entitled Crucifixion. For Souza was an Indian, who mainly worked in Britain, but was born in Goa, dominated in his youth by Roman Catholicism. He was deeply anti-clerical, yet, like Picasso and Dalí, his work reflects the power that Christ’s passion and archetypal religious images still have in the modern world, when released from over-predictable ecclesiastical captivity

Souza’s Crucifixion reminds us powerfully of both the offensiveness of Christ to so-called ‘normal’ or ‘polite’ society, and of the liberating strength of that divine offensiveness. Indeed, Souza himself had been expelled from colonial art circles in India with some of his paintings regarded as obscene, whilst later his prolific art receded in acceptability, partly due to entrenched racism. For central to Souza’s work were representations of other-than-white, suffering, male bodies.[3] No wonder then, that Souza’s Crucifixion asks us to see the crucified Christ again: no longer as one of the blond operatic Christs’ of the churches of his childhood, or of so many of our own; and Souza offers us a different image of masculinity. It challenges us to think and act afresh about the cross and issues of racism, decolonisation, and masculinity in our own day, reminding us of how, as on Golgotha long ago, God is in the midst of the horrors and hopes they bear. Souza’s Christ was of particular historical significance as a black Christ, exhibiting extraordinary enduring strength in the face of violence. Note well how in Souza’s portrayal, the figure of Christ becomes the tree of crucifixion, with its thorny branches, cum arms, extending across the image, and its feet, cum, roots set as firm supports for all that this tortured figure takes on, physically, emotionally and spiritually. However they treat you now, and divide your possessions, Souza is saying to all the oppressed, this is at the heart of your strength and your eventual salvation...

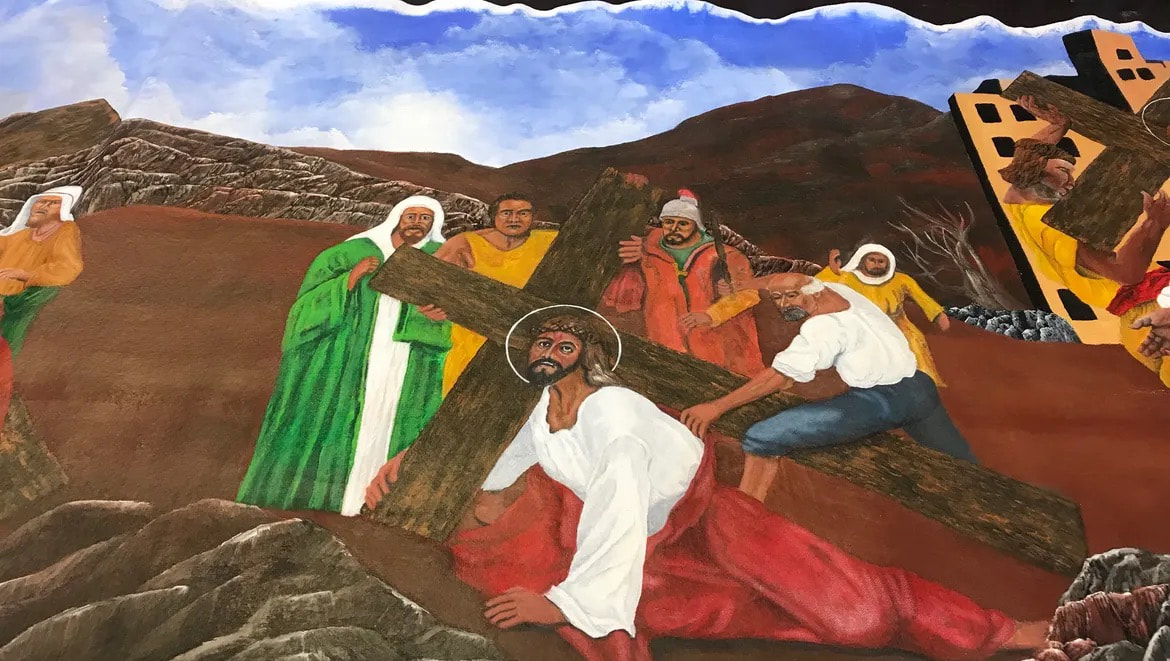

John’s Gospel does not provide us with Jesus’ dialogue with the thieves crucified with him and the reconciliation one of them finds in that. Instead, John gives us those words from Jesus for his mother and the beloved disciple which we have just heard (john 19.25-30). Yet these too centre on new relationship and, in some ways, complement the encounter with those, with Jesus, also labelled as criminal, and outcast to society. For, as we saw with Picasso’s Crucifixion, the cross challenges us to know the truth of life in death. As we saw with Dalí’s Crucifixion (Corpus Hypercubus), it invites us to reflect more deeply into ultimate meaning. As we saw with Souza’s Crucifixion, it calls on us to acknowledge continuing pain and liberating strength in racism and oppression today. But it also asks us to renew community, beginning with ourselves. This is the gift of our final picture, which is not so much great art, like those earlier images, but art in which we ourselves are called to share. For this is one panel from the Stations of the Cross painted some years ago by Tennessee men on Death Row.[4] It calls us, like Jesus on the cross, even at our limits, to reach out and enable fresh community. As we reflect on this, let me therefore conclude with a quote from one of the men involved:

This piece of art is a commentary on the continuing battle for our collective moral worldview. It is a collaborative effort with several of my fellow artists, all of whom reside on Tennessee’s death row. Not all are Christians or even religious. Several chose to be anonymous. I asked my fellow community members to help create this project to begin a conversation about what Justice looks like. When Jesus was executed, Justice looked different than it does today.

However, Justice today has some of the same components as it did back then. The guilty, as are the innocent, are subjected to this state-sanctioned process. As we understand it, state-sanctioned means that “We the People” — collectively speaking — uphold this system of Justice. So, based upon our support, this system of Justice reflects our community’s sense of morals and values.

One of the biggest issues my sense of the “Christian” world has is dealing with the fact Jesus was not Caucasian. This is also true here on death row, a microcosm of the larger “free-world” community. So we decided not to limit one another’s understanding of Jesus’ death or appearance... I do not know how many opinions we changed inside during this project, but the dialogue was open and honest, beyond what even I imagined. Safe, open dialogue is a prerequisite for the community model created on this death row. We invite dialogue from anyone on how to change the paradigms of our collective lives with those that promote healing and reconciliation within our diverse communities.

In the Spirit of Love, Mercy, and Forgiveness, Derrick Quintero

May we know that power of transformation so that Spirit of the cross of Jesus guide and strengthen us today and in the days ahead. Amen.

by Josephine Inkpin, for Pitt Street Uniting Church, Good Friday, 29 March 2024

[1] see further The Religious Art of Pablo Picasso - https://www.ucpress.edu/book/9780520276291/the-religious-art-of-pablo-picasso

[2] see Jane Daggett Dillenberger in The Religious Art of Pablo Picasso

[3] see further Dr Greg Salter’s lecture: http://pure-oai.bham.ac.uk/ws/portalfiles/portal/59326957/Salter_Introduction_Shaken_by_the_spirit_of_reconstruction.pdf

[4] See further https://www.redletterchristians.org/stations-of-the-cross/

RSS Feed

RSS Feed