In essence, Christmas is quite a queer thing - don’t you think? I don’t really mean its added oddities, like the 19th century, mainly English, extras, like the carols we sing, and the 20th century, mainly American, extras, like the exaltation of Santa. Those are aspects of Christmas down under which are part of our eclectic multiculturalism, even if they partly reflect our settler colonial culture and tend to work better in the northern hemisphere. For we have more than a little work still to do in listening to the Spirit in these lands now called Australia, including turning many of Christmas traditional symbols upside down and inside out. But that is less of a challenge when we truly celebrate the queerness of Christmas, especially in its original, biblically recorded, forms. For the stories of Christ’s birth - God made flesh - are, like queerness, full of extraordinary features, and very difficult to pin down. Indeed, the very idea that God is made flesh was, and is, a horror to many people. That means that matter matters, and, not least, our bodies matter – and every little bit of them – and caring for one another and our planet matters, because ‘matter matters’ and everything shares in this divine matter. Meanwhile, the idea that God is born in, and with, marginal and outcast bodies still seems so absurd and objectionable to many. For the biblical stories and symbols present God’s queer love: the ultimately irresistible power of Love which overturns all the neat boxes and boundaries of our oppressive world, and its typical ways of thinking. So, rather than trying to straighten out Christmas, as many people try to do every year, I believe that we are far better simply to enjoy its very queer ride: which involves keep adding to the oddities of this time of year, with fresh joy and creativity; and letting its divine queerness shine in us…

0 Comments

What’s in a name? - often, a huge amount. First Nations peoples are very clear about that and the intimate relationship between naming, language more widely, culture, identity and flourishing. Other oppressed peoples know this too. Hence the suppression or promotion of different languages is so vital an issue: just look, for example, at Wales, Catalonia, Belgium or Canada. It is not simply good manners to use the language people ask of us. It is because, unless we do so, we are disconnected from layers of meaning and identity, place and community, history and, indeed, geology. Take my surname: Inkpin. This has nothing to do with writing or being a scribe, or seamstress. It comes from two ancient British words: inga and pen. Inga, in modern English, means people. Pen means hill. This tells me, and others, that I come from the people of the hill, with all the deep layers of connection this entails: to particular soil and environment; to history and culture; to others, past, present and future. Indeed, even today, there are English villages, not surprisingly on hills, with the name Inkpen. For whilst much was swept away by the two great imperial invasions of my native land, there are still fragments of British indigeneity left, and one is my surname. It is a living reminder that there are other ways of being English, and British, than what is usually asserted: there are always were, and there always will be. For when we look more deeply, the living fragments of traditional cultures in every land call us both to recognition of pain and loss, and also to fresh pathways of justice. This is part of today’s Day of Mourning. We will not find peace unless we recognise what has happened in this land - and particularly in this city; unless we repent – and much more radically than we whitefellas have so far done; and unless, in Midnight Oil’s words earlier,[1] we ‘come on down’ to the makararrata place, ‘the campfire of humankind’, ‘the stomping ground.’…

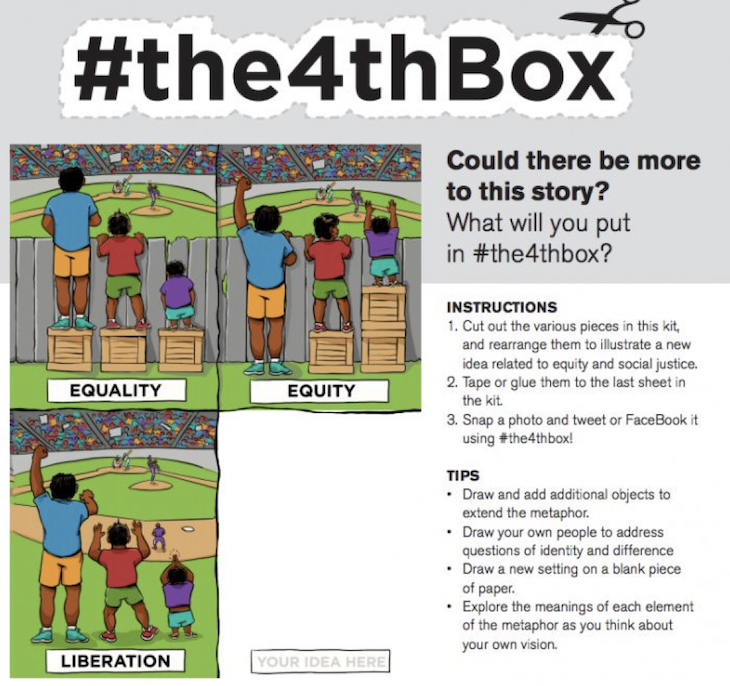

photo: by Ashin K Surash on Unsplash photo: by Ashin K Surash on Unsplash Today’s reading from Luke begins with the often-repeated phrase ‘don’t be afraid’. It is a phrase so often repeated that it has given me pause for thought this week. Do the Scriptures encourage us all the time not to be afraid, precisely because the people for whom they were written were in fact constantly afraid? They would have had good reason to be. As far as we can tell most early followers of Jesus were subject peoples living in occupied territory. The might of Rome was a constant threat, taxes were high, financial insecurity inevitable, and it was not as though they had the securities of modern medicine, analgesics, and antibiotics. Moreover, the expectation of Christ’s imminent return, coupled with an increasing impatience at its delay sounds an anxious apocalyptic note throughout the pages of the New Testament. But what about ourselves? Are we also afraid? Religion has after all for centuries traded in fear – fear of God’s punishment and condemnation, sweetened by the promise of salvation for those who truly believe, (some have called that ‘pie in the sky when you die’); treasures in heaven beyond the reach of moth, rust, and thieves – and after the last few months in Sydney I’d want to add mould! So, are we also afraid? This is an important question as we enter a period of considering our mission as a congregation. If we are afraid, what are we afraid of? – remembering that fear is not all bad. It is a great motivator to action. But the encouragement of the gospel is not to be afraid, but to act from a different place – a place where we don’t have supposed ‘treasures’ to defend; a place where we are set free from the need to control and secure; a place indeed as the letter to the Hebrews calls it, of faith... In recent years some of my Aboriginal friends have said to me that they do not really believe in the Australian concept of Reconciliation and some of the activities, like Reconciliation Action Plans, which have accompanied it. Meanwhile some Church leaders have said to me that they do not see much point in engaging actively in ecumenical endeavours. So why, we might ask, are we marking the Week of Prayer for Reconciliation and the Week of Prayer for Christian Unity this morning? Actually I did wonder about changing the title on the front of our liturgy sheet today to ‘Prayer for Just Relationships and Communion in Christian Diversity’. That, for me, would be at least part acknowledgment of the difficulties of the words Reconciliation and Christian Unity and the need for re-imagining as well as building on the good work of the past. However I have left Reconciliation and Christian Unity in the title for the present, so we honour where we have traveled. Nonetheless, as we hear our two readings this morning (from Revelation chapter 22 and John chapter 17), we do well to reflect more deeply on the words and constructions we may use in order that we share in more fruitful pathways for our work together with others. For that purpose I also offer you the cartoon meme entitled the #4thBox, as an encouragement to deeper prayer, more imaginative reflection and more creative action…

If, metaphorically speaking, one of the capital cities of Australia represented the earliest forms of the Christian Church, which would it be? One answer, for me, at least in terms of an old joke, would be Perth. For remember how that old joke went: in Sydney, they ask ‘how much money do you have?’ – little sadly has changed in recent decades; in Melbourne, they ask ‘which school did you go to?. in Adelaide – times have changed - they ask ‘which church do you go to?; and, in Perth, they ask ‘so what did you come here to get away from?’ Now, there is a good deal more to it than that. Yet, when they gathered together, there would have been a degree of truth in some of the earliest Christians asking one another ‘so what did you come here to get away from?’ That, as we can see from Gospel passages such as that we heard today (Mark 6.1-13), is part of the early Jesus movement story. It was also very much about where Jesus and his earliest followers were headed to. Yet what they were getting away from is vital to understand. For why did Jesus do no great deeds in his hometown? And why did he counsel his first followers to travel light, and be prepared to shake the dust off their feet, even if it meant enduring the metaphorical equivalent of crossing the Nullarbor?...  It is one of those lovely quiz questions, isn’t it – what do Barbados, Romania, the Ukraine and Scotland have in common? The answer is St Andrew of course, as their shared patron saint. In this COVID-19 year, that is something for which it is particularly important to wonder and give thanks. For in recent months we have, as a world together, been both divided by border closures, and united in suffering. On this Advent Sunday therefore, it is good to be reminded of our even greater connections in the immense hope to which St Andrew responded and shared with others. For Andrew’s witness is not least to the central importance of relationships, with God in Jesus Christ, with one another, and with the wider world. Today, as we celebrate the feast of St Andrew, and Advent hope, it is into such mission into which we too are called, and the joy which lies in such relational hope, beyond all the divisions and sufferings of our lives and world. Thus St Andrew should empower us to trust, and find new life, across our human borders and in the borderlands of suffering and joy, despair and hope… an address in favour of blessings after civil ceremonies for other than traditional male and female couples

at the Synod of the Diocese of Brisbane, October 2018...  In the opening pages of the excellent historical account of aboriginal dispossession in southern Queensland entitled, One Hour More Daylight, the authors reference a report by Native Police Commandant Frederick Walker . In July 1849 Walter engaged in battle with the Bigambul people of the Macintyre district. The report described protracted conflict and concluded with the words, “ I much regretted not having one more hour of daylight as I would have annihilated that lot.” It is a powerful phrase. It tells us at once two things. Firstly it tells us that across Australia and certainly in areas very close to here, the aim of early white settlers was not just to subjugate Aboriginal people. It was to annihilate them and remove them from the land entirely. This is our history. Secondly it tells us that the attempt to do this did not in fact succeed. Aboriginal people not only survived, they went on to contribute hugely to the culture and prosperity of modern Australia. This too is our history, but it is a history filled with struggle, ambiguity and pain that has to be acknowledged if it is to heal. It is a history of massacres, of the poisoning of wells and the deliberate exploitation of the defenceless. It is a history of the systematic destruction of languages, culture and ceremony and the connections that those things provide. It is a 230 year history of colonisation, dispossession and subjugation... Some of us may have heard that, on the same night as this year’s Sydney Mardi Gras, a gay man was beaten up in the centre of Toowoomba. This should not take the gloss off the rightfully joyful celebrations of 40 years of Mardi Gras, or the recent advance with marriage equality and all that that symbolises. Yet it is a vivid reminder, if we needed it, that there is still more to do. I say that with deep sadness, for after ministering for over six years in Toowoomba, I have seen that city become increasingly broad and beautiful, in its affirmation, not just tolerance, of our amazing Australian human diversity. So I am not despondent about Toowoomba, or anywhere else in Australia, even though we have just been recalled to the powerful forces of rage in our society…

Most of us probably know the old saying about some of the great Australian metropolitan cities: in Sydney, it is said, they ask ‘how much money do you have?’; in Melbourne, they ask ‘which school did you go to?’; in Adelaide, they ask ‘which church do you attend?’; and in Perth, they ask ‘so what did you come here to get away from?’ There is some truth in that even today. What then, I wonder, would be the question we would ask in Toowoomba? My hope is we would ask ‘what gifts do you have to enrich our world?’ This question is certainly at the heart of Jesus’ good news and behind today's Gospel passage about the nature of divine table fellowship. It is assuredly a great question for us on our parish thanksgiving weekend… |

Authors

sermons and reflections from Penny Jones & Josephine Inkpin, a same gender married Anglican clergy couple serving with the Uniting Church in Sydney Archives

June 2024

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed