flooding in Metro Manila

flooding in Metro Manila

flooding in Metro Manila flooding in Metro Manila Some years ago, I took a varied ecumenical group of young people to the Taizé Community’s International Gathering in the Philippines. For the first week, our group visited communities further north on Luzon island, including indigenous people displaced from their land. We were then billeted with local families in a poor neighbourhood of Quezon City in Metro Manila. I remember vividly how, after a typically wonderfully warm Filipino welcome, the first thing our hosts did was to point out the water marks high up on the walls of local streets: ‘that was from the last flood a month ago, they said, ‘sadly we are used to that kind of thing’. The impact of such experiences is powerfully transmitted in our contemporary reading today. It is echoed in so many places across the world, not least among the poor. It asks: ‘where is the God of Moses when you need them today?’...

0 Comments

“Let your gentleness be known to everyone. The Lord is near.” How fascinating! – the writer’s conviction that the second coming is at hand does not result in a plea for evangelism, or even for love, but rather for gentleness. So, what is to be gentle? The dictionary suggests, kindly, amiable, tender; or with more of a class nuance ‘of good family’ ‘noble’ – from the Old French from which we derive genteel. It is also a verb – ‘to gentle’ means to make less severe or intense, or perhaps to soothe by stroking; to treat with kindness and not cruelty. Gentleness is listed as the eighth of the fruits of the spirit in Galatians 5;22. As such it translates the Greek word prautes, which is sometimes rendered ‘meekness’, which has unfortunate connotations in modern English of servility. The Full Life Study Bible defines the word helpfully as ‘restraint coupled with strength and courage’...

I can trace my beginnings to a river. For once upon a time in England, in the difficult days of the depression just before World War Two, two men and a woman boarded a ferry across the Mersey – yes, just like the song! One of the men recognised the woman and introduced him to his friend, the other man. Every day as the three of them made their commute by ferry they would meet, and the woman and the second man grew closer. The second man went to war, but in 1942 he came home on leave and they were married. Then, or perhaps it was a different time of leave, the two of them went to the cinema, but the bombs fell as so often at that time. They sheltered under the great Liverpool St George’s Hall in the air raid shelter. But fearful of missing the last ferry across that river, they took a chance and raced to the shelter near the ferry terminal. That was the night the St George’s air raid shelter took a direct hit and all who had sheltered there were killed. Their need to catch the ferry saved the woman and the second man. In 1944 the woman gave birth to a baby – that child is my older sister. The river, and the ferry that crossed it brought my parents together, and without it, I would not be...  The contemporary mystic Andrew Harvey once wrote that ‘the things that ignore us save us in the end. Their presence awakens silence in us.’ I have been pondering this week whether this is what all wild places have in common, whether they be the Australian outback, other deserts, mountain places or wilderness forest. Regardless of the particularity of their wildness, wild places ignore us – in a healthy and health-giving way. In a wild place we cease, as human creations, to be at the centre of our own worldview and become aware of all that is beyond us. As the American Presbyterian theologian Belden C. Lane expresses it in his great work “The Solace of Fierce Landscapes: exploring desert and mountain spirituality”: 'There is an unaccountable solace that fierce landscapes offer to the soul. They heal, as well as mirror, the brokenness we find within.' When we find ourselves bereft of human company and resources, then we find ourselves in a place to let go of the demands of ego, the trivialities of our everyday lives, and to receive something of the incalculable and transforming presence of God... If you were only allowed one book from the Hebrew Scriptures, which would you choose? It would be a tough selection, wouldn’t it? At the risk of being called a Marcionite, there are a few books I might dispense with quite cheerfully: not least Leviticus (that continuing bane of some people’s lives) and also Numbers, and perhaps Ezra and Nehemiah. Personally, I’d also be happy to see quite a few other passages put to one side, including the invasion of the land by Joshua. However it would be hard to choose just one book to keep. For Isaiah would be high on my list, together with Genesis and the Psalms, Lamentations and some of the other prophets. In the final analysis however I’d pick Exodus: a book which begins with abject slavery and ends in the glorious presence of God. Along the way, we see all kinds of adventures, highs and lows, encounters and transformations, betrayals and revelations, miracles and mercies: all ending in today’s vision of clouds and glory. Such a core story which encompasses so much about living faith! What a perfect prelude today to this Sunday’s feast of the Transfiguration….

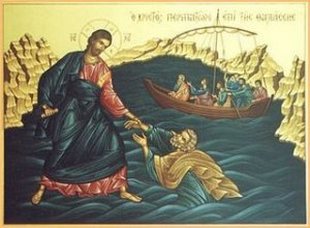

What mountains do you know? Mountains are among the most treasured and admired locations on earth - as well as some of the most perilous. I wonder what are some of the mountains that you have heard about or even visited yourself? What are some of the things you love about those mountains? We've heard about a few mountains here in Australia, some of them local to Toowoomba and to Queensland, and about some mountains far away. Through our links with Nepal we have particular connections to the Himalayas and of course to the world's highest mountain, Mount Everest. Has anyone climbed a mountain that really required the proper gear, ropes and grappling irons and all those things? Climbing a mountain requires a lot of effort, and preparation and discipline and persistence - which is why climbing a mountain is such a good picture for the spiritual life and often used as such. It is also why some traditional Christian communities are located near the top and on the very edges of mountainsides. Climbing requires patience and faith and provides a sense of perspective. When we physically get up higher we can see more; in the same way the more we advance in our relationship with God the better perspective we have on what really matters in life...  by Jon Inkpin, for Pentecost 12A What do you make of religious experience – not religious ideas, religious morals, religious activities, but religious experience? Does it make you awkward, uncomfortable, even embarrassed? Many secular people find it to be so. Even many Christians avoid talking about it. To a degree, this is understandable. Religious experience can be very intimate and personal. It is not always something we want to hawk about and have discussed in public. It is after all a holy thing, and St Paul warned us not to throw holy things before the ignorant, the swinish, lest they be trampled underfoot. It can also be misused, like those Christians, and others, who sometimes tell us that unless we have their kind of religious experience – perhaps their kind of conversion or charismatic experience – then we are not Christians, or acceptable to God, at all. All that, as I say, is understandable. Yet, if it keeps us from religious experience, or reflecting on our religious experience, then it is a huge problem. For, as we see in today’s great story of Moses and the burning bush, religious experience is central to our Faith. Encountering the living God is not an embarrassing extra to life. It is at the heart of our being and our becoming. For, as Saint Augustine said, our hearts are ultimately restless until they find their rest in God...  by Jon Inkpin, for Pentecost 11A, Sunday 24 August 2014 Most of have probably heard of Mahatma Gandhi. What however does ‘Mahatma’ mean? It was not the real name of the remarkable 20th century Indian leader called Gandhi. His name was Mohandas Karamchand Gandhi. The honorary name Mahatma was given to him because of his amazing character. Indeed, it was given to him when he was a lawyer in South Africa, especially for his deep concern and work for the poor. For the name Mahatma comes from a Sanskrit word which means ‘high (or great) soul’. In Christian terms, we might say ‘saint’, or, simply, one who is ‘great hearted’. Whom would you name Mahatma today? Whom do you see as ‘great hearted’?...  by Penny Jones, Pentecost 9 Year A At first sight it may seem odd that the lectionary brings together today the two great stories of the selling of Joseph into slavery and of Jesus walking on the water and saving Peter. They are both rich stories, full of connection to our own lives of faith, yet what unites them? Well let's notice first the parallels between the story of Joseph and the story of Jesus - parallels that would have been immediately obvious to Matthew's readers, which we tend to forget. In both their stories we find the motif of the hero who is envied, betrayed, left for dead and yet rises again. Joseph is betrayed and sold by his brothers for twenty pieces of silver. Judas who was a shrewd keeper of the purse obviously allowed for inflation when he betrayed Jesus for thirty. Both stories are telling us that spiritual leaders who claim a direct line to God and speak truth to power, tend to find themselves very unpopular. Indeed there is that in human nature which seeks to kill the divine when it is seen in humanity. We recognise the truth of this as we look back over history to the great martyrs of our faith, all of whom have suffered and died for their refusal to accept the ways of the world. So the story of Joseph is if you like an archetypal story, a story that reveals patterns of human behaviour that are true for all times and places. And his story foreshadows the story of Jesus, just as the stories of later martyrs recapitulate that same story, tell it over again. It is a story of dying and rising. A story whose pattern is recognised and known deep within every human being, and found in its simplest form in our own bodies' rhythms of inhalation and exhalation. This is why the story has power for us, because it is our story, our truth that gives shape to our living...  Lent 3A, Sunday 23 March 2014 by Penny Jones The marvellous Celtic poet and mystic John O'Donohue described faith as 'the absolutely irresistible longing for God'. This is why Jesus in today's gospel describes himself as 'living water'. For every human being on this watery blue planet of ours has an irresistible longing for water. We literally cannot live without it. Indeed almost all of our bodies is made up of water. The longing and thirst for water is more desperate than the longing for food, or sex or companionship or home. Thirst is an elemental, irresistible longing. We need water. And not just physical water. Moses led the people out into the wilderness and they became thirsty. There was no water for them to drink. So of course they complained. In that barren place they experienced their need, their dependence on God. And through Moses, God satisfied their physical need, striking water from the rock so that they could drink. The experience of wilderness, of longing and thirst is essential to our mature spiritual growth... |

Authors

sermons and reflections from Penny Jones & Josephine Inkpin, a same gender married Anglican clergy couple serving with the Uniting Church in Sydney Archives

June 2024

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed