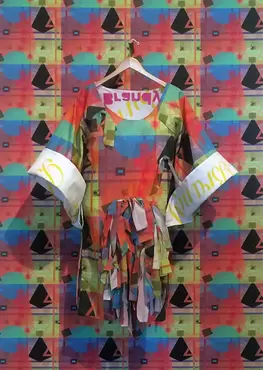

image: Brandy Martell, 400 block of 13th St near Frankland St, Oakland

image: Brandy Martell, 400 block of 13th St near Frankland St, Oakland Firstly, true resurrection, like great art, involves ‘telling it slant’. For how otherwise do we describe resurrection without descending into cliché, or worse still, propaganda? As my most favourite former bishop famously put it, ‘resurrection is so much more than a conjuring trick with old bones.’ We do well to avoid the old quarrels between literalists and rationalists, centred only on Jesus’ body, or the empty tomb. The Gospel resurrection stories seek to picture the power of divine transformation of which Jesus’ resurrection is crucial, but only the first fruits. For the women in Mark’s Gospel fall into silence at the fearsomeness, or we might say the awesomeness, of the power of God: the astounding power of divine love which can turn all things upside down and inside out, even death and all that denies life. Understandably, we want to ask questions: what exactly has happened? what is the nature of the resurrected body? where has Jesus gone? The other Gospels, and verses added to the first manuscripts of Mark’s Gospel, offer us a variety of stories to help with this, each however pointing symbolically and metaphorically to deeper meaning. For the real question for Jesus’ first followers, and all of us since, is how do we respond, and where will this all end? Indeed, that question ‘where will this all end?’ is that of the Mayor in Graham Greene’s story Monsignor Quixote, the end of which we also heard read just now. Like the women in Mark’s Gospel, the Mayor had been so impacted by divine love, that, despite Father Quixote’s death, his life had been transformed. So, he wondered, ‘with a kind of fear’, like the women impacted by the divine love of Jesus, despite the reality of death, where would this love take him?

resurrection as mystery

For, secondly, true resurrection rests on mystery. Indeed, how do we communicate resurrection without such openness and elusiveness? Symbolically, the point of the story of the empty tomb is surely that it is empty: that it breaks open the death-dealing ways in which we confine life and meaning, and accept the closure of all the other possibilities there may be. To put it another way, human beings spend so much time trying to kill off the living God, where we do not find ways to hide from them. The Resurrection affirms that we can try to shut God up in any way we like. The God of Love will however always find a way out. Monsignor Quixote may not have been the greatest of Graham Greene’s novels, which typically wrestled with powerful Christian themes of life and death, goodness and evil, corruption and salvation, in edgy modern contexts. Yet, in a more comedic style, it sought to offer light and hope beyond the historic betrayals of religion and politics. So a flawed priest and a disappointed Communist are drawn together, through a pastiche of Miguel de Cervantes’ great work Don Quixote, into an adventure of love. As we heard in the excerpt earlier, the results displease both religious authority, in the form of the bishop, and skeptical rationalism, in the form of the professor. Both of course are interested in certainty, of different kinds. The adventure of divine love makes no sense to religious dogmatism or secularist rationalism. Yet, as the Resurrection proclaims, life and death are just not so straightforward. Rather, there is always the possibility of divine surprise, for, as Father Leopold says in the novel, we are always ‘faced by an infinite mystery.’ No wonder the Mayor, like the women in Mark’s Gospel, was perturbed, and honestly admitted ‘I’m rather afraid of mystery.’ Aren’t we all, if we are honest? For resurrection, the experience of divine love even in and beyond death, transforms us, and invites us into fresh adventures of love.

resurrection as experience

This is because, thirdly, true resurrection revolves around experience. For how do we live resurrection without knowing, and honouring, our experiences of divine, transforming love. The Mayor in Monsignor Quixote puts it well: ‘Why is it’, he said to himself, ‘that the hate of man – even of a man like (the great Spanish dictator) Franco – dies with his death, and yet love, the love which he had begun to feel for Father Quixote, seemed now to live and grow in spite of the final separation?’ This is at the very heart of the Resurrection, for the women and others in the first Christian century, and every since. For we may be traumatised, even seemingly utterly devastated, by death and destruction, just like the first followers of Jesus. Yet the love we have shared, the deep-down love that we call the love of God, can never be denied. It will break out again, even in extraordinary ways. We may then, like the women at the tomb, be overcome by awe, but we will then find our voices again, for we have been transformed, and cannot deny that transformation. And in this, in our own lives, and in our own bodies, we are then visible signs of resurrection, which will break out of every tomb and find new forms of transforming expression.

resurrection as trans-formation

Let me conclude with a powerful example of lived resurrection in the transgender community. For today, as well as being Easter Day, is also the Transgender Day of Visibility. That, for me, is a happy connection, for so many trans people are themselves living signs of resurrection, with bodies transformed from death-dealing to life-bearing, sharing in the joy and openness of love’s transformation. On the front of our liturgy sheet this morning, you will therefore see an image from an artistic initiative called Project 42.[2] The number 42 relates to what was calculated to be the life expectancy of trans people in the USA and the project memorialises those trans people (typically black and female) who are killed every year from violence. The image you see is from a garment beautifully created in honour of one particular victim. For clothing is of particular significance to many trans people and their/our identities. Yet these garments are not just grave clothes, and those who died – we might almost say crucified for who they were – are not just victims. For these garments, like the grave clothes the women saw at the empty tomb of Jesus, are actually signs of resurrection, as the life and love they honour are raised up and live again in the lives of trans people and those who see them. For if we share true resurrection, we do so: like artists, telling it slant; receiving the mystery of love that can never be defeated; and witnessing to its transforming power in the living of that great divine adventure. In the name of the transforming One, who was, and is, and is to come. Amen.

[1] full poem at https://www.poetryfoundation.org/poems/56824/tell-all-the-truth-but-tell-it-slant-1263

by Josephine Inkpin, at Pitt Street Uniting Church, Easter Sunday 31 March 2024

RSS Feed

RSS Feed