Have you ever thought about the silence of the men in the Lucan birth narrative? While, as we have been exploring in our Advent reflections so far, the women are for once dominant in the Biblical narrative, the men are by no means inconsequential. They are however largely silent. Zechariah is literally (well, probably not literally, but for the purposes of the story literally) struck dumb, and Joseph is described as planning to act ‘quietly’. If Pascal is right, and “all of man’s (and I’m naughtily keeping his non-inclusive language deliberately here)- all of man’s misfortunes come from one thing, which is not knowing how to sit quietly in a room”, then these two men, Zechariah and Joseph, are definitely quieter than most.

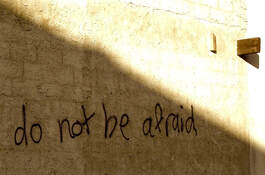

Their stories, like those of Mary and Elizabeth, are designed to mirror and amplify each other. Both feature dreams and angels, and changes of heart. Why I wonder do we not call them “the annunciations”, for they just as much as Mary are visited by an angel and asked (or for Zechariah, more accurately ‘required’) to give their consent? Both reveal men of faith, struggling to understand what is happening to them and accepting their own powerlessness with differing degrees of readiness. Joseph heeds more easily the angelic word ‘do not be afraid’ and his initial confusion and rejection is quietly transformed into solidarity with whatever God is doing. For Zechariah the path is different and there is a harsh note to the angel’s declaration - ‘because you have not trusted my words, you’ll be mute’ – that makes me rather wary of the Zoom host’s ability to silence others – sorry all those of you currently mutely listening in!

silence and Zechariah

Why did the angel silence Zechariah? Was it possible that keeping quiet was a form of spiritual purification that Zechariah needed to undergo to become a better priest? Could it be that silence was the necessary condition that Zechariah needed so as to have the space to ponder and reflect upon Gabriel’s powerful message?

Was the inability to talk, a means for Zechariah to fulfil the destiny implied in his name? For names are very important in the birth narratives as elsewhere in scripture. Zechariah would have been named for the minor prophet Zechariah, who along with Haggai encouraged the rebuilding of the temple after the return from exile in 516BC. That prophet is described as ‘Zechariah, the son of Berechiah, the son of Iddo’. Zechariah means ‘God remembers’, Berechiah means ‘God blesses’ and Iddo means ‘timely’, so putting that together the prophetic message of Zechariah in the Hebrew scriptures is that ‘God will remember and bless at the right time’ . Well the right time in the New Testament text is right now, with this new Zechariah, who speaks out of his imposed silence at Luke 1:62-64 where he “asked for a writing tablet” and wrote, “His name is John”. So simple, yet so profound, reiterating Elizabeth’s wishes as well. On the face of it, Zechariah had to write on a tablet simply because he could not speak. However, I believe that Zechariah’s simple act of writing reflects something far more profound: a making visible and tangible of love and faith. By naming his son John and in turn, fulfilling not just Gabriel’s prophesy but the prophecy of the whole Hebrew scripture embodied in Zechariah’s own name, Zechariah regains control of his speech. By letting go of his need to control, to speak and to know, Zechariah receives a tangible sign of faith – one that “amazed” his “neighbours”, one that would shape his future priesthood, taking it beyond scrupulous observance and to a place where he could shape and support the emergence of his prophetic son John. Out of enforced silence, comes more powerful speech.

Christianity's deep ambivalence with silence

As has been well expressed by Diarmaid MacCulloch in his fine book Silence: A Christian History (expanded from his Gifford lectures which I commend to you), Christianity has a deeply ambivalent relationship with silence. And perhaps we all do. Whether it is the scriptural disjunct between the ‘truly my soul waits in silence for God’ of Psalm 62 and the injunction of Psalm 109 ‘do not keep silence”, or the balance in our hymnody between ‘tell out my soul’ and ‘let all mortal flesh keep silence’, Christians are not sure whether to speak out or keep quiet! And while with Meister Eckhart we may want to affirm resoundingly that ‘nothing is so like God as silence’, there can be no doubt that silence in churches around such issues as slavery, the holocaust, and clerical abuse, alongside the silencing of non-hetero-normative, non-male voices, is deeply troubling. Here in many of the churches of Sydney for example the voices of women and queer Christians are silenced. In reviewing MacCulloch’s book for the Guardian, Stuart Kelly writes:

MacCulloch delicately balances the attractions of the via negativa with a concerned awareness that retreat from the world can also be a capitulation to its power and its prejudices, a spiritual solipsism. To that extent silence here functions as a metonym for the wider Christian paradox of engagement with and withdrawal from the world.

withdrawing to engage

Zechariah withdraws in order to engage. So does Joseph in his own way. Both exhibit an evocative, loving restraint, in their responses, that allows the voices and the stories of the women to be heard. Imagine, as our contemporary reading today suggested, if more powerful men were wordless Words! Their truthful restraint is not what we often see in parliament or among the trolls of social media these days. True restraint is part of male and wider human strength for it reflects divine strength - allowing others to speak, to be, and to love.

silence and speaking out in the White Ribbon movement

Some of you will have noticed that Lorrie has added white ribbons today to the tree of hearts that last week we introduced to symbolise the Magnificat – the magnifying of God’s revolutionary love in the world. White Ribbon is the world’s largest movement engaging men and boys to end male violence against women and girls, promote gender equality, and create new opportunities for men to build healthy, positive and respectful relationships. On white ribbon day, the 25 November and whenever white ribbons are worn, men, women and all diverse identities are encouraged to stand up, speak out and say ‘no’ to gendered violence of all kinds. To say ‘no’ to – the violence of speech as well as action; the violence that silences non-male voices; the violence that keeps quiet when speech is needed as we have seen in political life in recent times. We need silence – and powerful speech; withdrawal and engagement.

The history of this movement tells its own story. The 25 November was chosen in 1981 as the International Day Against Violence Against Women by the first feminist Encuentro or meeting for Latin America and the Caribbean to commemorate the lives of Patria, Minerva and Maria Teresa Mirabel who were violently assassinated on 25 November 1960 after years of dictatorship in the Dominican Republic. On December 6, 1989, a male student entered a classroom of the University of Montreal, shouting anti-feminist slogans and fatally shooting fourteen women and injuring ten more. In response to this Canadian politician Jack Layton is credited with beginning the white ribbon Movement and two years later The Centre for Women’s global leadership called for a global campaign each year of sixteen days of activism against gender violence, to run from 25 November to 10 December – so we are only a little late!

silence and engagement in the age of John and Jesus

The world into which John and Jesus were born was violently patriarchal. Women enjoyed very few rights. As a woman who had become pregnant while unmarried, Mary could have been stoned to death and certainly cast out from the community. Elizabeth as an older vulnerable woman, long understood to be barren, could have been subject to many supposed jokes and more dangerous slurs against her reputation. The men in their lives, Joseph, and Zechariah, protected them. They were – to use an old-fashioned term- ‘gentlemen’ (rather like my father-in-law) who stood themselves in the gap between the censure of the world and the women entrusted in that culture to their care. Their protective actions speak louder than their words could have done. The relative verbal silence of those men enabled the women to speak; enabled the divine Words to be born in them. Silence – but also engagement and action. Their silence and their engagement inspire us.

Advent and silence

In this Advent season – a time often inundated with noise, hustle and bustle – may we also intentionally carve out times of silence. And may such times of quiet help us listen courageously and respond generously to God. May we learn from the restraint of Zechariah and Joseph and allow the Word to grow in us through our very wordlessness, that when the infant, the Word without a word comes to us this Christmas we may no longer be silenced, but proclaim from the housetops the Hope that we know. Emmanuel – God with us, speaking and silent. Amen

by Penny Jones, for Sunday 12 December, at Pitt Street Uniting Church

RSS Feed

RSS Feed