Secondly, this passage from Ephesians is, in my experience, somewhat deficient in some crucial aspects: namely how anger relates to justice and to God. For, as I’m going on to say, the advice in this reading is very helpful spiritually. Yet it does not deal well with the burning anger which we and others can feel about injustice, towards ourselves or others. Nor does it tell us enough about what to do with our anger in our relationship with God, as distinct to other human beings. To be honest, I suspect that is because Ephesians as a whole is an example of how, even in the New Testament, the prophetic dynamic of Jesus for justice has often been watered down by other concerns for order and unity which have been given greater priority. So, whilst there is much of spiritual value in Ephesians, its understanding of anger is tempered by its interest in propriety. In chapter 5 we can thus go on to read about how the writer believes wives should be subject to their husbands: teaching which has often been used to prop up gender injustice throughout Christian history. Similarly, in chapter 6, we can read of how the writer believes slaves should be subject to their masters: again something which helped Christians to justify slavery until less than 200 years ago. Such inequities understandably breed anger. What then are we also to do with God if God is tied up with this? Even if such injustices are not God’s eternal will, what on earth, we may feel angrily. is God doing about them? In other words, in reading this passage together, what I am suggesting is that we need both to question and honour the words of our text - something which it is almost always wise to do with any scripture if we are genuinely to seek God’s love and intention for us within it.

So, after these questions and reservations about the text I offer to you, let me say something about what is truly valuable about a Christian approach to anger which both builds on Ephesians opening up of the subject, and builds upon it…

Firstly, as in this text, Christianity accepts anger as a perfectly natural emotion, one to be expected. This is not something which all religious or philosophic teachers, even some Christian ones, have accepted. Many Buddhists for instance believe that anger – even righteous anger – is not healthy. In contrast, Ephesians 4.26 is quite forthright: ‘Be angry’ the writer says, even though they are primarily seeking order and unity based on peace and quiet. For, even if the writer was seeking to soften the spirit of Jesus for his own context, they could not deny that anger is both intrinsically human, and divine. For uncomfortable though it often is for us, Jesus was sometimes full of anger, wasn’t he? – both in some of his words (for example in calling Pharisees ‘you brood of vipers’) and some of his deeds (as when he overturned the tables of the money-changers). Even the order-seeking writer of Ephesians therefore acknowledged that sometimes it is right to feel anger – not just because it is human to do so, but alos because we may sometimes be acting like Jesus in doing so, especially where we are concerned for justice, as all God’s children should be.

There is a vital aspect of biblical faith however that Ephesians is not telling us about in its teaching about anger: namely the necessity of being angry with God. This is found in many places in the Bible, isn’t it? – not least in the Psalms, which are full of cries of anger, about pain and injustice, directed towards God. Why, O God? How long, O God? What on earth are you doing, or not doing, O God? We aren’t reminded about this often, are we? – yet a crucial part of honest prayer is the ability we must develop to share our anger with God: not just because it is a way of unloading our anger, but because God, quite frankly, is part of it all. Of course, we may still have to listen,. Like Job, to an uncomfortable answer from God which can lift us from, or re-direct our anger. Yet being, healthily, angry with God, wis part of our spiritual journey and growth.

Secondly, we are to practice forgiveness: or, as Ephesians 4.32 puts it, in our reading today, we are to ‘be kind to one another, tender-hearted, forgiving one another, as God in Christ has forgiven you.’ This is part of the transformative power of prayer, even angry prayer. It is not a matter, for example, of forgetting injustice but of holding it in a way which takes away the debilitating power it can have upon us. Note well: this is not by our own effeorts but through the grace of God in Christ that we can learn to be kind, tender-hearted, and forgiving to others and ourelves, even when others are continuing to hurt us. For to follow and be transformed by God in Christ Jesus is to learn mercy as well as seek justice: mercy and justice walk hand in hand, just as peace and righteous anger do. It is in this spirit that the words of this passage in Ephesians makes sense: not to let the sun go down on our anger; to use words which build up and give grace to those who hear; to seek to live in love. For this is to live, as the writer pouts it, as ‘imitators of Christ’, living in love as ‘a fragrant offering and sacrifice to God’ for that is what Christ has done and modeled for us.

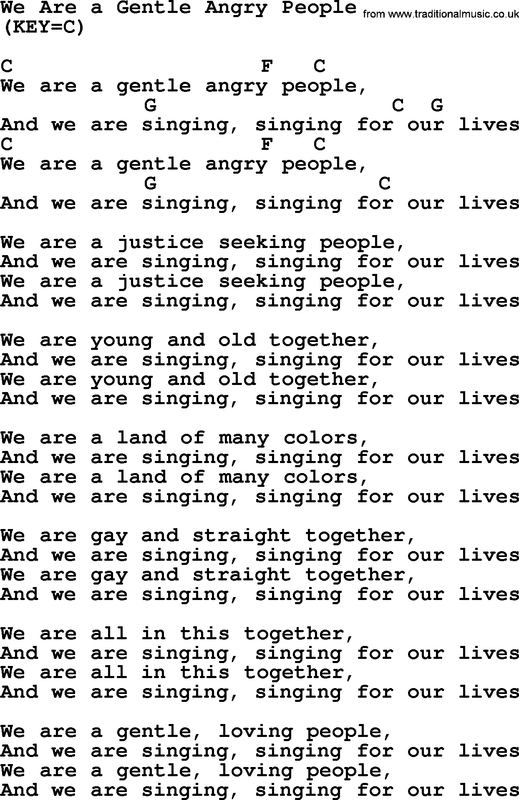

Express righteous anger and practice forgiveness then, as this passage encourages, but also do something else, which this text does not develop, yet which is perhaps implicit in the direction to ‘live in love: namely, as the prophet Micah put it ‘do justice, love mercy, and walk humbly with your God.’ One of the great inspirations of my life, and my chosen namesake, Josephine Butler put it in her own context like this: driven by righteous anger, as well as love, for the plight of suffering women, men and children in her own day, she would counsel those Christians who sat on their hands to action – ‘Tears’, she would say, ‘are good. Prayers are better. But best of all is the ballot box (by which she meant social and political action and change). For God does not allow us to have anger without any cause. Like pain in our bodies, it is there because something is wrong: in ourselves, in the we are living, or in the things others are doing to us or to others for whom we are concerned. We are therefore not to avoid anger, any more than avoiding pain will make things right. Anger, like pain, may then just fester and destroy us further. Rather we are to hold our anger tenderly, express it to God and be strengthened by God’s grace. For Christians, as the old Christian peace song put it, are to be ‘gentle angry, loving, people, walking with our God.’ In Christ, Amen.

by Jo Inkpin, for Pentecost 12 Year B, Sunday 12 August 2018, on Ephesians 4.25-5.2

RSS Feed

RSS Feed