image: The Incredulity of Saint Thomas by Caravaggio

image: The Incredulity of Saint Thomas by Caravaggio Let us therefore look again at Thomas. Have you ever wondered why the adjective ‘doubting’ has stuck? I mean, we don’t usually call Peter, ‘Denying Peter’ – though, if we did do that a little bit, we might mitigate the claims to truth and power historically made by some Christians in the name of the alleged authority of Peter. Have we forgotten that, especially among Indian Christians, Thomas is recognised by many as one of the great Christian missionary leaders? Looking at this text, why do we not also call him ‘Affirming Thomas’? After all, his confession of Christ is at least equal to Peter’s, or anyone else. More vitally however, if we are serious about learning from this story, we should really call him, not so much ‘Doubting’, but ‘Bodily Thomas’ – or, as they might say in Wales, Thomas the Body. For Thomas centres us on the bodiliness of Christ: in the resurrection, as in Jesus’ life. No wonder then so much theology has been obsessed with Thomas and doubt. It is a bit of a conjuring trick. Reflection on ‘doubting’ Thomas distances us from Christ’s body, and our bodies, and makes us obsess about belief. Instead of what we see and feel with all our senses, in our hearts, and on our skin and in our wounds, we settle for intellectual conversations in our minds. All too often, reflections upon the Resurrection’s extraordinary bodily and holistic implications thus become mind and power games. The Resurrected Body of Christ becomes spiritualised, intellectualised, and, removed from us.

In today’s world of multi-faceted trauma and contested bodies, we might let the doubting Thomas adjective lie, at least for the time being. Instead, let us look at this Gospel passage afresh. Beyond the intellectualised faith-doubt framework, what does it then say to us? In particular, what does it say in and through our bodies, and the wounds and other experiences of life we carry? Where do we feel this story in our bodies and in the whole of our selves?

One recent theologian who invites us to approach this text differently is Shelly Rambo, Associate Professor of Theology at Boston University. Indeed, her book Resurrecting Wounds centres on it, with the telling sub-title Living in the afterlife of trauma. That is why we used the title Resurrecting Wounds for our recent trauma workshop. For Rambo’s work is part of a re-shaping of Christian Faith which takes seriously our world’s diverse bodies and multiplicity of wounds. Rather than the often deadening cul-de-sac of ‘doubting Thomas’ fixations, this values the resurrection’s bodily aspects and offers new life through them.

body and wounds

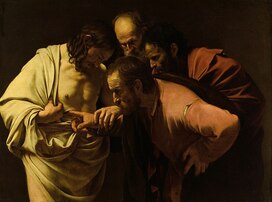

Let me briefly highlight three ways Rambo sees today’s Gospel differently and helps us find healing in it. Firstly, the story of what I prefer to name as Bodily Thomas directs us back to the scandal of the incarnate God of Jesus, to bodies and wounds. For it we are not shocked and surprised by this story, we should be. It is a very indecent tale, full of icky embarrassments, especially the very fleshly wounds of the risen Christ. Like the very embarrassing details of Jesus’ birth and bodily contacts with indecent people, no wonder Christian theologians have tried to tidy this narrative up. They are not the only ones. The text itself does not indicate whether Thomas actually takes up Christ’s invitation to touch the wounds. Therefore the great artists, including Rembrandt, have typically left a distance between Thomas and the resurrected wounded body of Christ. Caravaggio was an exception. In his great painting The Incredulity of Saint Thomas, he places Thomas finger within the wounded body. Few theologians until recently have done the same. Instead, as Rambo highlights in relation to Calvin, the tendency has been to distance the resurrected Christ from the flesh and continuing struggles of the world. Emphasis is placed on victory, glory, and ascension without wounds.

The result of traditional dominant approaches is therefore to contribute to what J. Kameron Carter has called the vast disembodiment on which so much of today’s modern thought is built. The practical consequences are seen in the wounds and trauma of those whose bodies are marginalised: whether by reason of gender, race or other feature. As Carter put it in his book Race: A Theological Account:

The aesthetic imagination of the modern intellectual is conditioned on obfuscating the real world of pain and trauma as the condition of thought.

Like Rambo, and queer, dis/ability, and postcolonial theological voices, such vital Black theologians call us back to the scandal of the incarnate God and their liberating love. As Carter again says, theology:

must do its work in company with and out of the disposition of those facing death, those with the barrel of a shotgun in their backs, for this is the disposition of the crucified Christ, who is the revelation of the triune God.

In other words, the Thomas resurrection narrative directs us to God in and through our wounds, not to simple escape from them.

healing and resurrection scars

Secondly, approaching today’s narrative with trauma-responsive eyes helps us rediscover the Gospel’s healing power. Whereas much received theology erases so many bodies and their wounds, Bodily Thomas’ encounter with the resurrected Christ helps us find fresh hope: touching God, literally, as well as metaphorically, in and through our wounded bodies and world. What a welcome message of good news that is! For today we all live with trauma of various kinds, including the political traumas of various forms of violence and exclusion, and possible nuclear or ecological destruction. A living Faith needs to speak out of, and into, these experiences. This requires revisiting our foundational narratives which have been so distorting. That is what body-aware theologians are saying. Rambo illustrates this in re-telling the ancient story of Macrina. Her brother, the great theologian Gregory of Nyssa recounted how after her death, her mothers’ touch revealed the scar of Macrina’s own healing from what we would now likely call breast cancer. The tumour was removed but the mark remained. In so doing, even in death, through the loving touch of others, Macrina’s body shone with resurrection, healing, light. Yet we do not have to go back into tradition to see such resurrection among us. We only need look at signs of resurrection in the bodies around us, including those in the Queer Faces of Faith portraits which have been hanging on the wall as part of the Amplify Queer Faith project.[1] For if you want to see the Body of Christ alive today, look for a start at the portrait of non-binary Pastor Steff Fenton, whose scars from chest surgery, like those of Macrina, display the transformation worked by divine love.

Rambo invites us to approach our own, and the world’s wounds in a similar way. Much like Christ's wounds and Macrina's scar, all kinds of wounds are found on the skin of our personal and collective lives. Not least, the wounds of racial histories, unhealed, resurface again and again. The wounds of war, gender and sexual violence similarly persist and are felt on, and in, too many skins and bodies. Despite the best attempts at erasure, theological and political, such wounds cannot be simply wished away. Instead, we need to learn how to heal. In this, the visceral display of Jesus' wounds, when seen at the centre of Thomas' encounter, enacts a vision of resurrecting that addresses our deep wounds and offers us possibilities of hope and healing. Like Thomas in the story, our learning is not to turn away from wounds, but to touch and be touched by love, and trust in divine redemption. Instead of focusing on Christ’s after life, we can then find ways of flourishing in afterliving beyond our wounds and trauma.

covenantal community

This brings us, finally, to a third contribution of trauma-responsive theology to re-seeing Thomas’ encounter and thereby re-shaping our faith and world. For, in Resurrecting Wounds, Rambo invites us to place Christ-like community back at the heart of our lives. She points out how Thomas’ experience of resurrection is not only about facing up to our wounds and trusting in God’s loving touch and presence. It is also, vitally, nurtured in communities of redemptive suffering. Note well therefore, in Caravaggio’s painting, how Thomas’ healing and trust in God is wrought in relationship with others. For we only fully heal and thrive in relationship. J.Kameron Carter calls this ‘intrahuman identity’: as, in his words, ‘in receiving onself from one another…. one in fact receives God and is most fully oneself.’ In this, and not through levels of belief or doubt, do we live out the Bodily Thomas narrative, becoming one with the actual covenantal body of Christ.

Let me leave you with some words from a fellow transgender priest, Canon Rachael Mann, from her book Dazzling Darkness: Gender, Sexuality, Illness and God. This expresses something of what Thomas the Body discovered as he passed his hands through the suffering of Jesus into the promise of the resurrected Christ: the discovery that God’s grace works through our bodily wounds, transforming us in this life, and a whole lot more beyond, into the glorious body of Christ. For Rachael’s own journey, as she puts it, through:

‘bouts of wild living, endless self-indulgence, a sex change, questions about my sexuality, and nasty, nasty chronic illness – has been nothing more or less than an adventure in becoming more myself in the wholeness that is God. It has been, and is, an adventure into places of both joy and considerable pain. It is a journey down into being – into being me by being in God. It is a mystery of connection – the more I know God, the more I know me and the more I know me, the more I know God. It is also a journey into a kind of terror… discovering that somehow … in my messy brokenness… I am most me. It is into this place that Christ comes, the Christ whose wounds never heal, though she be risen; the Christ – the God – who holds the wound of love within her very being. For, so often, it is our very woundedness, our vulnerability, which feeds and heals us.’

In such vulnerability, in our own woundedness, in the body of Christ together, may we indeed, like Thomas, be fed and healed. Amen.

by Josephine Inkpin, for Pitt Street Uniting Church, Sunday 16 April 2023

[1] https://www.amplifyqueerfaith.com.au

RSS Feed

RSS Feed