When Hildegard was 43 she had a vision of a brilliant light accompanied by intense pain. She saw a shimmering aura that she Called the living Light that instructed her to speak and write about her visions.

“Oh mortal, who receives these things not in the turbulence of deception but in the purity of simplicity for making plain the things that are hidden,” the Holy One said that day in 1141, “write what you see and hear.”

This presented Hildegard with a dilemma. As a woman she was considered ill educated, she had no authority to write on theological matters and as a female her views would be discounted anyway. She wrestled with self doubt and pleaded with God to be allowed to be carried by him 'like a feather on the breath of God' . So realising that her only recourse was a direct appeal to God as her authority, she spoke with her confessor, a monk called Volmar. He promptly spoke, with his Abbot, who approached the Archbishop of Mainz, who spoke to the Pope and quite swiftly authority was given for her to write. Volmar was instructed to help her and Hildegard dictated to him, and he gave her sentences the necessary grammatical smoothness without detracting from the vibrancy of her words. For if there is a single word to summarise Hildegard's writing it is 'veriditas' or 'greenness', the word that she uses to describe the action of God in everything, from creation to the human soul. In order to grasp the power of this word we need to imagine the world of the Middle Ages, especially the monastic world, in which there was very little colour compared with the technicolor world in which we live. There were no plastics or synthetic dyes. Most things were of an earthy hue, or perhaps black. Without bleach even whites tended to be off white. In this world the brilliance of church vestments or even an illuminated page of a manuscript really stood out, and when after winter the first green shoots of Spring began to emerge from the thick snow that greenness shone out, throbbing with the promise of new life. This is what Hildegard mean by Veriditas, and she applies it to everything.

In Symphonia she wrote:

“O most noble greenness

Rooted in the sun,

you who emanate light in

peaceful white rays

from the center of a wheel,

a wheel no earthly mind can comprehend,

you are enfolded by the embraces of the divine mysteries.

You glow like the dawn.

You burn as flames of the sun.”

“Divine Love, the heart

of hearts, abounds

in every grain of being,

from atom’s gleam

to starry sky, from darkest

pain to brightest joy.

Unceasing love kindles life--

a royal promise sealed

with the kiss of peace.

I gleam in the waters, and I burn in the sun, the moon and the stars. With every breeze, as with the invisible life that contains everything, I awaken everything to life."

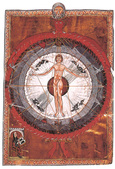

Hildegard's first books, her so called Scivias , meaning Know the Ways, were theological and ethical, though the last of these was perhaps more scientific. She also produced a morality play, many works of medicine and even a hidden language of 900 words, perhaps created to bond her sisters, or just for fun. She was most interested in the workings of the human body, and unafraid to venture in areas of gynaecology and sexuality unusual for her day. For her everything was inter related and the human body was seen as a microcosm of the divine body that interpenetrates the universe. In her book Causes and Cures she wrote:

“Fire, air, water, and earth are in humankind and humans consist of them.

From fire they have the warmth of their bodies, from air they have their breath, from water they have their blood, and from earth their bodies.

They can thank fire for their sight, air for their hearing, water for movement, and earth for their ability to walk."

Just to give us a taste of her insights and her remarkable musical work, we will hear now her composition O Quam Mirabilis, whose words in English read: 'Oh how marvelous is the knowledge of the divine heart that fore knew every creature. For when God gazed into the face of the human being whom he formed, he beheld all his works whole in that same human form. O how marvellous is the inspiration of God that rouses humans to life.'

So popular were Hildegard's writings that soon many more women were seeking to join her group of sisters and more space was needed. She identified some land at nearby Rupertsburg and declared her intention of building a convent there. The abbot of Disibodenburg was not happy about this, as it meant less prestige for his monastery. However Hildegard promptly fell sick with an apparently deadly illness, and faced with her imminent demise he gave in. Hildegard immediately recovered and worked hard to build a wonderful facility, with gracious rooms, running indoor water and large medicinal herbal gardens. It was like a second birth for her almost literally. In those times 40 was the average lifespan. Hildegard would go on to live to the age of 81, passing on her wisdom to her young sisters and providing them with a spacious learning environment in which the arts could flourish. Her counsel was sought by kings, bishops and abbots and the learning of her convent was renowned.

What is her legacy to us? Certainly she was someone who knew how to act upon her own inner authority and to give priority to the insights of prayer. She was also someone who recognised the inter relationship of all things. So as we celebrate her, we may want to question ourselves about the things we really know in our hearts but lack the courage to act upon. What are the things we need to proclaim to our own age by our example as much as by our words? Certainly some of H's message of care for living things resonates with our own more modern understanding, that we need to live more simply, less violently and more in harmony with the natural order.

We are beginning a little better to recognise the harmony of mind, body and spirit by which Hildegard lived and healed. She describes how God has mounted a sensitive gauge inside each human body, that tells us exactly what we need - how much food, exercise, warmth etc. She was an early proponent of the view that it is critically important that we listen to our body as the means of listening also to our soul. If we listen correctly to our body we will not lack or take in too much - a great lesson for the West in these days of over consumption and surfeit.

Hildegard also left us a priceless treasure of music to keep our yearning for paradise alive. She saw music as a way of re ordering the universe and bringing it back into the original harmony of the garden of Eden. This is why in her morality play the only character that does not sing is the devil. At the same time, and despite her own prodigious output, Hildegard recognised the inadequacy of anything we may try to say about God. She wrote:

“Not a single spark of any creature’s understanding can grasp the ungraspable God. You can only fall at his invisible feet and, finding no ground there, finally fly."

For Hildegard everything is aflame with the glory of God, and from that glory flows love, life and peace. She wrote:

“Divine Love, the heart of hearts, abounds in every grain of being, from atom’s gleam to starry sky, from darkest pain to brightest joy Unceasing love kindles life—a royal promise sealed with the kiss of peace.

Hildegard's biographer Mirabai Starr offers a beautiful prayer which I offer to you in conclusion, before we hear some of Hildegard's composition, Ignis Spiritus, fire of the comforting spirit. Let us pray:

“O God,

by whose grace your servant Hildegard,

kindled with the fire of your love,

became a burning and shining light

in your House:

Grant that I may also be aflame

with the spirit of love and devotion,

and walk before you as a child of light.

O Sophia,

Spirit of Wisdom,

who speaks the language of God in our hearts,

speak to me now;

And infuse me with the courage to listen.

Amen."

Penny Jones for 'Voices of Faith', at Evensong in St John's Cathedral Brisbane, Sunday 4 September 2016

RSS Feed

RSS Feed