In a real sense therefore, we are what we are in this particular space, partly because of John Keble and his colleagues. If it was not a revolution, it was, to use a Russian phrase, a perestroika, a major restructuring, assisting the church’s transformation in the face of a fast changing modern world. So, in this, in Keble, can we perhaps find fresh inspiration for the similar, though different, challenges of our identity and mission today?

The Assizes Sermon itself took place in St Mary the Virgin, the University Church on High Street in the Oxford: which was, as it happens, my main Church when I was a history student studying my first degree. As a nineteenth century sermon, it does not set the heart alight today, yet its central message remains: what will we, as a Church together, do in the face of what Keble then called ‘National Apostasy’? What Keble was talking about were shifts in society: particularly the changes made by Parliament to reorganise the Church of England and religious life in general. The Catholic Emancipation Act had also been passed in 1829 and other prohibitions lifted on nonconformists. Meanwhile the passing of the Great Reform Act of 1832 not only marked the beginnings of a more democratic age but was accompanied by other new movements, some of which came into aggressive conflict with the Church in some places. Will the Church, Keble was asking, simply go along with what happens to it and to changes in society? Or will it reclaim its eternal foundation and speak freely into the new world that is emerging?

What does John Keble offer us today, in the face of similar questions? Four things, I believe, embodied in his person, each of which begins with the letter ‘p’. Let me touch on them briefly.

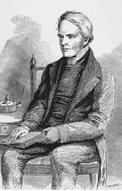

Firstly, Keble was a prophet and thus still calls the Church to be prophetic. In hindsight there are some reactionary elements to his thinking. We had to wait, for example, for other Anglican prophets like F.D Maurice, and for later generations of more liberal Anglo Catholics, to come to terms with biblical criticism and what is good and vital in the impulses of liberalism and socialism. Yet Keble’s teaching vitally brought the Church, as a body, back to its true ecclesial identity. For the Church is not to be a mere department of government which simply sacralises the values of any society. Rather it is an eternal sacrament of the ever-transforming love of God which relativises every political and social order. And when the values of God are betrayed we need this reminder. Evangelicalism (with its arguably deficiencies in ecclesiology and incarnation), and Broad Church reason and generosity (which arguably are tempted to fall into Erastianism), are not enough.

Secondly, Keble was a professor and thus continues to calls us into an ever deeper search for truth. He was personally outstanding: being only the second person to receive a double first at Oxford and then becoming a highly regarded don. A vibrant Anglican identity, he reminds us, is strongly founded on the very best study and insight we can pursue.

Thirdly, Keble was a poet, like so many of the really foundational figures in our Anglican tradition: a reminder that fresh spiritual life is a creative discipline which always seeks new artistic expression. His most notable work was that entitled The Christian Year, comprising around 100 poems for the liturgical cycle, published in 1827 and the most popular English book of religious poems in 19th century. For the poetic spirit of Anglicanism is at its heart and it is arguably this and its liturgical embodiment in The Christian Year that most helped the Oxford Movement to thrive: arguably even more than Newman's illuminating theology or Pusey's brilliant organisation.

For fourthly, and most importantly, Keble was a priest. This was his deepest vocation, and, from 1836, he spent thirty years as incumbent of Hursley, near Winchester. Yes: informed prophetic challenge, professorial depth, and poetic spirit, are all vital for us to cultivate together. Yet there is something more: embodied spiritual formation and commitment. Ultimately this service of prayerful love is the key to a healthy and vibrant Anglicanism, even when the odds are against us. In the face of opposition, and when friends like Newman left the Church of England for other places, Keble simply kept on praying and loving. ‘Truth is ever unpopular’, he said, and ‘if the Church of England were to fail, it should still be found in my parish’. Those who have ears to hear let them hear.

Soon after Keble’s death, a college was built in Oxford in his memory, so highly regarded as he was. So what is our memorial today? In what ways are we, each and together, called to be prophets in our contexts, professors and scholars of truth, poets and artists of the soul, and priestly people lovingly engaged with the humblest as well as the highest aspects of our lives and world? For we too live in watershed times in which the Church needs reconstructing. On what foundations will we build, and how we will live out our faith?

In the spirit of Keble let us conclude, and sum up, with his hymn New Every Morning, from his poem in The Christian Year. For it reflects his spirituality - incarnational and humble, but alive with the awareness of God’s glory, seeing and finding God in 'the trivial round' as part of the one, holy, catholic, and apostolic Church.

New every morning is the love

our wakening and uprising prove;

through sleep and darkness safely brought,

restored to life and power and thought.

New mercies, each returning day,

hover around us while we pray;

new perils past, new sins forgiven,

new thoughts of God, new hopes of heaven.

If on our daily course our mind

be set to hallow all we find,

new treasures still, of countless price,

God will provide for sacrifice.

Old friends, old scenes, will lovelier be,

as more of heaven in each we see;

some softening gleam of love and prayer

shall dawn on every cross and care.

The trivial round, the common task,

will furnish all we ought to ask:

room to deny ourselves; a road

to bring us daily nearer God.

Only, O Lord, in thy dear love,

fit us for perfect rest above;

and help us, this and every day,

to live more nearly as we pray.

In the name of Jesus Christ, Amen.

by Jo Inkpin, for John Keble's day in the Australian Anglican lectionary, 29 March 2017,

preached in the Chapel of the Holy Spirit, for the Anglican Parish of Auchenflower-Milton and St Francis College

RSS Feed

RSS Feed