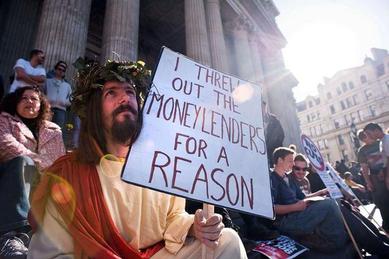

There are, sadly, many reasons why I dislike the current owner of Newcastle United Football Club. Sometimes it seems as if he deliberately seeks to offend. Maybe it is too easy. After all, Newcastle United fans are among the most passionate you will ever find. We tend to wear out hearts on our sleeves and, consequently, we suffer the consequences when we are abused. Of everything Mike Ashley has done however, the most offensive, for me, is the selling of of the Newcastle shirt. For Wonga, the main sponsor’s name on the shirt, is the name of a British payday loan company: a moneylender, which, to be quite blunt, rips off the poor. Wonga has thus often wreaked havoc in the lives of many people in Newcastle upon Tyne and its surrounding area, the poorest region of England. As a ‘short-term, high-cost credit’ moneylender, Wonga indeed quickly became a by-word for exploitation. Its interest charged can sometimes equate to an annual percentage rate of more than 5000%. For this reason, not for nothing did the Archbishop of Canterbury not so long ago launch an Anglican campaign against such moneylenders, offering Church of England facilities to community-organised credit unions as a constructive alternative. In doing so, Justin Welby was following the example of Jesus, and, arguably, though perhaps surprisingly to some, embodying the parable we have just heard. For he was addressing the great, usually forgotten, sin of usury: a vital issue for us all, not least at this time of the G20 meeting in Brisbane…

One of the difficulties we can have with today’s Gospel reading is that it talks about the word ‘talents’. Immediately we therefore think about talents in the modern sense of the ‘gifts’ we possess. At once, we begin spiritualising the parable. What however if we stick with the original meaning of the word ‘talent’: namely, in Jesus’ day, a unit of currency, worth about 6 000 denarii? Now one denarius alone was the usual payment for a day’s labour. This means that, in Jesus’ day, one talent alone was worth about what a labourer would take twenty years to earn: maybe somewhere up to even a million dollars. What Jesus is talking about therefore are immense amounts of money. Is he then making a comment, and none too subtle, about the economic system of his day? After all, let’s remember, in Matthew’s Gospel, the very first thing Jesus does after he enters Jerusalem is drive the moneymen out of the temple. As he comes to the end of his time of conflict in Jerusalem, may it not be that he is returning to this same theme?

When the owner of Newcastle United chose to sell the people’s shirt to Wonga, the moneylender, he met opposition from some typical quarters, and from religious ones he was not expecting. Not least, as well as the Archbishop of Canterbury, he met vocal Islamic opposition, including from those of his own footballers who are Muslim. For Islam is strongly opposed to usury, the charging of interest in loans. Nor is it alone. In fact, for about three quarters of Christian history, the Church was similarly strongly opposed. For usury is explicitly condemned in the Bible, again and again: in Exodus, Leviticus, Deuteronomy, Nehemiah, the Psalms, Proverbs, Isaiah, Jeremiah, Ezekiel, and in the New Testament.

Take another look at today’s Gospel reading. We often tend to assume that the man with the money who goes away is like God. Yet is he? The great lord in this parable is said to be a ‘harsh’ man, who reaps where he does not sow, and gathers where he does not sow seed. Is this really a picture of God: a picture, for example, of Jesus? Hardly. Crucially, Jesus also quotes the ludicrously rich man’s response to the servant who hides his one talent in the ground: ‘you ought’, Jesus has the man saying, ‘to have invested my money with the bankers, and on my return I would have received what was my own with interest.’ In other words, the rich man in the parable is saying precisely the opposite to what the (Hebrew) Scriptures have said again and again. Is it not more likely therefore that Jesus was actually telling this story to expose the economic corruption of his day and the exploitation of the poor? What a difference is made by seeing this! We have often thought that the man who buried the talent was a bad model for godly living. Yet for Jesus’ first hearers he would actually have been the hero: the one man who refused to carry on exploiting the poor, making more money by financial speculation. This is metaphorical dynamite! As he did in driving out the money men from the temple, Jesus is taking on the kind of economics which make the rich richer and keep the poor in poverty and dependence. This is not good news. No wonder that the rich and the powerful very soon had Jesus arrested and crucified. That is typically what happens when anyone rocks the boat of the rich and powerful, isn’t it?!

I wonder therefore, armed by this parable, what Christians should say to the very rich and powerful people gathering in Brisbane for the G20 Summit this week. What do you think? What I do know is that Jesus must be pleased with Christian leaders, like the Archbishop of Canterbury, and Pope Francis, who have spoken out against systematic economic exploitation. As with some other biblical prohibitions, both the Anglican Church (from Henry VIII onwards) and the Roman Church have developed their outlooks. Today we recognise that our context has changed and that, in a large, complex, international society, there is a place for certain kinds of loans, interest and money use. To some extent, even in so-called 'communist' China, it is true to say that 'we are all capitalists today'. Yet this does not mean that anything goes. Rather, as Pope Francis fiercely observed in his first major address on the global financial and economic crisis, Christians are called to challenge the ‘cult of money’ and the ‘tyranny’ of unbridled capitalism.

Let me conclude with some words from John Milton, one of the greatest of all writers, and proponents of liberty, in the English language. Milton was fascinated by the Parable of the Talents and referred to it frequently, not least in one of his best known sonnets, entitled On His Blindness. This refers to God’s reaction to the use of Milton’s own perceived lack of use of his ‘one Talent’. As he put it:

When I consider how my light is spent

Ere half my days, in this dark world and wide,

And that one Talent, which is death to hide,

Lodg'd with me useless, though my Soul more bent

To serve therewith my Maker, and present

My true account, lest he, returning, chide

"Doth God exact day-labour, light denied?

I fondly ask. But Patience, to prevent

That murmur, soon replies: "God doth not need

Either man's work or his own gifts: who best

Bear his mild yoke, they serve him best. His state

Is kingly; thousands at his bidding speed

And post o'er land and ocean without rest:

They also serve who only stand and wait.

‘They also serve who only stand and wait’: what Milton is saying is that we must not fall into the trap of thinking that making money, or doing anything else for God, is somehow necessary to serve God. Rather, God is really not interested in our ‘work ethic’. What matters is whether we know and share his love. God, for Milton, is not the lord of Jesus’ parable. For God is interested in is love and justice and mercy for all, not success for a few. Sometimes we need to resist the siren call to produce and achieve more, so that we can hear again the voice of God, so that such justice and mercy can be known by all. In the name of Jesus who resisted the moneylenders, Amen.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed