We know Mary of course first as mother – the mother of Jesus; the ‘theotokos’, the ‘God-bearer’ as the Orthodox describe her. She was a mother who knew what it was to be an outcast, a refugee, a person for whom there was ‘no place’, either physically or culturally. And in our hearts just now are so many mothers with ‘no place’. We think of the mother who gave birth in the labour ward of the St George hospital in Beirut during the blast - her ‘safe place’ taken from her in twenty seconds. We think of Pamela Zeinon, the nurse who rescued three new borns from their incubators, who said in an interview that as she carried them for hours through the rubble that she was sustained by the sense that she was for that time their mother. And during this pandemic we think of the mothers seeking to shield themselves and their babies from harm. The courage and the resilience of Mary is an example and a resource for them.

There have been in Christian history some very saccharine and some very divinised versions of Mary that make of her an image of unattainable perfection. Yet the Mary that can help us in these difficult days is mortal. She takes her new born child and wraps him in bands of cloth, to protect him from the elements, just as Pamela Zeinon took whatever clothing she could find from passers-by to wrap those newborns and protect them. It’s fragile isn’t it, a band of cloth? – so little and yet so much. The difference perhaps between life and death – warmth and protection for a baby at risk; or for us perhaps a mask, a band of cloth, the difference between deadly infection and life. Mary was mortal and she knew the fragility of life. She knew that one day her son’s dead body too would be wrapped in linen cloths, even as today so many bodies around our world are wrapped.

Her mortality and her courage in the face of that mortality gives us strength and hope as we face our own. Yet Mary was more than mother and mortal. She was the dynamic beginner of the Jesus movement – a movement summed up in the song that Luke gives her, that we shall sing at the end of our service today, the Magnificat – ‘my soul magnifies the lord’. Mary’s life shows us how to magnify, how to make God bigger in the world. It gives us an example of how to work with God’s spirit of liberation – the movement that overthrows the rich and the powerful and raises up the poor and those who have no voice.

The baby laid tenderly in the manger by his mother will go on to overturn the world not just the money changers’ tables. Where did he learn that? Surely at his mother’s knee. Who better then to help us as we cry out for justice in our day, through our support for #BlackLivesMatter, or Fair Trade Fortnight, or climate justice or LGBTIAQ+ rights or any movement in our world for equality and justice – who better to take as our mentor and guide than Mary? Mary who gave birth to her son in a drafty barn, all control taken from her by the imperial power of Rome who directed its citizens to be registered. Who better than Mary, whose son would be crucified by those same imperial powers in the attempt to change the world? Mary, who as mother and mortal knows our pain and our struggle and inspires us nevertheless to speak and act for the most vulnerable.

Mary - mother, mortal, magnifier - teach us to follow in the steps of the son you bore, raised, buried and glorified, Jesus – in whose name. Amen.

by Penny Jones, for the Feast of Mary the Mother of God

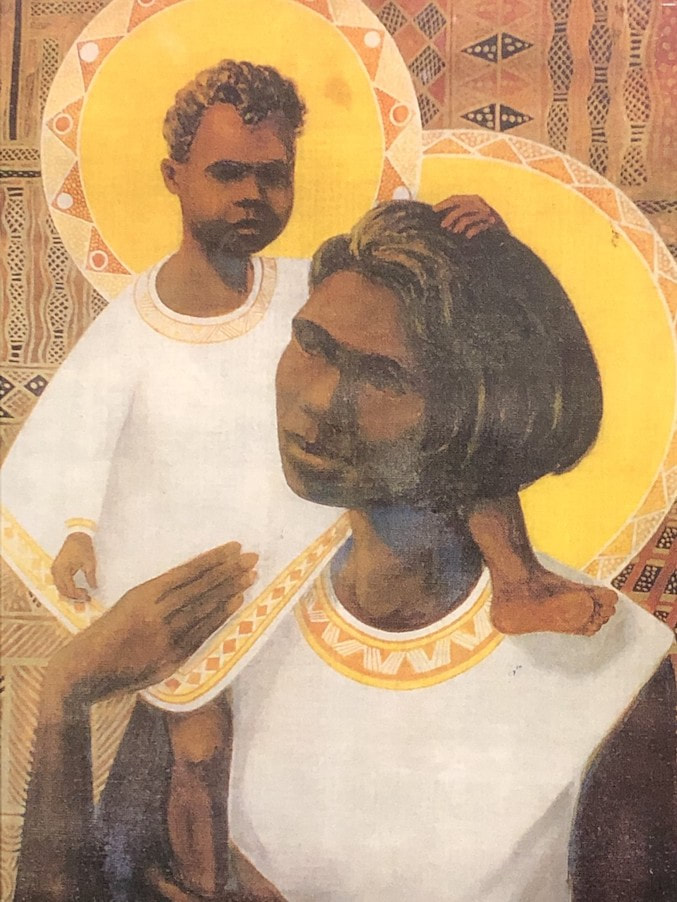

photo: from a copy of the ‘Madonna of the Aborigines’, commissioned by Bishop John Patrick O’Laughlin, who built St Mary’s Star of the Sea Cathedral in Darwin. Karel Kupka, a Czech artist, known to the bishop was invited to paint this image and it shows the Madonna carrying her son on her shoulders, in the fashion of Aboriginal women from the Tiwi Islands and the Daly River, with one of her hands clasping the baby by the ankle and the other resting gently on his hip.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed