"When Jesus saw her weeping, and the Jews who came with her also weeping, he was greatly disturbed in spirit and deeply moved."

We are missing something in this translation. The New English Bible is probably closest to the original Greek in offering, "Jesus was moved with indignation and greatly distressed" but it still does not convey the full impact of the original. Two words describe Jesus's emotional engagement

when he sees the weeping of Mary and the crowd of official Jewish mourners who surround her. The first means literally 'to be moved with anger', or 'to admonish sternly', and also to 'snort like a horse'. Mark's gospel uses the same word in the story of the woman who anoints Jesus, to describe the reaction of hue he disciples to her wastefulness - 'they scolded her, or admonished her sternly'. We tend to assume that confronted by the outward display of grief by Mary, Martha and the crowd,

Jesus empathises and joins in with their behaviour. But in fact the Greek is saying something else. It is saying that his responses included indignation and perplexity. For the second word - ταρασσω - translated in our version as 'greatly moved' means to 'stir up' (like the waters of the pool of

Bethsaida ) and in the case of a person to be churned up, troubled or perplexed.

So why is Jesus indignant - even angry - and perplexed? ...

Again it helps to realise that two different Greek words are being translated by the same English word, 'weep'. The first, κλαίω which John applies to the mourning party, really means to 'wail'- to mourn in a highly ritualised, cultic way. The word that is used for Jesus's own weeping on the other hand, δακρυω, is a much more personal word for the shedding of tears quietly - and it is used only here in the whole New Testament . All of which suggests that Jesus is not at all impressed by the outward trappings of cultic grief - the weeping and wailing and carrying on, indeed he snorts with indignation! - and his own tears are for something more than the anticipated death of his friend.

The Biblical scholar Gil Baillie offers this persuasive argument, "this crowd is going through the customary ritual wailing, and Jesus is angry about the grip that death has on these people, even Mary and Martha. Ritual mourning is a cult event, a mass behaviour that creates communal solidarity. The weeping and wailing that accompanies such cultic events exploits a natural death for its cathartic, tribal bonding potential - there's nothing like catharsis to galvanise a crowd! This rests

on a certain fascination with death, and a communal unanimity against a perceived enemy which such fascination generates." All this is immediately recognisable in our culture also - think of the powerful attraction of our Anzac Day ceremonies for example!

The truth is that death is very, very seductive. After all we know what to do with the dead - bury them, celebrate their achievements , preferably ignore their shortcomings, lament together and feel united in our grief. But this sacralising, this making holy of death, is deeply unhealthy. It does not encourage us towards the much more important, but much more difficult task of living; of engaging with others whose views do not match our own; of grappling with relationships that are complex and demanding; of daring to let go of behaviours and ways of being that are crippling and destructive. Jesus snorts with indignation at the grip that the death cult has, even over those who know him best, his dearest friends, who have the clearest perception of anyone in the gospels of who he really is. Even Martha who knows that the dead will rise, even Mary who will anoint him, even they are in thrall to death - in other words, it happens to the best of us, the best clergy, the best parish, the most devoted disciple. No wonder Jesus weeps!

"I am the resurrection and the life", Jesus tells Martha, yet she carries on weeping and wailing with her sister Mary and the crowd. The whole 'good news' of the resurrection is that we are no longer enslaved by death. Of course, of course, letting go of those we love is painful, and of course Jesus is with us in the pain of bereavement and in any suffering that is real. What He is indignant about is the mis -use, the abuse, of the emotions surrounding death, to keep us captive to death, and unable to move forward.

The gospel is always always about life and transformation. And we can see this in the very purposeful commands that Jesus goes on to give in this story. These are the commands that lead to life. They are commands that we do well to ponder deeply in our lives as individuals, as parish and in the wider world and church. "Take away the stone" - in other words, move the blockages, the artificial barriers that we have erected. To do so requires strength - physical, but also often emotional and spiritual, for the very reason that Martha gives, "lord already there is a stench because he has been dead four days." Uncovering the dead, whether the dead parts of ourselves, or our life together in community can

cause a bit of a stink to say the least. It is often not pleasant to be forced to acknowledge the things we have kept walled up for four days or four years or four decades or more. But until we take away the stone, no new life can begin.

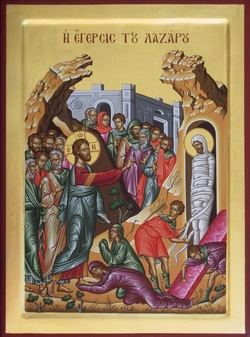

"Lazarus come out" - Jesus commands. Are we too bold enough to call forth the long dead and forgotten parts of ourselves, our church, our world? - the unfulfilled potential, the buried dreams, the lost vision? Are we prepared to bring them in all their fragility and woundedness to the light of day, where healing and hope happen? They may be unrecognisable horrific even- like Lazarus, this resuscitated corpse, shuffling forward, his hands and feet bound and his face wrapped in cloth, like something from a hammer horror movie. Do we have the courage for this? - or would we rather stay safely locked in the tomb of our fears and disappointments?

Jesus said to them, "unbind him and let him go". Notice how resurrection is always a communal matter not just an individual matter. We cannot free ourselves, by ourselves - even with God, we need each other in community, gently to release, to untie, to bring back the circulation, the flow of life blood.

So over these next two weeks as we prepare for Easter, I invite you to reflect prayerfully on the things in your own life, and in the life of our church and world which we have allowed to be seduced by death; the things that we do only because they have always been so, and not out of any fresh, daily encounter; the things that have ossified into habit. Ask what needs to be allowed to die, that new life may come; and what needs to be called forth from the tomb, unbound and let go. And don't be afraid of the stink. For as the writer Margaret Silf puts it, "if we remain in denial and put the patient on life support, we will miss the point. We will be denying Calvary and blocking resurrection. New life is always preceded by dying. It was true of the stars and galaxies, and it is true for our systems and institutions. The gap between the dying and the transcending is terrifying - that is why Jesus walked it before us, and walks it with us. This dying asks that we cross the bridge of trust, letting go of the past with love, and reaching out in hope to all that calls us forward." Amen

RSS Feed

RSS Feed