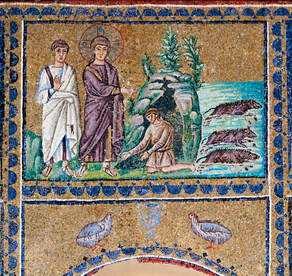

feature from Sant'Apollinare Nuovo, Ravenna

feature from Sant'Apollinare Nuovo, Ravenna This is a story where the gap between our current lived experience, and the lived experience of first century Christianity, is frankly enormous. The whole scene as Luke describes it is ‘queer’ – in the sense of ‘not-fitting with our expectations’; in the sense of lying outside certain normative parameters. An artist’s impression would give us something between a hammer horror movie and a political cartoon.

There’s this naked person, perceived by others at least not to be in their right mind, coming out from some tombs in the middle of the night; there are chatty demons, pigs throwing themselves off cliffs and a small riot of freaked out locals. So how are we to read it?

different readings

We could try to read it literally – but that would mean not only accepting an idea of demon-possession, but that Jesus was happy to kill a lot of pigs – whatever happened to that nice guy who encouraged us to think that God cares even about the sparrows? And what kind of magical transference puts demons into pigs anyway? So literal is not going to work for most of us.

We could try for a critical, reductionist reading, exercising a suitable hermeneutic of suspicion. We could posit for example that this story deals with first century understandings and misunderstandings of mental health, and a coincidental stampede of pigs. We could even suggest some kind of socio-political critique of Jews keeping (or being forced by economics to keep) pigs, which makes them ‘sick’ in the moral sense – and getting rid of the pigs, therefore makes them better.

There is certainly mileage in that trajectory. It is very reasonable to ask why Judaeans are keeping pigs, thus making themselves constantly ritually impure and unable to approach God. Poverty would seem to be the likely cause, and when the supposed ‘demons’ give their name as ‘legion’, the legions of Roman occupying forces, bullying locals and diminishing their ability to make a living, come easily to mind.

Fascinating – but from our perspective – the perspective of those coming to the gospel on this 45th anniversary of our church, seeking reasons perhaps to continue in faith our journey of discipleship – I would suggest, not enough. What is there in this text – strange as it is – that can nourish us, and give us wisdom and guidance for our own journey, our own story?

Let’s start to read it from Marcus Borg’s perspective of a post -critical naivete – to read it just as a story, that can help us. We come to the story perhaps with the question, how can we in our own times be ‘like Jesus’? We don’t want to be Jesus, but to do what they did – which was to be totally and authentically themselves, right to the end. Jesus was the best Jesus ever – and we aim to be the best Penny, Jo, Kent, Dawn, whoever, ever. So how?

We could try seeing where we might locate ourselves in the story. Do we see ourselves as most like Jesus, or more like the naked person, alone, afraid and desperate? Do we feel ourselves perhaps with the disciples, who as far as we can tell perhaps wisely, never left the boat? Within the story they seem to offer some kind of ‘get-away’ vehicle. Or are we finding ourselves perhaps disconcertingly resonating with the angry townsfolk, whose livelihood has fallen off a cliff - as of course have so many businesses even in ‘lucky’ Australia, in recent COVID times, and in the wake of fire, flood and war. Where we are in the story, may determine how we receive it.

what about Jesus?

But let’s suppose that we identify with Jesus at least as exemplar. What does this story show Jesus doing? Firstly, it shows Jesus approaching the other with openness. We’re told that as Jesus ‘stepped out on shore’, the man comes to him. In other words, Jesus has had hardly any time to adjust to his new environment before he encounters the challenge of this very difficult character. We might want to think about how things are for Jesus at that moment. Why for a start is he in the country of the Gerasenes? That is the territory of the so called Decapolis, the ten towns, Gentile and Roman territory. Not a place any respectable Judaean would choose to be. So why is Jesus there? Possibly because a few verses earlier Jesus was very tired, he fell asleep in the back of the boat and woke up to find there was a big storm raging and he was being asked to sort all that out. So maybe this is a case of ‘any port in a storm’ – crisis passed, the disciples have pulled the boat in to do some running repairs – perhaps. At any rate it seems likely that Jesus is pretty wrecked, if you’ll pardon the pun, and just getting his legs back on dry land when this somewhat interesting character turns up – and quite honestly we could have all have forgiven him, if he’d said ‘sorry mate, just not - now…’

But it’s Jesus, so he doesn’t. Rather he remains open to the other. Now it’s not easy to be open to the other when you’re exhausted, just got off the boat, it’s hardly light in a strange place and you don’t really know what’s going on. These are circumstances in which it would be easy to make a mistake about what you’re seeing. And I think Jesus does make – if not exactly a mistake – certainly a miscalculation. For the text says that Jesus commanded the unclean spirit – singular – to come out of him. He could see that the man was very troubled and he did the first thing he knew how to do to relieve that trouble.

naming suffering in openness to the other

This is helpful to us because it is what we have to do as well. Seeking to be open to the other – however strange and troubling they may be, we must seek to relieve immediate and obvious suffering. So in our context that may mean for example sending money to provide for the refugees from Ukraine; or sending blankets and boots to help those trying to stay warm in Lismore after the floods. It’s an immediate, compassionate response – the kind of response that we would expect from churches no matter their age or ethos.

It’s good – but it will rarely be enough, and it is not enough in this case. As Jesus head clears, as he begins to look around him and take in the context – tombs, cliff, pigs, - Jesus realises that they need more information. He asks, “What is your name?”.

Such an important question. If we were reading the story in a literal way, we would understand that the giving of a name allows an exorcist power to cast out an evil spirit – or in this case thousands of spirits. But reading it from our own twenty-first century post-critical position, the question remains a powerful one. It is a question with the power to take us beyond an open compassion, to a core value of the Uniting Church – to justice, if we have the courage to embrace it. For when we begin to look, with compassionate contemplative openness at some of the truly terrible, frightening and dehumanising (and the man in this story has for whatever reasons been utterly dehumanised) situations in our world, we encounter the same multiplicity that Jesus did.

For instance, if we try to help one starving child in our world today, we quickly discover that the child is not just confronting the ‘demon’ of hunger. They are bound by other and more intractable demons – the demons of powerlessness, disease, war, greed, political apathy and manipulation, inequality, tribal hatreds, persecution of minorities – and on and on. The better we understand the chains that seek to bind, dehumanise and conform that child to norms that include the privileging of some other others, the more accurately we can name the ‘legion’, the modern time demons that keep that one child bound to starvation. Compassion leads us to feed that child. Justice demands that we put ourselves at risk to speak out and to change the structures of power and control that keep them and thousands like them in that place.

asking important questions

So, like Jesus, we need to ensure that we are not only open to the other, but also willing to ask important questions – the unpopular questions that enable us to identify the demons, wherever they are to be found, in governments and institutions of all kinds, including no doubt our beloved Uniting Church. For forty-five years the UCA has worked tirelessly for justice in many arenas, and we rightly celebrate that today. But we cannot afford to presume that the demons of racism, sexism, homophobia, transphobia and many other systems that work to exclude from our ‘norms’ those who are different are not at work among us.

So, what next? The first step for Jesus and for us is to offer openness and a compassionate response. The second is to ask questions and identify clearly by name the ‘demons’ at work. But then there has to be an element of ‘letting go’ – we get a hint of this in Jesus giving permission to the demons to enter the swine. Once something is seen for what it truly is, it is no longer so fearful – it does not hold us. We can in some sense ‘come out’ and be ourselves. And there’s an element almost of spiritual discipline about then letting it go – not seeking to take back and control or letting ourselves be overwhelmed by the enormity of whatever oppresses us but having the courage and the faith to let it go.

where now?

The person in this story who is made well wants to stay with Jesus. This is understandable. He does not trust that the change will be permanent. He does not trust that the hostile townsfolk will not blame him for the loss of the pigs and try to tie him up again. But Jesus obliges him to stay in his own place – to face down those who have bullied and belittled and declare the liberating action of God.

This story today may seem at first glance remote from our every day experience. Yet none of us is a stranger to the demons of othering, of social, economic and political oppression. And this queer tale gives us tools to carry forward not only our individual journey of discipleship, but the charism of the church of which we are apart – a charism that reaches beyond compassion to justice. It is a story that invites us to respond to the call to approach others with openness; to ask the difficult and revealing questions and to seek ways forward that liberate ourselves and others.

So on this anniversary day, may we commit ourselves afresh to this way of living, and with praise on our lips and in our hearts may we like the Gerasene, declare how much God has done for us. Amen.

by Penny Jones, for Sunday 19 June 2022, Pitt Street Uniting Church

RSS Feed

RSS Feed