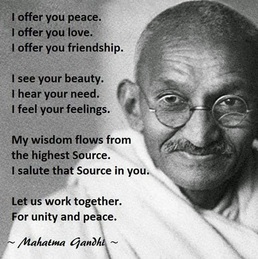

Most of have probably heard of Mahatma Gandhi. What however does ‘Mahatma’ mean? It was not the real name of the remarkable 20th century Indian leader called Gandhi. His name was Mohandas Karamchand Gandhi. The honorary name Mahatma was given to him because of his amazing character. Indeed, it was given to him when he was a lawyer in South Africa, especially for his deep concern and work for the poor. For the name Mahatma comes from a Sanskrit word which means ‘high (or great) soul’. In Christian terms, we might say ‘saint’, or, simply, one who is ‘great hearted’.

Whom would you name Mahatma today?

Whom do you see as ‘great hearted’?...

Today’s first reading tells us about a Mahatma. Again, she was not a Christian as such, and not even a Hebrew, a member of the people of ancient Israel. She was in fact a member of the race who were oppressing the people of Israel. She was an Egyptian. More than that she was a member of the royal house of Egypt. She was indeed the great Pharaoh’s own daughter. Yet, when the great Pharaoh, her own father, commanded that all Hebrew boys were to be thrown into the river Nile and drowned, what did Pharaoh’s daughter do? When she saw the baby boy hidden in the reeds, she saved him. She raised as her own. She made him her own son, calling him Moses, who was to become the saviour of the people of Israel. Actually, the whole story we hear today involves great heartedness by many women, not least the midwives of Egypt. They wonderfully resist Pharaoh's decree to kill Hebrew boys at birth, persuading him that Hebrew women somehow produced babies too quick for them to respond. Pharaoh, clearly a powerful man who knows and cares little about childbirth, is outwitted. Not for the first, or last, time in history, god-fearing women, though largely subjugated, find ways to resist powerful forces.

The title Mahatma, a great hearted person, certainly then fits the Pharaoh’s daughter, and the midwives, doesn’t it? It also fits anyone whose heart contains mercy and love for others, from whatever race, or religion, or creed, or background, they come. It fits the Canaanite woman we heard about in our Gospel reading last week. It fits the Christians who protect Muslims in some places where they are threatened by others. It fits the Muslims who in some places protect Christians when they are threatened. It fits anyone who shares in the great compassion, the great heartedness of God. This is what part of what it means truly to follow Jesus.

One of the great Christian writers of our time, the American Benedictine Sister Joan Chittister puts it like this:

The person who learns to pray with the heart of God, she says,

has no patience for injustice anywhere. They see with the prophet’s eye. They break down national boundaries. They transcend gender roles. They have no sense of colour or caste, of wealthy or poor. They see only humanity in all its glory, all its pain.

It is a timely message for our current world: a message which the story of the Pharaoh’s daughter has for us today. For:

The person of prayer is not a person of private agendas. The more we become like God, the greater-hearted we become as well. We have no sense anymore of “we and they” or “them and us” or “me and mine.” Now our hearts open to take in the heart of the world. When, in prayer, we come to discover God’s universal love we suddenly realise that God does not take sides, that we have no priority on God alone. We finally understand that the God we seek is the God of the world and so, to seek that God, we must develop hearts as big as the world ourselves.

Then, as the Pharaoh’s daughter showed us, in rescuing a little boy from another nation:

Then, racism makes no sense and sexism is as much a sin as any other kind of discrimination, and war is blasphemy against humanity. Then we become bigger than our single nation… truly universal—in our cares and beliefs and commitments.

To develop a cosmic heart is a moment of profound transformation. We can never be the same again. We are beyond the boundaries we have created to separate the human race into my race and theirs. Then prayer becomes truly co-creative.

Otherwise prayer is nothing more than some kind of spiritual spa designed to make me feel good. It is reduced to an exercise the intent of which is to assure me of my own value. It swaddles me in self-righteousness and self-serving. It makes God an icon, a tribal God whose concerns are no bigger than our own…

Then we make ourselves God and our God a poor, miserable creature indeed—a national patriot, maybe; a great male warrior, perhaps, but certainly not the God of all creation. Then we are simply worshipping ourselves and calling it prayer.

(from Joan Chittister: Essential Writings, selected by Mary Lou Kownacki and Mary Hembrow Snyder (Orbis)).

Let us then not be like Pharaoh. Let us be like his daughter and the midwives. Let us develop great hearts and show them. Let us become Mahatmas in the image of God: in the image of Jesus Christ, the greater Moses, Amen.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed