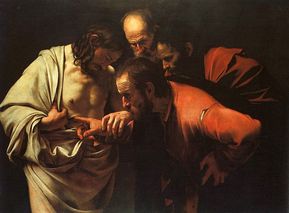

Caravaggio's 'The Incredulity of St Thomas'

Caravaggio's 'The Incredulity of St Thomas'  Amputee Christ - Cambodia

Amputee Christ - Cambodia Now, perhaps you’ll surprise me, but I suspect that few of us have heard a huge number of sermons on God’s love of the body, at least beyond MCC gatherings. Am I right? The body in much received Christian thought is often regarded with suspicion, even outright despising and repression. I don’t mean just LGBTI+ bodies either. Our particular bodies have come in for especially heavy attack and rejection. I suspect that is partly because we are typically more likely to affirm aspects of our bodies than others do. Indeed, just by existing, LGBTI+ bodies remind everyone of the human body as an entity, whereas much of Western thinking has tried to forget the body, or at least sideline it. Plato, the great father of most Western philosophy put it starkly: ‘the body’, he said, ‘is the prison house of the soul.’ Our job, he thought, is therefore to escape, or rise above, the body. Little wonder that so much of Western culture, including the traditionally dominant Christian religion, has similarly tried to escape, or at least chain up and control, the body. For bodies are notoriously tricky things, aren't they? They have all the kinds of things that Plato and the great Western ‘masters’ despised. They are full of imperfections. They change over time and eventually lose vitality. They come in all shapes and sizes, and, worst of all, they are never completely able to be controlled. Not only disease, decay and death affect them, but also longing, desire, and the strivings of the heart and soul. Frankly, according to much received Western ‘wisdom’, bodies are best hidden or ignored. No wonder, growing up with such surrounding preconceptions, that Christianity has often made such a hash of its own thinking and treatment of the body. There are important distinctions to be made between the body and the flesh but they are often passed over.

This all a bit strange if we spend time reflecting on the Gospels. For one of the queer (and I use that word advisedly) things about the Gospels – indeed perhaps the queerest thing about the Gospels - is that bodies are very, very, very central to the life, death and resurrection of Jesus. Almost wherever you look in the Gospels something queer is happening with bodies. If its not a virgin birth, then its a healing. If its not a body brought back to life, then its ears and eyes opened, the dumb speaking, the lame walking. If its not eating and drinking, wining and dining, then its feet being washed, hair sensuously draped over flesh, and all kinds of perfumes and oils lavishly employed. And almost all these bodies are marginalised, indeed often very queer, people. For God in Jesus seems to have a particular care for these kinds of bodies. Indeed, Jesus makes special, favoured, mention of the bodies of the poor and marginalised: not least the bodies of children, women, and eunuchs.

No wonder the poor old Australian Christian Lobby, and its right-wing allies, become quite so worked up about LGBTI+ people and so-called ‘progressive’ Christianity. They, like dear old Plato, and most of the old-style Christian ‘Fathers’, are still trying to fend off the body. The trouble is, the body is at the heart of Christian Faith. As many of us know all too well, to our own cost, when we have tried to fight it, the body just won’t go away. Nor should it. For, whilst it can be a mighty great challenge at times, the body, in Gospel understanding, is the place of grace. Indeed, above all, it is intimately connected with resurrection. Which brings us to our dear friend and apostle Bodily Thomas.

Bodily Thomas and Probing bodies

For Bodily Thomas had a problem, didn’t he? He’d heard the news about the Resurrection of Jesus but he just couldn’t bring himself to accept it without hardline proof. In this, Thomas the Body shows himself to be so much of a fundamentalist than anything else. The mystery of Faith wasn’t really his strong point. Never mind the spirit. Literally speaking it all had to be nailed down. He certainly could not make helpful distinctions between flesh and body. Hence we have the encounter with Jesus we hear tonight.

Now, I don’t know about you, but this conversation has a very familiar kind of ring to it for a transgender person. Father Shannon T. Kearns from Queer Theology in the USA put it very well recently. As a trans man, he said, he has lost track of the number of conversations he has had with nice enough people who somehow just have to have the details about his body. Yes, they say, I’ve heard you’re transgender but can I just get a few more details to satisfy my curiosity, my ‘need’, to reassure me? I know it is intrusive but, hey, you don't expect me to receive you just like that, do you? How about you tell me about all the wounds you’ve had to your body? Better still, how about you show me some of the scars? Maybe I can have a sneak peek, or a little investigation? I’m Thomas the Body, don’t you know, and I need to check out these things.

Now that kind of encounter is pretty exasperating really – or at least that is the polite way of putting it. It happens quite a good deal of course. Officialdom too is full of it. You’re transgender? Prove it. You want to change your birth name and assigned gender? Prove it. Prove to us that its not a lie. Prove it to us with your body. Prove to us that you’ve been through all we expect, or insist, you’ve been through. Prove to us that a doctor has checked you out: and a psychologist, and psychiatrists, and Uncle Tom Cobley and all. Prove it. Show us your scars. Let us touch your wounds. Prove to us you are who you say you are!

Do we see? Bodily Thomas isn’t the only one, is he? He just doesn’t trust what’s going on and the reality that is a transfigured body…

In response, Jesus was so very tolerant, wasn’t he? He agreed to Bodily Thomas’ request. Yes, he would show Thomas his body, his scars, his wounds. I guess, like many transgender people, he sighed a deep sigh and reckoned it was needed on this occasion. Poor old Thomas – stuck in the body. Unable to trust. Had to make his own investigation and probe Jesus’ wounds until he was satisfied. There are a lot of people like that, aren’t there? People who won’t believe, who won’t trust when the truth is told them. To paraphrase Jesus, blessed indeed are those who don't have to probe our transformed bodies. For that is the point, you see: Bodily Thomas and those like him don’t trust the resurrection of the body.

The resurrection of the body

It is all upside down, you see. In today’s world, this story about Thomas seems to be more reasonable. Indeed, of all the disciples, Thomas the Body appears to have some modern 'common sense'. After all, we‘re brought up in a so-called scientific age, believing something called ‘facts’ can be easily found and proved, and that they can some how solve all our problems and questions. It also seems difficult today for many people to believe that what has died can be transformed by resurrection. But that was not such a problem to the ancient world. The issue people had back then was essentially the opposite: they had little problem with various forms of eternal life, but they simply could not see how bodies, material existence, had any real or lasting point.

Bodily Thomas’ story is therefore a shocker for the ancient world and to ours, but in different ways. It reaffirmed to the people of Jesus’ day that God was truly concerned with our bodily, material, existence. The Way of Jesus in that respect is not about escaping from the world and our bodies, but about being transformed with them. It is funny really. Today many people have issues with Christian doctrines such as the Virgin Birth and the Resurrection. They can seem too other-worldly. In Jesus’ day however they represented the opposite. They appeared too worldly, too materialistic, too much about bodies. The idea that God becomes flesh, becomes material, becomes a body, was deeply offensive. That the resurrected also had bodies was also an extraordinary idea. It was a bit like a lovely woman I knew in Toowoomba who complained that we had used the ancient Apostles Creed in a service instead of the ancient Nicene Creed with which she was more familiar. When pressed about what she most objected about the Apostles Creed, she said that it was because it spoke of ‘the resurrection of the body’ not the ‘resurrection of the dead’. ‘The resurrection of the dead’ she could imagine, she said. It might take a variety of spiritual forms. Let’s however leave our bodies behind.

Is that how we imagine resurrection? Our Gospel story suggests something quite different. Of course, the resurrection body is very distinct from the bodies we know. St Paul talks about that in 1 Corinthians 15 where he suggests that the bodies which die are like seeds. The resurrected body is something much more and impossible for us to imagine. For, as he wrote, ‘our bodies are buried in brokenness, but they will be raised in glory. They are buried in weakness, but they will be raised in strength.’ And yet those bodies are also inextricably linked with our current bodies. There is profound change, but also intimate continuity. That is what we see in the resurrection body of Jesus, don’t we? This is a body quite different and unimagineable to us: it can seemingly appear at random, behind locked doors, and is no longer bound by the powers of suffering and death. Yet it is also immediately recognisable and physical enough to be visible and able to be touched.

Revaluing broken bodies as blessed

This bodily continuity is very important for us: not just to assure us of the possibilities of our own resurrection by God’s grace but also in reminding us of the kinds of bodies which God loves and transforms. For, if Thomas the Body was a bit of a clumsy fundamentalist, seeking nailed down truth, his story also helps us affirm the value and potential transfiguration of our bodily selves. Let me briefly offer three examples of this: three modern instances of resurrection grace in broken, yet blessed, bodies. I’m sure that Bodily Thomas would appreciate them all!

Nancy Eiseland and the 'disabled God'

The first example is Nancy Eiseland, a remarkable pioneer theologian of disability. She died at the age of 44 in 2009, after having lived with pain throughout her life due to a congenital bone defect in her hips, for which she had 11 operations before the age of 13. With all of that, why do you think she said that when she went to heaven she hoped she would still be disabled? I don’t think it was because of the pain! Her reason was that her identity had been formed with her disability, so that, without it, as she put it, she would ‘be absolutely unknown to myself and perhaps to God.’ In that sense, Nancy might have agreed that Bodily Thomas did us a good turn in confirming that Jesus still bore the wounds and brokenness of his body. As Nancy reflected about Luke chapter 24 verses 36-39, where Jesus invites the disciples as a whole to touch him as they look as if they seen a ghost:

‘In presenting his impaired body to his startled friends, the resurrected Jesus is revealed as the disabled God.”

God thus remains a God the disabled can identify with, Nancy argued: he is not, in that sense, cured and made whole; his injury is part of him, neither a divine punishment nor an opportunity for healing.

With all our variety of bodies, does that make sense to you, or to someone you love? It does to me. It affirms that God is the God of all of us, whatever our bodies are like, positive or negative. For even the negative aspects of the body of Jesus the Christ are taken up into the fullness of God in the Resurrection. It is the Differently Abled Christ who is resurrected for us. Through his life, death and resurrection, all that is valuable about all our bodies is raised.

The Amputee Christ of Cambodia

The second example of resurrection grace in broken, yet blessed, bodies, comes from the church in Cambodia. It is a message of resurrection hope in the face of the terrible destruction of so many lives in the past. For a powerful image which has arisen from the Cambodian context is that of the Amputee Christ. It emerged from the horrendous damage that was caused by landmines, with so many people losing limbs. Like the cross of Christ, those horrendous wounds are witness to the sin and violence of our lives and world. Yet, like the resurrected body of Christ, those same scars are sources of love, re-connection, and a kind of resurrection for many. Some of you may recall me speaking about the meaning of the Cross a few weeks ago and some different symbolic varieties of it. For me, the cross of the Amputee Christ is perhaps the most poignant, yet also hopeful, in our modern world. Like the wounds of the Differently Abled Christ touched by Bodily Thomas, they are both a reminder of the reality of our past and the promise of its transformation and fulfilment. Through such wounds, God brings healing.

Rachael Mann, Dazzling Darkness and the healing wounds of Christ

My final example of resurrection grace in broken, yet blessed, bodies comes Rachael Mann, a fellow Anglican priest and transgender woman in England. Rachael is a remarkable person on so many levels, not least as a poet and writer. I commend her book Dazzling Darkness to you. It tells something of her personal story and wrestles with what it means to speak of God in the face of darkness. This includes not only the struggles she had to realise her gender identity but the awful pain she has periodically endured from chronic illness. Like Nancy Eiseland and the Cambodian Church, this is the kind of experience to make us doubt God and wonder about the reality of the risen Christ. However, like Nancy and the Cambodian Church, Rachael points us back to the truths revealed by the blundering Bodily Thomas. Are we to reject the body, or expect that it will disappear in eternal life? No, says Rachael. Instead, she urges:

“Give me bodies - wobbling, wrinkly, stretched-marked, even surgically enhanced bodies. Bodies enjoying themselves. Bodies unfrightened of their possibilities. God has no fear of bodies. This is the truth at the heart of the incarnated God. The idea of God emptying him- or herself into fragile flesh is one of the great shocks of Christian theology.”

As I say, Rachael is not proclaiming this from an easy place. She knows that the resurrection and the cross are inseparably linked. Yet, like Bodily Thomas she has come to an awareness that it is through the transfigured body of the Differently Abled Christ that true healing and hope comes.

Let me leave you with some more words of hers, which express something of what it is to experience and live the resurrection right here and now. This is what Thomas the Body no doubt discovered as he passed his hands through the pain of Jesus into the promise of the Differently Abled resurrected Christ: the discovery that it is through our bodily wounds that God’s grace works, transforming us bit by bit in this life, and a whole lot more beyond, into the glorious body of Christ. For Rachael’s own journey, as she puts it, through:

‘bouts of wild living, endless self-indulgence, a sex change, questions about my sexuality, and nasty, nasty chronic illness – has been nothing more or less than an adventure in becoming more myself in the wholeness that is God. It has been, and is, an adventure into places of both joy and considerable pain. It is a journey down into being – into being me by being in God. It is a mystery of connection – the more I know God, the more I know me and the more I know me, the more I know God. It is also a journey into a kind of terror… discovering that somehow … in my messy brokenness… I am most me. It is into this place that Christ comes, the Christ whose wounds never heal, though she be risen; the Christ – the God – who holds the wound of love within her very being. For, so often, it is our very woundedness, our vulnerability, which feeds and heals us.’

In the Name, and through the grace, in the wounds, of Jesus, Amen.

Jo Inkpin, for Metropolitan Community Church Brisbane, Easter 2 Year B, Sunday 8 April 2018

RSS Feed

RSS Feed