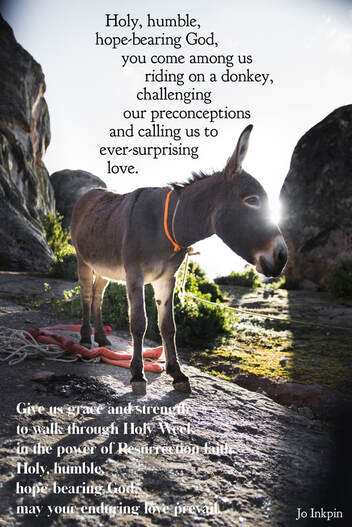

prayer by Jo Inkpin; Unsplash photo

prayer by Jo Inkpin; Unsplash photo One of my daughters asked me this, shortly after our Earthweb-led involvement in the recent ‘Sound the Alarm’ Green Faith events, followed shortly by the presence of some of us on the March4Justice and planning for today’s Palm Sunday Refugee rally. I had to be honest: ‘well’, I said, ‘pretty much every week we, or some of us at least, are involved in something.’

And why wouldn’t we be?

Today’s Gospel reading after all (Mark 11.1-10) is a reminder of what I would call the ‘prophetic performance art’ which reappears again and again in the Biblical stories. The so-called ‘entry into Jerusalem’ by Jesus is but one example of this - admittedly particularly significant. For it does not stand alone, nor was it originally intended to be simply repeated or venerated. Rather, in embodying Jesus’ own call to transformation, it seeks to inspire us to our own prophetic performance art. In this we are not exactly social influencers like today’s social media stars, but we are like divine influencers in reshaping our world. All of which can sound, or become, quite pretentious. So maybe a better, arguably more biblical, way of putting it is that we are called to become the wonky donkey…

For I do not mean to sound sacrilegious, but – if we look at the story of the ‘entry into Jerusalem’ again - we may see that today’s Gospel events were meant to be hilarious, just like the wonky donkey at its centre. After all, never having been ridden before, the donkey must have been quite a sight - intentionally. For this was a deliberate huge send-up of the power, pomposities and pretensions of the ruling establishments of Jesus’ day. It took key features of this and not only mimicked and subverted them, but did so in ways which would have been screamingly funny as well as startling. Let’s think, just for a moment, about that donkey (or mule, or possibly a very young colt) at the centre. Jesus chooses to ride this animal, rather than the powerful beautiful war-horses which Roman and other leaders, would ride into their major cities as symbols of their power and victories. Today it is usually powerful jets and limousines, often surrounded by tanks, airplanes flying past, many gun salutes, and even soldiers goose-stepping. That can look impressive of course – that is the aim. Yet is it really? Jesus was asking the question and sending it up. Instead of tanks and airplanes, we have palm leaves torn from nearby trees. Instead of many gun salutes and soldiers goose-stepping, we have a few ordinary cloaks. Instead of jets and limousines, we have a humble donkey. What kind of vision of power is this?

renewing prophetic laughter

Jesus was also conscious of biblical prophecy, which talked about a Messiah, a kind of saviour-king, riding on a colt or donkey. In acting as he did, Jesus was thus also provoking hilarity towards the pretensions of the religious establishment, who claimed to know the scriptures. The onlookers of this action would have seen it immediately as what it was – a carefully constructed charade to ridicule and puncture the hold of the powerful over others. For as others have discovered down the centuries, from ancient satirists to modern comedians, one of the best ways to defuse fear of the powerful is to poke fun at them and make them and their claims seem ridiculous – which, actually, is what most claims to authority over others actually are. Make someone laugh and we open up fresh possibilities: new ways of seeing and behaving.

This is indeed performance art - prophetic performance art, when drawn, as by Jesus, out of the biblical tradition. What better way to express this divine mimicry too than through a donkey. As I say, note well, Mark’s Gospel tells us that it was not just a donkey, but one that had never been ridden. So what we have is Jesus on a very unstable animal – truly wonky! Imagine how Jesus and the donkey would have staggered into view, wobbled about, made such a performance!

eco-performance art

Viewing this with contemporary eyes, Jesus is also here making a radical identification with the rest of Creation, and the Spirit within it. Draped in palms and cloths, Jesus and donkey appear here as a kind of amalgam of human, other animal, and vegetation. Like the archetypal Green Man, found in so many cultures, and some Christian churches, the palm-donkey-Jesus creature represents rebirth, through a renewing of relationship between all created aspects of the Earth.

This is also no romantic ecological fantasy, but one clearly here connected with powerful struggles of the economy and environment in which Jesus lived. Some scholars have rightly pointed out that, in this prophetic performance art protest, we see the expression of the poor. It was a more than welcome ridicule on their behalf for the peasant farmers, fisherfolk and other workers whose livelihoods were being impoverished and marginalised. Jesus’ followers would have eagerly cooperated, and laughed with liberation, at how the elements which shaped their own lives were used to turn the tables on the rich and powerful.

what was Jesus' plan?

Again, this was hardly a spontaneous event. The biblical text itself suggests it was deliberately and carefully planned. Which raises a significant question, which scholars have often struggled to answer, or simply by-passed. Why does the story end in an anti-climax, with Jesus simply dispersing the crowd, and heading back out of Jerusalem to Bethany? For the triumphal entries of the powerful which Jesus was ridiculing ended in lavish and symbolic events, including great feasting. Why then did Jesus not push on to such other things?

Answering the question of why this entry story ends in anti-climax takes us to the heart of the Jesus strategy for divine transformation of our lives and world. This, as symbolised in the wonky donkey, involves a radical revolution in how we view and use power. And this is simply not what people then expected, or what our own world still expects.

Among recent scholars, the Korean-Filipino theologian Dong Hyeon Jeong is one who offers us illuminating fresh insights n this story. Three in particular resonate with me.

Jesus' Flash Mob

Firstly, Dong Hyeob Jeong helpfully suggests the phenomenon of the Flash Mob as a modern analogy for what Jesus and his disciples were doing with the donkey.. You know the kind of thing - a small group will suddenly form, seemingly spontaneously, but actually with sharp attention to place, timing, and publicity. In the midst of a large crowd they will then draw others’ attention - maybe with action, music and singing - perhaps adding to their numbers as some onlookers join in. Then the flash mob disperses as quickly as it formed.

Some of the performance art of The Chaser has been like this, stirring up aspects of Sydney and wider Australian life. Similarly our Earthweb ‘Sound the Alarm’ event had such features, including our flash mob who suddenly entered Pitt Street Mall, grabbing attention from the crowds of shoppers, not least with the bagpipes. In this we were part of Jesus’ flash mob for today.

the 'queer art of failure'

Secondly, Dong Hyeon Jeong helpfully likens Jesus’ strategy here to what the queer theorist Jack Halberstam, also known as Judith, calls ‘the queer art of failure’. Now we could explore how Jesus ‘queers’ life and religion in all kinds of ways - and I hope, in times to come, we will. ‘Queer’ is of course a modern term, and linked to sexually and gender diverse people in particular. Yet, as Halberstam uses it, it also represents approaches that all kinds of people use when they represent something beyond the assumed norms and ‘order’ of society. For in order to subvert oppressive realities, artists of all kinds, ‘queer’ the world. This involves challenging suppression by finding creative ways of breaking up ‘normal’ ways of seeing and doing, and offering up new ways of being - just like Jesus, and their flash mob, in our Gospel today.

Typically such approaches also subverts neat categories - just as Jesus does so, including in today’s Gospel, so- called fixed boundaries of sacred and profane, human and animal, and human and divine. Some of these pathways might be surprising, even shocking, and foolish, and they may be ephemeral. However, even in their apparent ‘failure’, they change things - just as Jesus changes things, in all the seeming events of Holy Week which at the time seemed like failures- not least the Cross.

For Jesus’ queer art of failure is Good News. This is the living Gospel. it offers empowerment for those who fail norms and may never succeed. It is a pathway to give new value to ourselves and for the utterly neglected - that is, all the donkeys, who are, as Chesterton put in his poem: ‘the tattered outlaw of the earth’.

a 'third way'

Thirdly, and finally for now, Jesus’ ‘queer art of failure’ is intimately linked to what modern thinkers have also termed a ‘molecular revolution’ approach to change. This is about finding ways not merely to challenge unjust power and unnecessary pain, but to do so without replacing them with new forms of oppression, and, crucially, without reliance on key leaders who may be killed or otherwise suppressed in the process. For what Jesus offers is a ‘third way’.

The idea of a ‘third way’ for people to transform oppression and find authentic life is also of a modern concept but with ancient foundations. Today it is found notably in the work of the great Indian theorist Homi Bhahba, and has been influential in recent anti-colonialist and post-colonialist thinking. Yet, as we see in today’s Gospel, it is nothing new. As part of the or own Judaean anti-colonialist struggles, Jesus subverts the established ruling categories, mimicking them and creating new hybrids. Compared to traditional ideas of power, Jesus’ entry into Jerusalem is thus, to use words of Homi Bhabha, ‘almost the same but not quite’ - and in this difference lies the pathway to true transformation of both religion and politics.

Sadly, the history of Christianity is so often the story of re-imposing traditional ideas of power on Jesus’ way of liberation. Instead of subversion, as in today’s Gospel, it becomes a means of repression. Where Jesus, for example, was sending up the pretensions of ‘normal’ ideas of kingship, Christians have often made Jesus into a king with all the usual trappings.

Our challenge is therefore to recover the dynamism of Jesus. For Jesus’ approach was not to centre everything on themself, still less create an ideology, political or religious. Rather Jesus invites us to share in their, divine, way of transformation. This is not revolution from above, or even below, but mutual prayer and action that subverts the very idea of revolution itself.

Christians trying to create a new godly empire was never a good idea. Our world certainly no longer needs that today. Yet it badly needs transformation. As Christians we are therefore still called to be flash mobs. We may be small and seemingly powerless, but we can be truly subversive, especially where we engage in imaginative fun, not seeking worldly ‘success’ but trusting in the ultimate triumph of God’s transforming love.

To put it succinctly - let’s face it - the story of the first Palm Sunday vividly proclaims Jesus as a stirrer. So too we are called, for the sake of divine love, to be stirrers, even as the wonky donkeys we may know ourselves to be. So, see you at the next prophetic performance art event, with the spirit of Jesus’ divine laughter. Amen.

by Josephine Inkpin, for Palm Sunday 28 March 2021, at Pitt Street Uniting Church Sydney

some source references for further reflection:

Gospel of Mark, chapter 11.1-11

The Donkey, by G.K. Chesterton - https://www.poetryfoundation.org/poems/47918/the-donkey

Jesus’ “Triumphal Entry” as Flash Mob Event: molecular “r” evolution in Mark 11.1-11, by Dong Hyeon Jeong

- https://cpb-ap-se2.wpmucdn.com/blogs.auckland.ac.nz/dist/f/375/files/2019/12/Dong-Hyeon-Jeong-article-FINAL.pdf

The Queer Art of Failure, by Halberstam, Jack/Judith. 2011. Durham, NC: Duke University Press.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed