Desire: that is not often a spiritual theme which is often affirmed in much Christian teaching, is it? Where desire is mentioned, it is often negatively, in terms of temptation, sin, shame and guilt. In particular, when desire is mentioned, many people think at once of either sexual desire or material wants, both of which are natural and healthy but which have been closely associated with condemnation in religious circles. Yet desire is so much more than this. Desire is key to being human, and, even more so, desire is vital to growing in holiness, into sharing divine life. This is at the heart of the story of Jesus and the woman at the well.

Scholars essentially agree that the story of the woman at the well is modeled on a standard betrothal ‘type scene’. This offers us various pathways of interpretation to explore. Not for nothing for example does this Gospel encounter occur at Jacob’s Well, a reminder of the great patriarch Jacob, of Jacob’s own extraordinary betrothals, marriages, and place in biblical salvation history. This brings a note of continuity, of recapitulation and of fulfilment to the Jesus narrative. Yet there are also significant differences between the Gospel story of John chapter 4 and Hebrew betrothal type-scenes. Among these are that the woman is not Judaean but Samaritan. She is not a virgin but a woman with considerable sexual experience and maturity. There is no actual betrothal. The well is not essentially related to sexual fertility but is an image of salvation. Meanwhile Jesus is not primarily presented as a bridegroom but as a giver of living water.

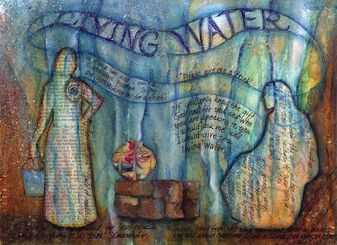

I would encourage us to hold these aspects of today’s Gospel story in creative tension. Indeed, like other great biblical stories, we might profitably view it as an imaginative icon, and let its various lights and parts speak to us. What words, images, and themes speak most powerfully to you, today? Do you see meaning, for instance, in the powerful transformations of some of the imagery of last week’s Gospel story of Nicodemus? In John chapter 3, a significant and honoured man of the establishment comes to Jesus for guidance in the darkness of the night. Here, in John chapter 4, it is an outcast and disreputable woman who challenges Jesus, at high noon, in the heat of the day. One seeks light and wisdom, the other water and renewal. On another occasion, we could also certainly explore further the significance of the woman being from Samaria, the despised ‘other’ cultural and religious complement of Judaea. For there are important racial and other power resonances at play here. The sexual aspects of this are indeed also strong and invite us to further reflection on the sexual dynamics and gendered imaging of woman and men in scriptural tradition, not least in Hosea. Let me however come back to desire, which I feel is at the very heart of this story, and which is so easily overlooked.

all desires

Now, as I said earlier, I mean by desire much more than sexual and material wants, though these should hardly be passed over in this story. We should not, for example, dodge the likely issues of poverty and oppression surrounding the Samaritan woman. More than likely she lives life hand to mouth, clearly without settled family arrangements or security. Jesus indeed says she has a partner, but it is not her husband and she has had five of those. Is that because of death and other disaster, or violence and abuse? We do not know but we can imagine. Her presence at the well, and her willingness to talk to a strange man, certainly suggests she may be desperate for help, if only for vital financial support from sharing herself with another. In that, I am personally quite taken with my wife Penny’s ‘R rated’ take on this story,[3] which she sees as John’s Gospel’s version of the Temptations narratives in the Synoptic Gospels, but - with all that flirtatious talk of wells, shafts and digging - full of sexual innuendo. Yet there is still more.

Let me come back to Janet Morley and All Desires Known. That title for her beautiful compilation of feminist prayers was deliberately chosen by Janet, as a good Anglican – albeit one who worked for many years for both the Methodist Church and Christian Aid. For the phrase comes from one of the most famous prayers of Thomas Cranmer, known as the Collect for Purity, itself translated from an 11th century prayer written in Latin. Used at the beginning of worship, not least for centuries through the Book of Common Prayer, it has been powerfully influential across the globe. For those with no Anglican heritage, it goes like this:

Almighty God, unto whom all hearts be open, all desires known, and from whom no secrets are hid, cleanse the thoughts of our hearts by the inspiration of the Holy Spirit, that we may perfectly love thee, and worthily magnify thy Holy Name: through Christ our Lord, Amen.

Janet Morley’s take on this is as follows (from her preface to All Desires Known):

‘All desires known’: this phrase evokes in me that distinctive stance which I associate with authentic worship: namely an appalled sense of self-exposure combined with a curious but profound relief, and so to write under this title has been both a discipline and a comfort. I have chosen it because I understand the Christian life to be about the integration of desire: our personal desire, our political vision, and our longing for God. So far from being separate or in competition with one another, I believe that our deepest desires ultimately spring from the same source; and worship is the place where this can be acknowledged.

living water

Integrating our desire – our personal desire, our political vision, and our longing for God – that, in a nutshell, is what Janet Morley saw as the purpose of worship, as a space where Christ is encountered. Is this not also the unifying heart of our Gospel story today? For in the story of the woman at the well, we find her, and Jesus, exposed: their desires breathing so heavily in the heat of the day. These include all manner of desires: desires for verbal, physical and spiritual contact and communion; desires for relief from struggles of all kinds, including bodily and spiritual wounds, poverty, racism, sexism, exclusion and oppression; desires for deep down, ultimate, healing, renewal and lasting peace – in body, mind and soul; desires for living water for an eternal thirst.

The good news of today’s story, and all our stories, is that our desires, our thirsts, can find their living water. That is the heart of the Christ experience – for the woman at the well, and for all those whose hearts are open. For, as the woman discovered, our saving truth is the truth of the Collect for Purity: that all our desires are already known to God, all hearts are open, and no secrets are hid. Coming in prayer to God may indeed, as Janet Morley put it, often involve us in a deep sense of self-exposure. Yet, like the woman at the well, when we truly open our hearts and acknowledge our hearts’ desires, we find profound relief.

wells

Macrina Wiederkehr puts it this way, in the contemporary reading we heard read earlier this morning:[4] ‘what makes this world so lovely is that somewhere it hides a well.’ She is right, isn’t she? That is the witness of Jesus and the woman at the well. Sometimes, as Macrina says in her poem, people are like wells. Like Jesus for the woman, we meet Christ in them, where they are:

deep and real

natural (un-piped)

life-giving,

calm and cool,

refreshing.

They bring out what is best in you

They are like fountains of pure joy

They make you want to sing or maybe, dance.

They encourage you to laugh

even, when things get rough.

And maybe that’s why

things never stay rough

once you’ve found a well.

Macrina goes on to say that some experiences, like that of the woman at the well, can also be like wells for us. This is part of the invitation to us. Indeed, one of the aspects of today’s Gospel story which is often passed over is that not only that the disciples shocked to find Jesus speaking with a woman - and that kind of a woman – but that the woman, that woman, went on to share her experience and to be a well of living water for others. In effect she became the first female evangelist, or the first living well - which is probably a healthier, more evocative and spiritually refreshing, name for an evangelist, a sharer of good news, living water.

When this faith community was seeking a new Minister, it described itself as seeking to be ‘a well, and not a well-oiled machine’. That captivated me, as it should captivate us all. For each of us, and together, are called to be and create wells, and not so much well-oiled machines – though they can be kinda handy at times! How are we going with that? Our Gospel story today recalls us to that. For, as Macrina Wiederkehr encourages us, when we open our hearts, there are wells of living water:

Wells of wonder,

Wells of hope.

When you find a well

and, you will some day,

Drink deeply of the gift within.

And then, maybe soon

you’ll discover

that you’ve become

what you’ve received,

And then you will be a well

for others to find.

In the name of God, the source of living water, in whom all desires are known. Amen.

by Josephine Inkpin, for Pitt Street Uniting Church, Sunday 12 March 2023

[1] Fageol, Suzanne (1991). "Celebrating Experience". in The St Hilda Community (ed.). Women Included: A Book of Services and Prayers. SPCK. pp. 16–26

[2] Furlong, Monica (1991). "Introduction: A 'Non-Sexist' Community". in The St Hilda Community (ed.). Women Included: A Book of Services and Prayers. SPCK. pp. 5–15

[3] https://www.penandinkreflections.org/blog/touching-places-and-entry-ways

[4] See https://www.jamberooabbey.org.au/3rd-sunday-of-lent-woman-at-the-well/

RSS Feed

RSS Feed